Born in 1949 in Watermael-Boitsfort, Belgium, Daniel Charles has dedicated his life to the study of nautical heritage. A naval architect and journalist, he is the author of nearly thirty authoritative works on the history of yachting and its technical innovations. Through a career punctuated by collaborations and in-depth research, notably on multihulls and their introduction into the America's Cup, he shares with us a journey shaped by over 60 years of experience and passion.

You were born in Watermael-Boitsfort, Belgium, and began working with the press at the age of 14. What inspired you to explore the nautical world back then?

I knew I wanted to sail when I was 6 or 7 years old, but I wasn't able to start sailing until I was 13. In fact, my first interest was more in naval architecture than in sailing. It was a desire to understand boats, and I saw no reason to do anything else. It was a way of traveling. It was an interesting technical problem. It was a way of opening up to the world. Afterwards, when I started sailing, the fact of looking for the wind, listening to how it's going to go... I found it irresistible. With my parents and brother, we built a Fireball in the parents' bedroom on the second floor. We had to dismantle the window to lower it down the façade! I really liked the Fireball, the model I'd chosen. I was almost 14, and already very interested in scows.

We were the first to import two scows from America in 1996. That was before we started building them for the Mini Transat. For me, the E-class scow remains the ultimate dinghy. The adjustments are complex, but I think my two best memories of sailing a boat are in a scow.

So, what is a scow? An E-class scow is 8.50 m long, around 80 cm at the withers, 2.20 m wide. Two daggerboards, two rudders. 350 kg. 27 m2 of sail area. The same sail area as a Dragon, but 8 times less weight. It's a way of designing a monohull that's closer to a catamaran, since the scow is shaped to balance the centerline as much as possible. These are totally extraordinary boats. I wasn't at all surprised to see this solution prevail in the Mini Transat, and now in Class 40 and IMOCA. It's a completely different way of sailing. It's had a big impact on me. Probably more so than with catamarans, trimarans or praos. Even if I was very active in the development of praos, the scow is really a totally magical machine.

Between 1970 and 1982, you designed some fifteen boats with extreme characteristics, including Tahiti-Douche (the world's largest prao in 1980) and Eka Grata (the first cruising prao in 1981). What were your guidelines for naval design? What technical or creative constraints did you set yourself?

I was at the start of the 1968 Transat. I was 19 years old. I saw the very first Atlantic prao, Cheers, take the start. I thought to myself: this is a totally idiotic way to commit suicide. Except that the boat came third in the Transat. It was the first time a multihull had made the podium in this race. It shook me to the core. It showed that I hadn't understood the film at all.

One year, I went to see Dick Newick. In Martha's Vineyard, he took me for a drive to show me the places where Joshua Slocum had lived. During the drive, he explained his principle of the prao, and I was very convinced. The prao is a single-hulled trimaran, but with exceptional load-carrying capacity. Later, Cheers was rotting, so I brought her back to France. The boat is now a listed historic monument. It's a special experience to see the boat compete, and then, 40 years later, to be the heritage expert pushing for it to be recognized as a historic monument. It shows the speed of ideas and progress.

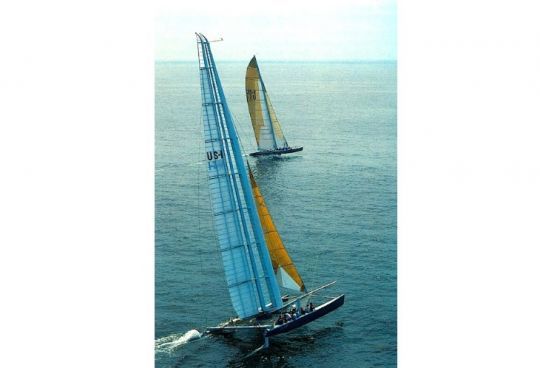

Sir Robin Knox-Johnston was the first person to circumnavigate the globe single-handed, non-stop, in over 312 days, and I think the acceleration of naval architecture is breathtaking. When the catamaran arrived in the America's Cup, we were insulted beyond belief. It was a betrayal. A few years ago, I proposed to an American museum to exhibit this story: radio silence. And yet, when we did Stars & Stripes 88, it was completely futuristic. A catamaran with a rigid sail and a dozen flaps. We had it made at Rutan, the aeronautics factory that had just built the plane for the first non-stop round-the-world flight.

It was extraordinary to go from the wood-smelling shipyards of my childhood to a factory that was building, at the same time as a wing for an America's Cup boat, drones for Egypt and a twin-engine short-landing aircraft to transport troops. Today, it takes five times less time to sail non-stop around the world single-handed than it did in 1970. No generation before us has experienced such acceleration.

For you, at what point does an innovation become relevant in naval design: when it performs well, or when it fits into a historical logic?

It's not our place to judge. Take the example of Stéphanie Kowlek, a laboratory technician at DuPont. In the 1960s, she started experimenting with polymers again, thinking that this polymer was really strange, that there was something to investigate. She persisted, convincing a spinneret specialist to try and draw a thread from it, which he initially refused, fearing damage to his machine. Finally, he accepts. That thread is Kevlar. Today, people say that Stéphanie Kowlek invented Kevlar. But in reality, she didn't invent it in the strict sense. The process she used for her first tests was not the one that was subsequently adopted: there was too much waste, too many irregularities. On the other hand, when she invented Kevlar, what interested her was getting this polymer out, seeing what was in its belly and making yarn out of it. As an inventor, she had absolutely no idea that it could be used to make bullet-proof vests, sails or fabrics.

Invention means putting together things that are, a priori, unrelated. Innovation is born of this mixture. And each time, very different profiles contribute to its emergence. But what's fascinating about innovation is that, in the end, it's the public who decides. It's not the inventor who decides. It's the user.

In 1987, your legal research led to the introduction of multihulls in the America's Cup. How did you perceive the resistance of the purists? Was it a victory for law or vision?

It was a bit of a Pyrrhic victory. Admittedly, we had a small business that was doing very well. We'd just experienced one of the finest editions of the America's Cup in 86-87. It was an extraordinary show. And then, all of a sudden, we had to start all over again. A moment of enormous tension. Let's come back to innovation. Specialists are sometimes the worst judges of innovation. Take the America's Cup. The IACC ( International America's Cup Class ), successors to the 12mJI.

A group of experts met to establish the new gauge, but above all, the use of prepreg carbon was out of the question, as it would require high temperature curing, and therefore a huge additional cost. As a result, the gauge limits hull curing temperature to 75 degrees. In 1990, when the IACC gauge was adopted, you needed between 105 and 110 degrees to work with prepreg carbon. 5 years later, you could do it at 60 degrees. But the gauge hasn't changed. As a result, everyone switched to prepreg. The hulls went from 4 tons to 1.8 tons. The total weight remains unchanged, so the 2.2 tonnes gained are put into the keel. The immediate consequence is that less hull width is required. These boats, designed to be between 4.50 m and 5 m wide, end up at 3.60 m. So, was this a necessary innovation? It doesn't really matter.

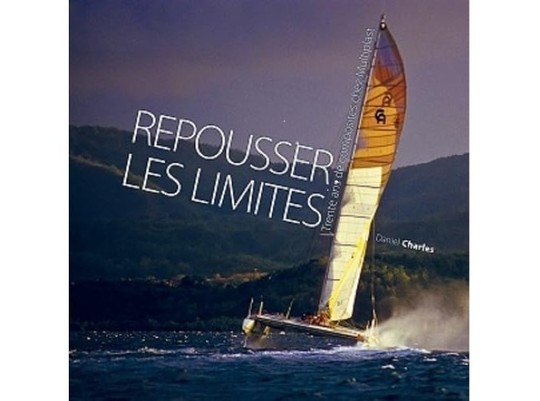

You've written a book about Multiplast and Gilles Ollier. What fascinates you most: the material, the man or the building site?

For years, I had been closely following the development of offshore racing outside the rules... outside the "establishment". Many racers had made their memoirs. And that didn't really satisfy me. I thought the best way to tell the story of the beginnings of this free ocean racing was through a construction site. When I had the opportunity to do the book on Multiplast's 30th anniversary, it was just what I was looking for. I did, however, insist on being able to tell the good and the bad, the successes and the failures. Initially, they asked me to do this book, which was to be a mini-edition of 400 copies. In the end, 2,000 copies were printed, and it was their calling card for 15 years.