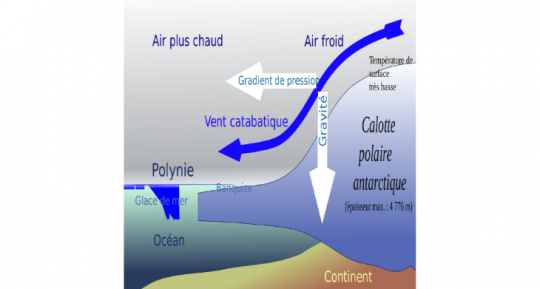

The katabatic wind is a meteorological phenomenon that is often poorly understood, but which can represent a major hazard for sailors. This downslope wind, which generally forms when a cooled air mass becomes denser than its surroundings, then rushes towards the shallows, accelerating its movement at high speed. Although this phenomenon most often occurs in mountainous or polar regions, it can occur on any terrain where the conditions are right. Here are a few explanations to help you better understand this phenomenon and anticipate it during your navigations.

The katabatic wind mechanism

Katabatic winds arise when an air mass, cooled by radiation or contact with a cold surface (such as a glacier or mountain), becomes denser than the surrounding air. This cooling creates a thermal imbalance, resulting in downdrafts. This phenomenon is often associated with a temperature inversion, where the colder air remains trapped close to the ground, while the warmer air is higher up. The katabatic wind then sweeps down the slope under the effect of gravity, and wind speeds can reach extreme values, exceeding 200 km/h in certain conditions, such as in Antarctica or the Arctic.

Polynyas, ice-free zones in the Arctic and Antarctic, are formed mainly by katabatic winds blowing from the continent to the sea, clearing the ice from the coast.

These open spaces in the pack ice not only provide a key habitat for marine fauna, but have also attracted explorers since the 19th century, who used them as access routes for polar expeditions. Indeed, explorers such as Norway's Fridtjof Nansen, who achieved the first Arctic drift aboard the Fram in 1893, took advantage of polynyas to escape the thick ice and continue their missions. This phenomenon provides an opportunity for navigation in these remote regions, even if they remain dangerous and inaccessible.

Today, these same routes are still used by modern navigators, who, thanks to advances in technology and knowledge of polar phenomena, continue to venture into these remote areas.

Conditions conducive to katabatic wind formation

Two types of cooling can generate a katabatic wind:

-

Radiative cooling: this occurs at night, when the surface of the earth or mountains loses heat through radiation, cooling the air just above.

-

Contact cooling: this process occurs when air passes over an icy or very cold surface and takes on its temperature.

For the katabatic wind to be triggered, there must be a thermal inversion, low atmospheric pressure downstream and a sufficient slope for the air to descend rapidly.

The effects of katabatic wind on navigation

The consequences for yachtsmen can be dramatic. When a katabatic wind blows across a body of water, it can make navigation extremely difficult and dangerous. Here are a few key effects:

-

Sudden acceleration of the wind: a katabatic wind can go from flat calm to violent gusts in a matter of moments.

-

Unpredictable waves: gusty winds, sometimes combined with local subsidence conditions, can generate highly irregular waves that disrupt the heeling of sailboats.

-

Fog and reduced visibility: as the air cools, condensation can form dense fogs that limit visibility, making navigation even riskier.

Boaters must therefore be particularly vigilant when sailing around mountainous areas.

Examples of katabatic winds

-

Le Piteraq

One of the best-known katabatic winds is the piteraq, which regularly strikes the east coast of Greenland. This extremely violent wind generally blows at speeds of between 50 and 80 m/s, or around 180 to 288 km/h. Piteraq is mainly observed between autumn and winter, when Greenland's ice cap cools the air above it, causing a powerful wind to descend. This phenomenon is particularly dreaded by the inhabitants of the town of Tasiilaq, located in a narrow valley. The piteraq is capable of causing major property damage and wreaking havoc on the surrounding countryside. In February 1970, a particularly extreme piteraq hit Tasiilaq with wind gusts estimated at 325 km/h, far exceeding the power of a category 5 hurricane. Since then, Danish authorities have issued special weather alerts to warn the population of this dangerous phenomenon.

-

Le Williwaw

The williwaw is another particularly violent katabatic wind that blows in certain coastal regions of the globe, notably Patagonia. The term "williwaw" has its origins in Amerindian languages, and was first used to describe the violent gusts of the Strait of Magellan, particularly feared during winter. Its fame has spread to other parts of the world where similar winds occur, such as in the fjords of Alaska and the mountains bordering Prince William Sound.

Like the piteraqs of Greenland, williwaws appear suddenly, making them difficult to forecast, even for experienced meteorologists. This unpredictability makes them particularly dreaded by sailors navigating these regions.

In 1960, the name "Williwaw" was given to an innovative hydrofoil for the time: a 9-meter trimaran designed by David Keiper that reached speeds in excess of 20 knots.

-

Le Mistral

Although less extreme than the piteraq or williwaw, the mistral is also a famous katabatic wind. This cold, dry wind forms when the air in northern Italy and the Alps cools and descends rapidly towards the Rhône valley in France. The mistral is characterized by high intensity, often reaching speeds of 40 to 60 km/h, and can blow for several days.

This wind is a worrying phenomenon for sailors in the Mediterranean, as it can cause very rough sea conditions.

-

Le Bora

The bora is another example of a katabatic wind blowing along the Adriatic coast. This wind is particularly intense when it descends from the Kvarner mountains and strikes the Croatian coast. Bora can reach speeds of up to 100 km/h, and in some cases can even reach 150 km/h, causing large waves at sea and damage to coastal areas. The areas most affected by this wind are the cities of Rijeka and Split, where bora can occur suddenly, disrupting both nautical and land-based activities.

On December 9, 2024, an impressive image captured by a satellite, Copernicus Sentinel 2, revealed a spectacular phenomenon over the Adriatic Sea, between the Dalmatian coast of Croatia and the island of Pag. On this particular day, the Bora reached speeds in excess of 100 km/h, intensifying its blast as it tumbled down the mountains of the Croatian coast. In this area, the shallow waters of the Adriatic amplify these effects and encourage the formation of foam.

Tips to minimize the risks associated with katabatic winds

-

Follow the weather forecast: before going out to sea, it's imperative to consult the local forecast and pay particular attention to warnings about thermal conditions and the risk of strong winds. The marine service of Copernicus for example, provides high-precision ocean data.

-

Avoid sensitive areas during high-risk periods: especially at night or dawn, when conditions are conducive to katabatic winds.

-

Prepare your boat for rough conditions: make sure your boat is well equipped to cope with sudden gusts. This includes checking shrouds and rigging, as well as reefing gear if necessary.

-

Sailing in a group or having a reliable means of communication: in the event of unexpected katabatic winds, it's best to be accompanied and to have an efficient communication system to alert other sailors or ask for help in the event of a problem.

/

/