Two sailors have done it before him

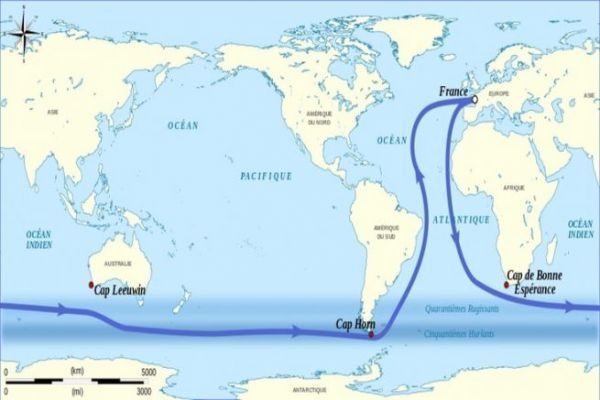

On January 9, 2000, a few days after the famous bug that never happened, Philippe Monnet set sail from Brest in an attempt to beat the round-the-world record, held by Englishman Mike Golding in 161 days. In contrast to the route taken by the Vendée Globe skippers, Philippe Monnet will be sailing from west to east, against the prevailing winds and currents. Two British sailors have successfully completed this demanding course: Chay Blyth in 1970, then Mike Golding in 1994.

In order to shorten the distance, Monnet's strategy was to descend far to the south, beyond the Antarctic Circle, where very few boats have ever ventured, let alone a single-handed 60-footer.

An invigorating but rapid descent of the Atlantic

With Oliver de Kersauson and Florence Arthaud cheering him on, Philippe Monnet crossed the starting line between Ushant and Lizard Point. For this adventure, he has chosen to set off aboard Uunet, a Briand design that he has completely rebuilt and prepared for the specificities of this course. As most of the course will be sailed upwind in heavy weather, he opted for a narrower hull than the other 60-footers, which are typically downwind boats. What's more, her Kevlar construction on a carbon structure is less resonant upwind than an all-carbon hull.

The descent of the Atlantic was punctuated by several large depressions, causing minor damage to the sails. The battery pack also malfunctioned, but Unnet, who has a reputation for being a good walker, was able to achieve good averages. Off the coast of Chile, a huge wave causes the skipper to take off while tinkering inside, landing him on the chart table, breaking one of his computers and the Standard C communication system. Philippe crossed the equator on January 26, 2000, 5 days ahead of Mike Golding, and rounded Cape Horn on February 16, after 39 days at sea.

A testing Grand Sud

Once the "Cap dur" had been left to starboard, Monnet entered the Deep South, knowing that he would be sailing close-hauled for two months in heavy weather and ice. The Pacific welcomed the skipper with 50-knot gusts, and temperatures dropped rapidly. The sky and sea turn gray. The stage is set.

Both the boat and the skipper suffer in these trying sailing conditions. A frame broke in the forepeak, forcing Monnet to straighten it.

The air temperature is negative and the water temperature around zero degrees. On February 22, Uunet crossed its first iceberg. Life on board is complicated, especially as the oil-fired heating system has broken down. Everything is cold and damp.

At 65 degrees south, with snow and fog, visibility was zero. The skipper slaloms between icebergs and growlers, his eye riveted to his radar. Conditions are appalling, and the wind rarely drops below 35 knots. After each maneuver, Monnet dips his fingers into the pressure cooker to try to warm them up. He lives holed up like an animal, sleeping in oilskins and boots, with the constant fear of hitting a growler, which the radar is unable to detect.

On February 26, he faced 80-knot winds on dry canvas. But this was only the beginning. His router, Pierre Lasnier, announces the arrival of three hurricanes, generating gusts close to 100 knots.

The portholes froze and a layer of ice formed on the mast and shrouds, which Philippe had to break off regularly to keep the boat's balance.

At the beginning of March, the bracket securing the starboard runner showed signs of weakness. If it failed, the mast would fall. The skipper headed north to find better conditions. At 54 degrees south, he was hit by cyclone Leo, with winds of 60 knots.

After 1 month in these appalling conditions, Monnet is still 4 days ahead of Mike Golding's record. The sun reappeared on March 17. The hell of the deep south is over.

An Indian Ocean full of surprises

On March 27, Uunet left the South Pacific and entered the Indian Ocean. Temperatures are rising and the risk of collision with ice is over. But the wind remains strong. Under 3 reefs and staysail, the boat trims her course. It was then that Philippe fell victim to an attack of malaria in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Amorphous and untreated, he spent three days at the bottom of his bunk with a high fever.

On April 4, the winds became downwind and Monnet hoisted his gennaker and rediscovered the pleasures of gliding. The skipper revitalized and cleaned up his boat. The technical assessment is rather good, and the delamination of the starboard runner has stabilized.

Uunet's days are 250 miles long. The record and the pleasure of sailing are back on track.

On April 25, the on-board equipment flickered. There's a problem with the on-board power supply, and the skipper heads for the aft forepeak, where the batteries that have caused problems in the past are connected. As soon as the door is opened, thick smoke emerges. The park is on fire, due to short-circuited cables. Monnet pulls them apart with his bare hands, severely burning both hands. A shot with a fire extinguisher solves the problem.

Philippe switches his power supply to the tray preserved by the fire, and takes care of his hands.

A few days later, while sailing on the beam at 30 knots, he encountered an underwater volcanic eruption. The phenomenon, which is extremely rare, is reflected on the surface by violent thunderstorms, lots of lightning and oppressive static electricity.

Off the Mozambique Channel, a very strong low-pressure system forced the skipper to use trawlers to slow down Uunet, which was out of canvas. The movements were so violent that the skipper took off in a wave and landed on his titanium steering wheel, which shattered on impact.

As they approached Bonne Espérance, the seas were very rough, and Mike Golding's lead over the record melted like snow in the sun. Uunet returns to the Atlantic Ocean 5 and a half days ahead.

An Atlantic express

The climb back up the Atlantic will take place in much milder conditions than those encountered over the past two months. Despite a few lows, Monnet increased his lead. On June 9, he crossed the finish line in the Iroise Sea, welcomed by dozens of boats. After 5 months at sea, he beat Mike Golding's record by almost 10 days.

Icebergs, hurricanes, fire, malaria and underwater eruptions: nothing spared Philippe Monnet on this record, which he had to relinquish to Jean-Luc Van Den Heede in 2004.