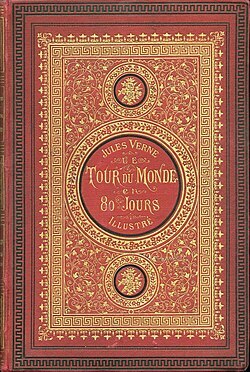

A challenge initiated by Jules Verne

In 1873, Jules Verne published one of his most famous novels, Around the World in Eighty Days. This classic novel features the eccentric British explorer Philéas Fogg, who bets with his club members to circumnavigate the globe in less than 80 days, whatever the means of locomotion.

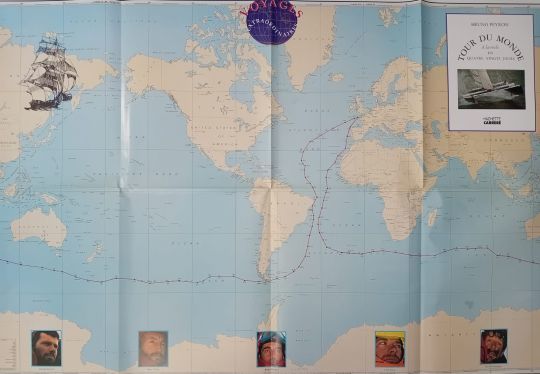

More than a century later, a group of sailor friends organized and framed the round-the-world record attempts. Initiated by Yves le Cornec, they included the cream of the crop at the time: Titouan Lamazou, Jean-Yves Terlain, Florence Arthaud, Peter Blake, Robin Knox-Johnson, Yvon Fauconnier and the Peyron brothers. These sometimes lively meetings were nicknamed the "accords de la Jatte", in reference to the island where the gatherings took place.

Thus was born the Jules Verne Trophy, which has been contested by the best sailors from both hemispheres, from the 90s to the present day.

The fastest catamaran of its generation

Commodore Explorer is a catamaran designed by Gilles Ollier and built entirely in carbon, a feat for its time. Under the colors of Jet Services, it holds the North Atlantic record, raced at an average speed of 19.7 knots. But it was not suitable for a round-the-world trip in the 40s e .

Bruno grafts new bows and skirts onto the catamaran, increasing its length to 25.90m. The forward beam was moved forward by 2m to accommodate a staysail stay, and 60 cm bulwarks were added to the cockpit to protect the crew from heavy seas. Last but not least, the catamaran arms, which were removable for transport, are now permanently strapped to the hulls.

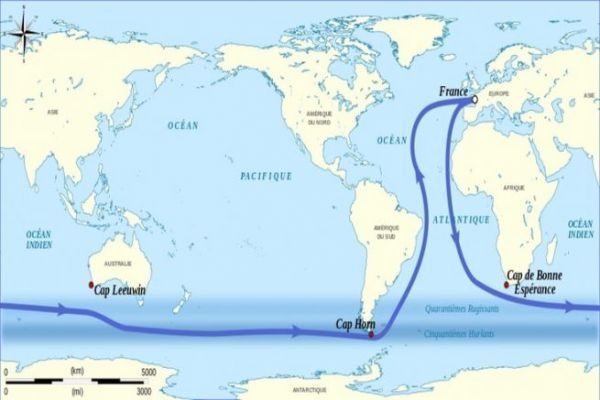

On this theoretical 25,000-mile route, Bruno and his crew have to maintain an average speed of 14 knots to break the 80-day barrier. But questions and fears abound. No large composite multihull has sailed the Southern Hemisphere seas for so long.

A small but complementary crew

Bruno Peyron, Olivier Despaigne, Marc Vallin, Cameron Lewis and Jacques Vincent made up a smaller crew than for the other projects. In Brest in January 93, things were really hotting up. No fewer than 3 teams were in the starting blocks for this first round-the-world record attempt: Olivier de Kersauson on the trimaran Charal, Peter Blake on the catamaran Enza and Bruno Peyron on Commodore Explorer.

Commodore cast off at noon on January 31, 1993. Charal preceded them by a week, and Enza by ten hours. The crew was exhausted by intense preparation in a very short space of time, but happy to set sail.

On February 6, Commodore Explorer overtook the New Zealand crew off Cape Verde. Conditions were conducive to speed, but the numerous maneuvers (the headsails were not furled) were tiring.

The crew does a lot of tinkering. The mainsail traveller rail is torn off. The mainsheet clew, though made of titanium, exploded. The spinnaker pole vang also broke, as did the malfunctioning weather chart receiver.

An invigorating start

Barely into the 40s, Commodore hit a deep low-pressure system. The catamaran was going very fast, and almost sank in a swell estimated at 10 m. The crew downsized and took refuge in the hulls. The living quarters are 7 m long and 1.40 m wide, and the headroom does not exceed 1.50 m, but they are equipped with a small heater to limit condensation

At the same time, Charal was forced to retire after a collision with a growler ripped off several meters of float.

The match is down to two. Commodore Explorer maintains a 200-mile lead over Enza. The crew is in good health, apart from Jacques Vincent, no novice to the deep south, but suffering from the humidity on board and having to be put on antibiotics.

Paternity and stratification

By the end of February, a third of the route had been completed. Two of the team members, Olivier and Cam, learn on the same day that they are going to become fathers.

Sailing conditions are rough. The mainsheet clew breaks again. One night, a wave crashed into the planking, breaching the daggerboard by 40 cm. The entire crew spends the night stratering the wall.

That same night, Enza hit a UFO, which ripped off a daggerboard and caused a leak. The Kiwi crew turned around and headed for Cape Town at slow speed.

Commodore Explorer trims its route, clocking up 500-mile days. Temperatures are dropping. An encounter with ice is a likely scenario. A watchman is on the lookout ahead to avoid a possible iceberg, which the radar cannot detect.

The crew is suffering from the cold, especially as the heating has broken down.

The world's largest catamaran reduced to a toy

At the end of March, 250 miles from Cape Horn, a very deep low-pressure system blocked the crew's progress. Impossible to escape. The swell rose. Buffet stops became very violent, and the crew frequently hovered in the hulls.

The storm intensifies. The wind reached 60 knots, gusting to 80. With the canvas dry and the daggerboards up, the catamaran was no longer a giant. For fear of capsizing and losing the men on watch, Bruno Peyron decided to take to the cape and shelter the crew in the hulls. Sailors communicate from hull to hull by VHF, preparing for an inevitable capsize. Survival bags are packed in a calm atmosphere. This fury lasts for 48 hours, before the wind drops to 45 knots, allowing the crew to get back on course and round Cape Horn on March 25.

Collisions thwart upstream journey across the Atlantic

After the Horn, Commodore's crew is licking the catamaran's wounds. The storm left a few after-effects, but nothing dramatic.

The multihull made its way up the Brazilian coast in close-hauled conditions, a particularly uncomfortable point of sail for this type of vessel.

But on April 10, the adventure almost came to an end. At 17 knots, Commodore Explorer collided with two sperm whales. A 2.50 m crack was found at the waterline, and the port daggerboard was broken. But the catamaran managed to stay on course.

As we approached the Azores, a huge ridge of high pressure extended the anticyclone, causing speeds to drop. The daily average was 4.5 knots for two days.

The wind returned, allowing the giant catamaran to sail several days at 500 miles. A collision with a log damages one of the bows.

Finally, on April 20, it's The Last Sprint. Commodore Explorer crosses the finish line in the late afternoon. Bruno Peyron and his crew made history, becoming the fastest crew around the world, with a time of 79 days, 6 hours and 15 minutes.

/

/