Model basis for analysis

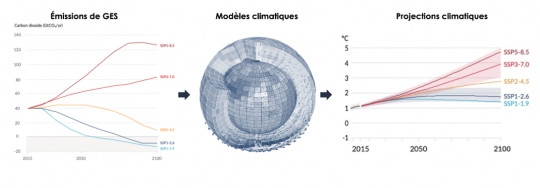

To get a glimpse of future weather patterns, Axa Climate scientists have modeled the planet's atmosphere as millions of tiny cubes interacting with each other.

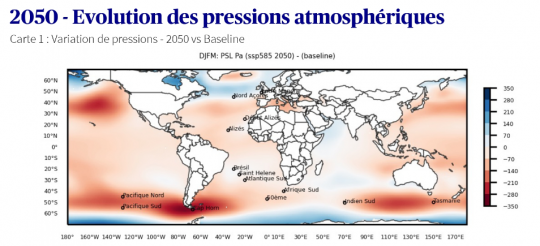

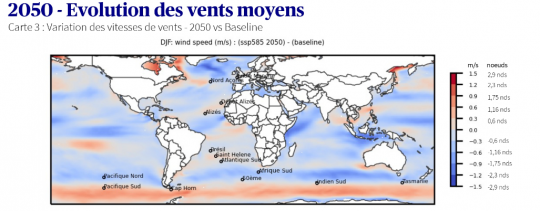

Based on the IPCC's SSP 5-8.5 scenario, considered the most likely, in which greenhouse gas emissions would continue to rise, they estimated how global weather would evolve by 2050. It should be noted that this is an average evolution for the months of December to March for 30 years centered on 2050, and compared to a baseline which is the average from 1985 to 2014.

What impact will a round-the-world trip have in 2050?

The results show slightly less powerful anticyclones, and slightly less hollow lows in the North Atlantic. On the other hand, lows in the Deep South, i.e. above 50 degrees South latitude, are set to strengthen.

This should logically reduce the average wind in the North Atlantic, shifting it a few degrees to the east. The doldrums could descend to the south of West Africa.

In the South Atlantic, above the 50th parallel, where the Vendée Globe skippers could be affected, the wind is expected to be slightly lighter, and more westerly. However, below the 50th parallel, average winds are expected to be 1 to 2 knots stronger and more southerly than at present. A more southerly wind is also more gusty, and less stable in direction. At these latitudes, the Jules Verne Trophy attempts in particular would suffer.

Beware of the reality behind the averages!

But don't be fooled into thinking that these rather alarmist results will only have an anecdotal impact on our next round-the-world races, since the simulations presented here are averages. Christian Dumard points out that these figures conceal a more complex reality. We have to expect much more violent phenomena (storms, cyclones, doldrums...) and not forget to take into account all the other factors that climate change will bring. For example, the migration of cetacean populations, which will force us to review our routes to avoid breeding grounds. We also expect to see more icebergs and growlers along the way, even if satellite images and detection equipment should make it easier to locate them.

What about the other scenarios?

All these data are based on the SSP5-8.5 scenario, a "business as usual" scenario which assumes that greenhouse gas emissions will continue to accumulate in the atmosphere, and that temperatures will rise by 2.5°C by 2050. Although this is the most likely scenario (according to the IPCC), other scenarios have been anticipated by the IPCC. Unfortunately, among the scenarios considered the most likely (SSP3 and SSP5), the consequences for the results presented are marginal (the scenarios diverge more markedly by 2100). We would have to turn to much more optimistic scenarios (SSP2 or even ideally SSP1), which would require radical changes if we were to hope to disprove these forecasts.

/

/