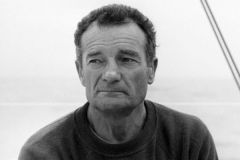

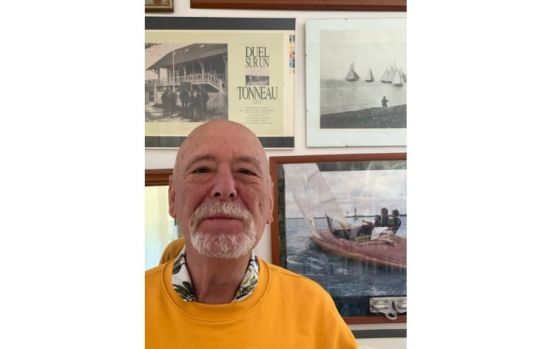

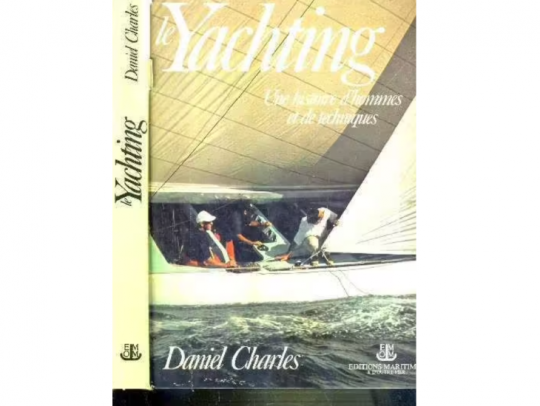

Daniel Charles has covered the America's Cup alongside Jean-François Fogel, directed the Conservatoire International de la Plaisance and defended the first French doctorate on the history of yachting. Between his reflections on innovation and his friendship with Éric Tabarly, his career is that of a passer of knowledge, always on the lookout for new ways to tell the story of the sea and its boats. Interview with this historian who, like an archivist of the soul of yachting, has forged his career through obstinacy and curiosity.

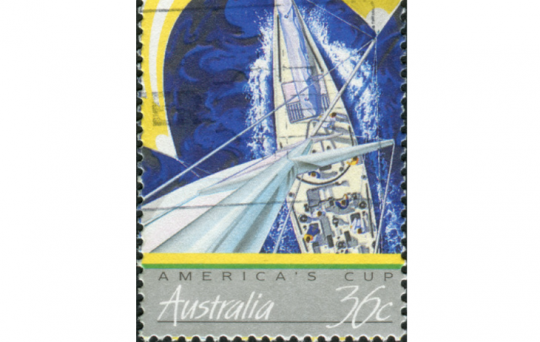

In 1987, you were awarded the CFCA prize for your coverage of the America's Cup in Release with Jean-François Fogel. How do you look back on this journalistic adventure? Have you always written "against the wind"?

No, I've always written. Even if it took me a very long time to accept that deep down, by nature, I was more of a writer than a journalist. It took me 70 years. I also juggled with language for a long time. English was my working and writing language for years. It was only for my last two books that I really got back into French. It allowed me to accept certain things.

During the America's Cup, Jean-François Fogel, then a journalist with Libération, asked who knew the most about the race. At the time, I had set up an informal network of journalists to exchange information between people who didn't necessarily talk to each other. I knew best. He set up his office opposite mine and got me involved in the "Libé" adventure. Our coverage was a success. We found all the scoops we could and told the story with enough dynamism to reach a wide audience.

The Americans had come up with an artificial skin to limit turbulence. A coating with micro-striations, generating small turbulences to attenuate larger ones. It wasn't easy to tell the story to the general public. Fortunately, our editor at the time was exceptional. He let me do two whole pages of theoretical hydrodynamics. To everyone's surprise, sales increased. Even though it was hard work. It wasn't enough to line up facts or tick off a list of information to remember. It had to be transformed into a story, an adventure. And that's what we did. A very good memory.

In 2003, in La Rochelle, you defended the first French doctorate devoted to the history of yachting. How did you come up with the idea?

I had been organizing a conference on the history of yachting in Nantes for several years. I often met history students with a passion for yachting. Many of them told me they wanted to do a thesis on the subject, but their supervisors advised them not to. Then the European decision to validate prior learning gave me an opportunity. So I turned to La Rochelle, where a professor I knew agreed to direct my thesis. That's how I got started.

In the preamble to your thesis, you write: ' for a yachting historian, I have a deplorable state of mind. I don't like old boats ''. Is this a provocation or a rejection of a certain historical fetishism?

Obviously it's a provocation. It's a way of reminding us that even old boats were young. What's interesting is not a boat that was born old. Nostalgia is not a historical discipline. It obscures things. There are old boats that are dreadful and others that are delights.

A long time ago, for my 40th birthday, I was given a ride in a Tage-Moss biplane that had been built exactly 10 years before I was born. So there you are in a biplane, it's Australia, it's hot, you're in your shirt sleeves. You realize that from an economic point of view, compared to modern aircraft, it's ridiculous, but in the moment itself, it's a masterpiece. The way the controls are coordinated, the homogeneity of the controls... It's a plane that was modern when it came out. And when we set up the "conservatoire de la plaisance", the only criteria we used to select boats were those that were modern at the time they appeared. For example, let's take the case of Suhaili, Robin Knox Johnson's boat in the 1968 Golden Globe. Suhaili was born old. It wasn't a modern boat when Robin built it in Bombay in the years 65-65, but the use he made of it was totally modern. So it's not just the shape of the hull or the architecture. And that's what's interesting.

What do you think the history of yachting reveals about modern society?

When I was writing my thesis, it wasn't easy to choose a subject. As a writer, I was used to making a living from my pen, so I tried to make the most of my subjects. My thesis supervisor told me I had to go further. So I opted for the history of yachting as a representative model of progress. The idea was to prove that progress exists as such, that it can be modeled and that the history of yachting is a valid model. All of a sudden, as my thesis neared completion, I discovered through all these reflections that innovation contingencies were appearing; criteria by which we can't predict that innovation will arrive here, but we can predict that it will pass through there. You have to study progress as if it were an animal; that's how you understand it.

Éric Tabarly called you "the living encyclopedia of yachting". What was your personal relationship with him, and what did he teach you?

As you say, my relationship with him was "personal". For 30 years, I wrote a column in a Belgian magazine that he received free of charge. It was the first thing he read every month. It made him laugh. Besides, he liked my books. I made him see boats in a different way. Sailing with Eric was an experience. We organized a classic boat rally on the Gironde, then a second one. For this second rally, we were wondering which boat to take.

A few years earlier, I had spotted two wooden scows in the Middle-West. I had a buyer for one of them, an old scow, and proposed to Patrick Tarbaly, Eric's brother, to buy the other. We opened the container in Bordeaux, at the start of the Gironde Rally. One of the boats was for Eric, the other for his brother. Eric found himself in front of this scow where nothing was as usual. Everything worked differently. For example, a scow is rectangular, so when it heels, it doesn't luff. What needs attention is not to keep the mainsail tucked in, but to keep the jib tucked in, because that's what keeps the boat from capsizing. We had an Anglo-American journalist friend who had done a lot of scows, who explained how it worked to Eric. I had to translate for him, as English wasn't really Eric's thing. In a scow, in light airs, the helmsman has to go downwind with a wet butt. If your butt is dry, you're not in the right place to heel the boat. Eric found himself on the scow as if he'd known it all his life. It was absolutely astonishing to see how much he'd made it his own. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of boats, and I was presenting things to him in a different way from what he knew. That was what interested him. It made him laugh, and he loved to laugh.

You directed the Conservatoire International de la Plaisance in Bordeaux, then the largest nautical museum in the world. What was your museum project?

We had 13,000 m2. During the 3 years the conservatory ran with me, we had around 980 linear meters of boats, not counting engines, objects... I've always been interested in exhibitions. For example, I did an exhibition on the America's Cup. In 1985, '86 and '87, the French were really involved in the competition, and a French committee even commissioned someone to do an exhibition on the America's Cup at the Corderie de Rochefort. The person snapped in their fingers and they came looking for the fireman on duty, telling him: you've got 7 weeks to design and build the exhibition. As the mayor had to go on vacation, he reduced the deadline to 5 weeks. In the end, we produced the exhibition, which was even presented at the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie. Subsequently, Henri Bourdereau, General Secretary of the Fédération des Industries Nautiques at the time, expressed the wish to see the creation of a position for a curator of nautical industries. So I worked on this project.

/

/