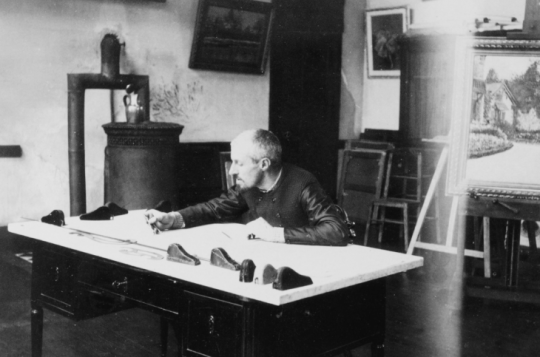

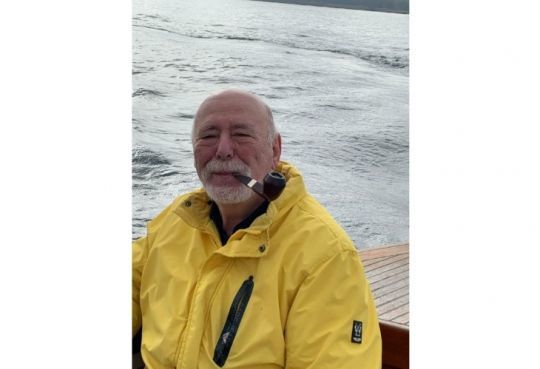

From Gustave Caillebotte's underestimated role in naval architecture to the evolution of nautical popularization, Daniel Charles has always sought to tell a different story of the sea. Rather than following traditional patterns, he proposes a reading in which technique is set within a cultural perspective, and where passion gives relief to history. In this interview, he talks about his discoveries, his thoughts on transmission and his view of the future of yachting.

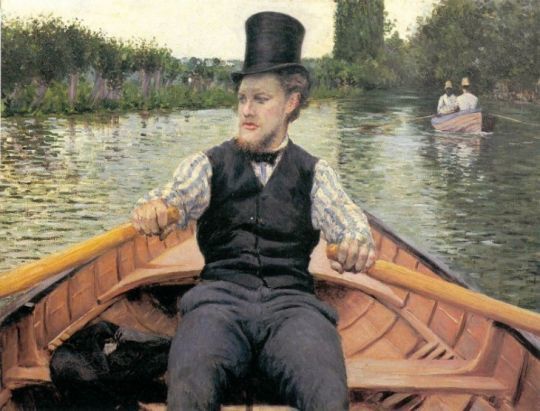

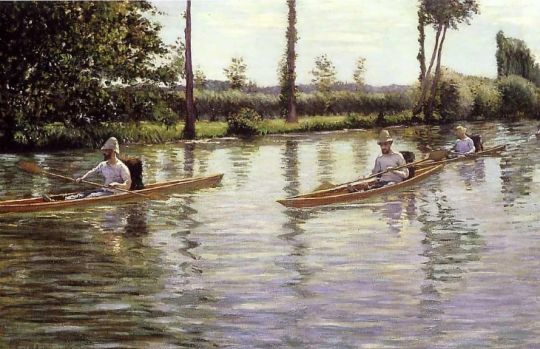

You've published a biography of Gustave Caillebotte, revealing his role as a naval architect. Why this angle, and how did his work influence you?

Le Bonhomme is interesting, even fascinating. You shouldn't look at this book through today's eyes. At the time, we knew nothing about Caillebotte. Caillebotte had one painting, Les Raboteurs de parquet, and one legacy. He was much better known for his will than for his painting. Today, he's considered one of the major Impressionists. That wasn't the case 30 years ago, and it wasn't the case during his lifetime either.

When I started this research, there were incredible grey areas. My dear Marie Béraud, who had done the catalog raisonné of Gustave Caillebotte, fell off her chair when she discovered that Caillebotte was a naval architect. She was completely unaware of this, even though she had spent her life working on Caillebotte. On the other hand, when I visited Daniel Beach, who was the curator of the National Stamp Collections in Great Britain, he often told me about the Caillebotte brothers' collection. It's now in the British Museum, as part of the collection of the man who acquired the Caillebotte stamp collection. For 48 years, the Caillebotte brothers have been among the founders of philately. Yet the London Philatelic Society, like the British Museum, was completely unaware that Gustave Caillebotte was also a painter. So everyone looks in their own little garden and doesn't have a complete view of the landscape.

We had a big "Impressionists on the Water" exhibition in San Francisco and at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, with 250,000 visitors. It was based on all the research I'd done, and I published a lot on it. The role Caillebotte played with the boat is extremely poorly perceived. When we organized the first Caillebotte retrospective in Northern Europe, in Bram, Copenhagen and then Brooklyn, the Germans were much more open. They even brought in a 30-square-meter replica of Caillebotte. We exhibited all the half-shells cut by Caillebotte on a wall, among other things.

How would you define a "boat of heritage interest"? Is it a cultural, technical, aesthetic or other notion?

I've defined what makes a boat of heritage interest. What does it mean? What does this boat represent? Sure, for the Sangria that sailed around the world with a cab driver, it has meaning, but that doesn't mean all Sangrias have the same. What did this boat do? What influence has it had? Beyond the concept of a boat of heritage interest, invented by Gérard d'Aboville, and to which I made my technical contribution, what seems essential to me is that, with a boat, it's not the boat that counts, but the gesture. Taking on an old boat, like the J classes that are racing together today, raises questions. For example, the owner of Velsheda lengthened his boat because it was a little smaller than the others and he wanted a bigger one.

Similarly, a broker convinced an owner to restore Ranger, but to make it 40 tons heavier and round off the deck to create more space. It doesn't make sense. What makes sense is to really get back to the authentic gestures.

If you take the case of Mariquita, it's quite typical. They took over the only 19-meter J still in existence. I'd known her before on a mudflat in England; everyone knew her, she was a sacred cow. They decided to rebuild the boat, not to win the classic boat regattas in the Mediterranean with electric winches and all the rest, but to compete mentally with Edward Fickman, her skipper in 1912. So they made a 31-meter-long boat, with a 22-meter boom weighing as much as a Rolls Royce. They did this to make it sail by hand. They rediscovered the gesture in a somewhat surprising way, because the first time the 18 crewmen wanted to hoist the 450-kilo mainsail by hand, they couldn't coordinate until they started singing. The gesture. It's the authenticity of the gesture that's important.

The La Rochelle Maritime Museum has Joshua, Moitessier's boat. Today's Joshua is the original hull built by Mehta. The boat is a listed historic monument. I can tell you, having known her very well in Bernard's day, that you don't get the gesture any more. Firstly, because when you entered the boat, you had to enter through the top of the deckhouse. The aft bulkhead of the deckhouse was 3 mm sheet metal. You got in at the top, and with the tip of your toe, you tried to touch the end of the tube that served as a step along the bulkhead. You lean on that. And then, as the end of the tube had been polished by Bernard's toes for years, you'd slip, and take the 3 mm of sheet metal between your two legs! Now, when you step into Joshua, it's like stepping into a modern boat. Yes, it's normal for Joshua to be modernized, because it's a boat that sails, that takes on lots of people, and it has to be safe. Today, it's nothing like the original Joshua, with its masts made from telegraph poles, its shrouds with cable ties and the half-dozen bicycles that used to be on the beach in the Sausalito marina when Bernard was there. So there's the problem of the survival of this kind of thing. What are we going to do with the AC 75s today? What future do they have?

What's your take on the current popularization of boating, with its social networks, YouTube and new forms of storytelling? What should be passed on to the younger generation?

When I was young, I thought that old people didn't understand anything. Today, I find myself in that position, so I feel a bit like the last person to judge. However, in the twelve years I've been teaching at the School of Architecture in Nantes, I've been struck by the extent to which students' curiosity has diminished. In 12 years, I've seen that curiosity fray, and I hope it will reappear, but it seems that few people are really passionate. Passion now seems to be a privilege of the older generation. I'm not complaining personally, but I do find it a little disappointing. People today don't really seem to think outside the box any more, they don't explore new horizons that much, and that's a shame.

Too often, we separate technique from pleasure. Yet technique is an adventure in itself. It can be exciting, and what brings it to life is breath. In the end, it's the pleasure we give boats that makes them vital. I've written a huge book, an adventure that's a little grotesque and asocial from a certain point of view. The book's main character is a man who, in the 1930s, travels to Polynesia. He is a professional painter. In his sketchbook, he draws horizontally. On one side of the page, there are Polynesian hotel posts drawn in pencil, and on the opposite page, there's a section of a vertical steam engine with the two cylinders one on top of the other. What's fascinating is that he finds the same poetry in the Polynesian carved motifs and in the perfectly designed mechanics. I think you really have to approach technique in this way: look for the poetry in the technique. You have to see the excitement, the wonder. If you don't try to understand how things work, you lose that magical aspect. Personally, in my writings for nautical magazines, but also as an animator, I've always tried to tell the story of technique like a real love story.

The embrace of piston and cylinder can be intense, as can the relationship between man and boat.

Do you have a nautical regret: a boat you didn't build, an idea you didn't push, or a story you didn't write?

These are not regrets. Choices have to be made. There are only decisions to be made. I've tracked down an adventurer, Hans von Meiss-Teuffen. It was he who made the first long sailings of over 130, 140 days on pleasure boats. And all in the middle of a war, which makes his feat all the more remarkable. He's an exceptional man. I found him, researched him and devoted a whole subject to his life in the courses I teach. In addition, a friend of mine, Karine Bertola, Ella Maillart's biographer, has made an interesting discovery: Hans von Meiss-Teuffen and Ella Maillart had been more than buddies towards the end of their lives. Karine brought out an excellent book on Ella Maillart's navigations last year, and I hope she will go so far as to write a complete work on Hans von Meiss-Teuffen, based on the documents she has found. That would be a great story to tell.

Having spent a lifetime dissecting the history of yachting, how do you see the future of yachting in 50 years' time?

I'm not very optimistic, to be honest. It really depends on the standards, but on the whole, I don't think yachting is going in the right direction. It used to be a way of life, but now it's a sport. Up until the 1980s, around 320,000 copies of nautical magazines were printed every month, mainly on paper. Today, we print just 80,000. It used to be that people bought several nautical magazines a month to keep up to date, to experience boating on a daily basis. That's no longer the case. A few years ago, in 2012, I had the opportunity to sail on the Côte d'Azur, but I didn't see any dinghies or anything. The whole popular base has disappeared.

One of the most secret figures is the number of yacht clubs that have disappeared in France, particularly on rivers, over the last 50 years. This is of no interest to the French Sailing Federation. It's all about competitions, medals and... money. A 50-member club on the banks of a river doesn't make any money, but that's where the roots of yachting lie. For example, I learned to sail on the Meuse. We formed a small club with a few friends in an old barge. Today, this club has become one of the most prestigious in Belgium, but in France, river boating is in decline. Only the sea seems to interest, dominated by competition and, very often, by a somewhat hegemonic Breton culture.

How would you like us to sum up your career to date? Boat historian, architect, chronicler, passer of memory... or simply the man who has always sailed against the current?

I don't know if you could say that I've sailed against the tide. I simply followed my own path, without trying to revolutionize anything. I don't consider myself a revolutionary. I try to remain honest. In the end, it's up to you to judge.

/

/