A first anthology edition

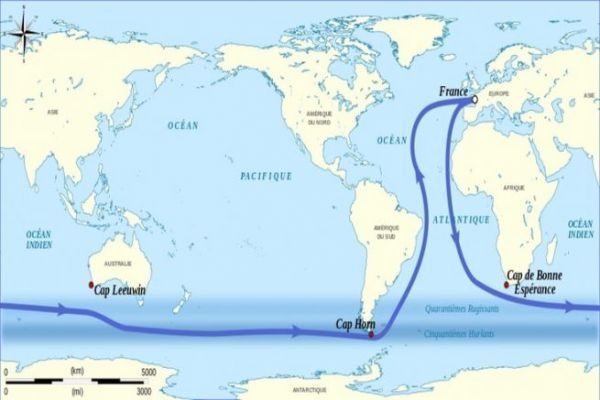

At the end of November 1989, 13 solo sailors set off on the first Vendée Globe, the first non-stop, unassisted, single-handed round-the-world race. And they're not messing around. Few sailors before them have ventured into these hostile seas. The fleet is fairly disparate, with a mix of new prototypes and old ocean-racing glories. Only the Cacharel, ex-Pen Duick 3 and skippered by Jean François Coste, is rightly judged to be strong enough to take on the southern seas.

Philippe Poupon is one of the favorites. The sailor has already won several Figaro races, the Route du Rhum and the English transatlantic race. His 60-footer, Fleury Michon X, is a brand-new Briand design equipped with the latest technology. At launch, the boat was rigged as a sloop. But judging the mainsail area too large, and especially the boom too long to cope with the southern seas, Poupon modified his rig and added a mizzen mast.

Loïck Peyron takes the start aboard Lada Poch, a Bouvet Petit design that has already won the Boc Challenge with Titouan Lamazou. Not as fast as the latest protos, it has undergone a major refit at Marc Pinta's facility in La Rochelle.

Lying on your side

Off South Africa, Titouan Lamazou is in the lead aboard Ecureuil Poitou Charentes II. Behind him, Philippe Poupon on Fleury Michon X attacks to try and catch up. On December 27, Race HQ received Philippe Poupon's distress beacon signal. At the time, communications were by radio. No one knew the nature of Poupon's distress.

Loïck Peyron is the nearest designer. Suffering from pilot problems, he didn't pick up the first message from Race HQ. It's at the 2 e lada Poch's skipper receives the request for assistance. The skipper from La Baule completes his repairs, then sets course for Fleury Michon's presumed position. He prepares a bunker in case Poupon needs to be taken on board. It took him 24 hours to reach the search zone, sailing close-hauled in steady conditions. In the storm, his rigging slackened. He has to climb the mast to repair it.

As he struggles in his mast chair, he spots the wing of a reconnaissance plane pointing him in the right direction. He reduced his mainsail to three reefs to limit his speed, and kept a small headsail to remain maneuverable.

That's when he discovered his friend's 60-footer lying on its side. Fleury Michon X was left lying on the surface of the water, like a simple dinghy. By his own admission, Loïck Peyron hadn't expected to see his friend in such an awkward position. " I was prepared for anything but this situation. I thought I'd find him overturned or in his raft. Dismasted, no, because Philou wouldn't have called for help and would have managed to reach dry land on his own " .

An epic rescue

Peyron makes a first pass and sees no one. He yells to signal his presence, and Poupon gets out of his boat in a survival suit. They communicate by VHF to take stock and agree on the next step.

Philippe Poupon gave himself a real fright. Lying on his side for over 24 hours, he tried to balance the 3500 liters of ballast in an attempt to right his boat, sometimes seeing himself sink to the bottom. A trailer will be brought in to help Fleury Michon X right herself. As a good communicator, Loïck films the maneuver with a camera fixed to the stern arch. He almost falls overboard as he picks up the line thrown by his unlucky rival.

After 20 minutes of towing to get back in line with the wind, the Briand plan failed to right itself. Exhausted, Peyron took a short nap. He was then awakened by Philippe Poupon, who announced that he was ready to cast off the mizzen. All the shrouds are cut, and the battered 60-footer finally straightens.

The mainsail was in tatters, the rigging was damaged, but Fleury Michon X was able to get back on course. After considering continuing the race for a while, Philippe Poupon resigned himself and headed for South Africa, where he announced his retirement.

At the time, it was impossible to send a video from a sailboat on the open sea. It wasn't until after rounding Cape Horn that Loïck dropped the tape in a watertight bag to his brother Stéphane, who had come to greet him from another yacht. Literally and figuratively, the images went around the world, helping to raise the profile of the race.

Loïck will finish 2 e after 110 days at sea.

/

/