The signs of a storm at sea

As you approach a thunderstorm area, there is a sudden darkening of the sky, which in the most severe thunderstorms can turn an ink-black colour. The darker it is, the thicker the cloud. The atmosphere is characterized by its chaotic, quilted, frozen appearance, with a wide variety of clouds at all altitudes.

While the wind still seemed moderate, it suddenly becomes stronger and gusty, often bringing heavy rain. There is electricity in the air, the radio crackles, sometimes you can see St. Elmo's lights at the tips of sharp objects, or diffuse buzzing. Suddenly, a thunderstorm bursts and lightning seems to zebraise the sky.

Anatomy of a storm

To begin to describe the phenomenon, remember that thunder, lightning, lightning, and thunder are not synonymous.

Lightning is an electrical shock. Lightning is the flash corresponding to the electrical discharge. The thunder is the detonation linked to the brutal expansion of the air overheated by the lightning. And the thunderstorm is the atmospheric disturbance giving rise to the cumulonimbus leading to lightning, lightning and thunder.

Thunderstorms are cumulonimbus clouds that have gone very bad and end up exploding. Unlike the classic squalls, these thunderstorm masses extend for about ten miles, sometimes rising to more than 10 km. In other words, the phenomenon is difficult to get around.

The interior of storm clouds is made up of water in all its states, ice crystals, hail, steam, even super-cooled water (which remains liquid at a temperature at which it should freeze) and, of course, raindrops.

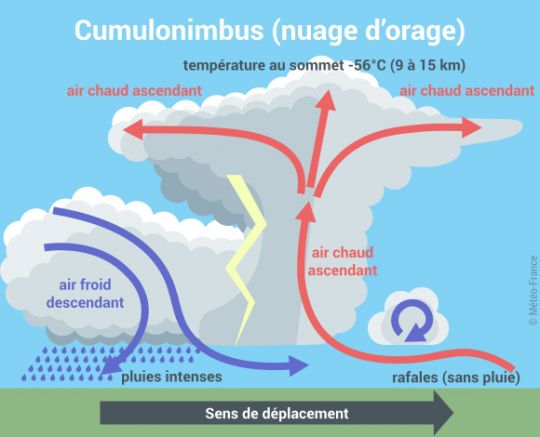

Stormy cumulonimbus

So there is no storm without cumulonimbus. It's a real thermodynamic factory: every second, a big cumulonimbus can suck up 700?000 tons of air and thus absorb 8?800 tons of water vapour. The same cloud can send back to the earth's surface 4?000 tons of water, in the form of liquid water, snow or hail.

At the front of the cloud, very strong gusts (50 knots and more) sweep across the water. The higher and wider the cumulonimbus cloud is, the stronger the gusts will be. Still in the direction of travel, hail will probably be encountered coming from the top where the temperature is close to -50 degrees. The rainy sector, very intense, announces the end of the cloud.

/

/