On the banks of the Seine or in the Mediterranean, in their regatta foulies or at the helm of their yachts, the Impressionists Signac and Caillebotte spent their time observing, but they also lived their passion for sailing with as much commitment as their profession as painters. This connivance with the elements, this intimate knowledge of the wind, sails and coastal lights permeates their canvases like a shared breath between art and navigation. They paint what they know, what they love, what they practice on a daily basis, with their hands in the salt water as much as on the canvas. Their works bear witness to this.

Paul Signac: a story of hulls and colors

Paul Signac discovered the sea as a teenager, a love that would never leave him. His first boat, the periscope Le Manet Zola-Wagner, marked the beginning of his nautical adventure. Throughout his life, he would own almost thirty boats, from simple river boats to yachts over 32 feet long.

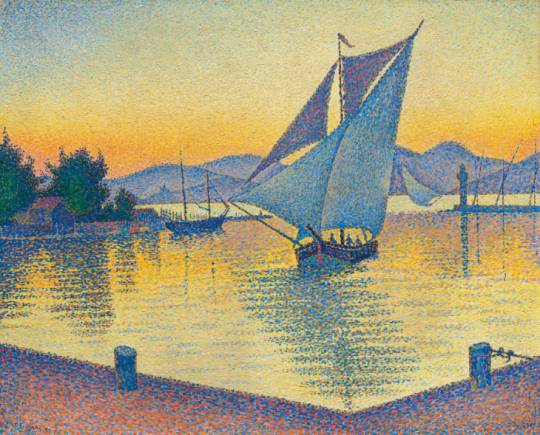

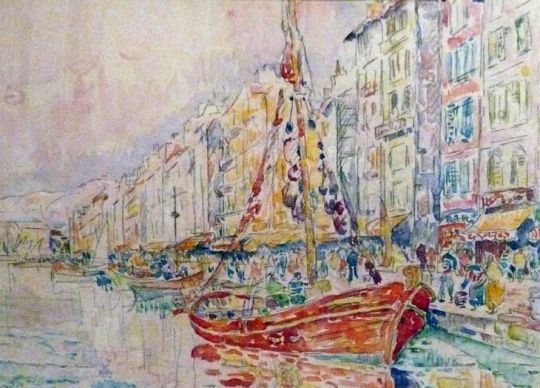

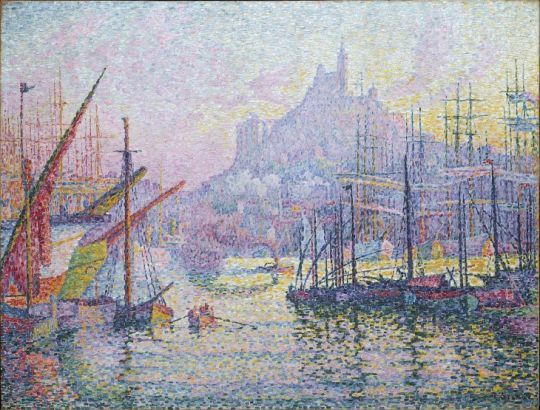

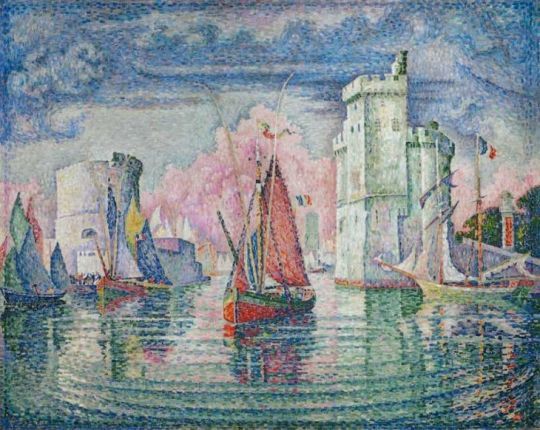

As early as 1885, Signac took Georges Seurat for a ride aboard his rowing yawl Le Hareng-Saur épileptique, in the pure tradition of the Argenteuil canoeists. The following year, he acquired Le Tub, a small catboat from which he sketched the bridges of Paris at water level. After Seurat's death in 1889, he became the owner of Roscovite, a sailboat designed for ocean cruising, which he renamed Mage, a 6-ton sloop. He set sail on a long voyage to the south, skirting the Atlantic coast before crossing the Canal du Midi to reach Saint-Tropez. In May 1892, Signac dropped anchor in a small Var port still untouched by worldly tourism. The purity of the Mediterranean light amazed him. He settled in and painted dozens of canvases bathed in light, pure colors and sea spray. In Le Port au soleil couchant, Opus 236, the sea gently calms under a gentle breeze. Every touch, every dot, bears witness to the sailor's experience. The artist knows perfectly well the way daylight sets on a hull, the way water reflects a quay.

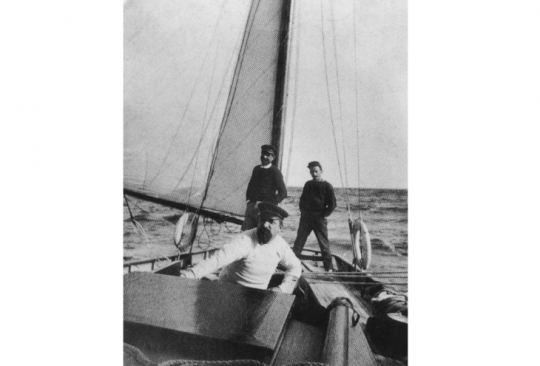

In 1894, he had a centerboard racing cutter, Axël, built in Petit Gennevilliers, which was acclaimed for its elegance. Shortly afterwards, he acquired a dinghy, Aleph, which he soon sold. He developed a passion for a small sharpie, Ubu, and acquired an American dinghy, Lark, which he named Acarus. In 1908, he bought Henriette, a motorboat. When the international measurement system was adopted, he acquired one of the first National Series racing boats, Fricka. In 1913, armed with accurate data, he built a large cruising yawl, Sindbad, and bought Balkis the same year. In 1927, while staying in Brittany, he acquired a sturdy canoe named Ville-d'Honolulu, his last boat. His painter friend Théo Van Rysselberghe testified to his abiding passion for the sea by painting Paul Signac at the helm of his boat in 1897.

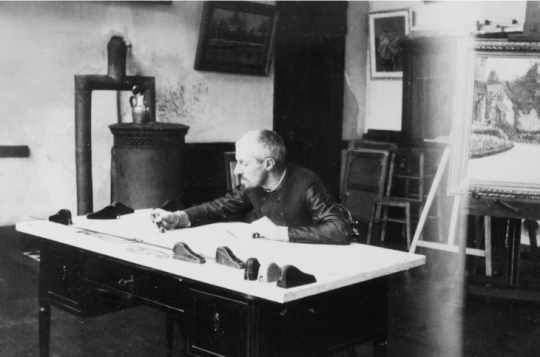

Gustave Caillebotte: the painter's eye, the sailor's hand

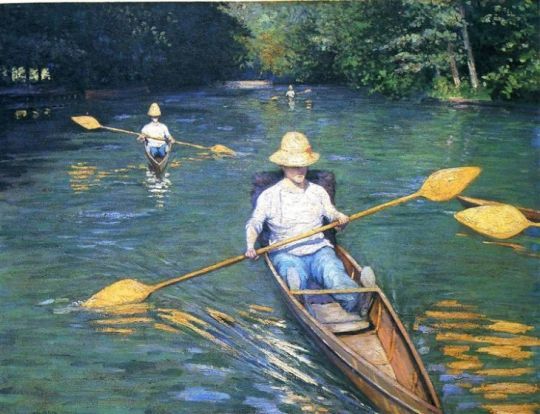

Caillebotte grew up between the banks of the Yerres and the banks of the Seine. At an early age, he learned to handle oars, then sails. This was not a mundane pastime, but a structured passion.

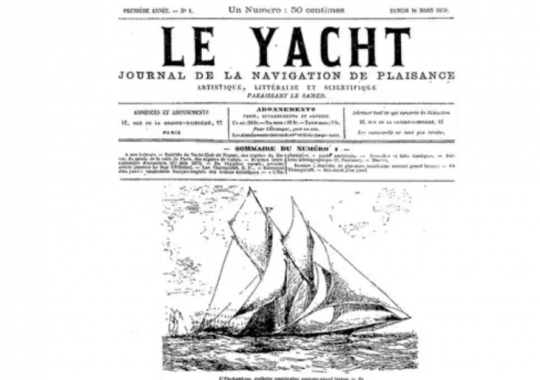

In 1878, he bought himself a real racing yacht, which he decided to call Iris. In the following years, he competed in a series of regattas and became a key figure in the Cercle de la Voile de Paris, which he co-chaired. Caillebotte was so involved in the world of yachting that he didn't hesitate to pay a substantial sum to support the creation of Le Yacht, a weekly launched in 1878 by several members of the Cercle de la Voile.

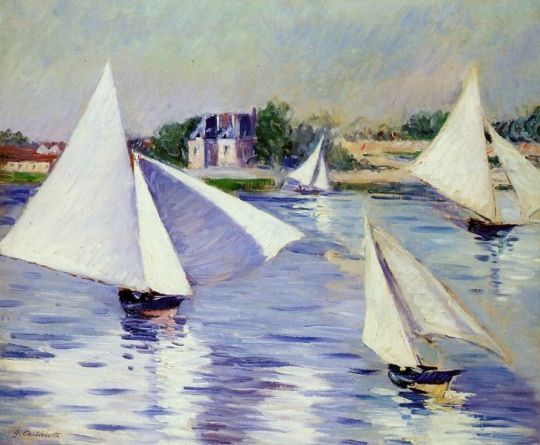

Building on his early successes at the Argenteuil regatta, in 1880 Caillebotte built Inès, a 36-foot clipper designed for competition at sea, particularly on the Normandy coast. He soon turned to a more maneuverable unit for inland waters: a 27-foot clipper named Condor. This became his boat of choice for regattas on the Seine. In all, Caillebotte owned 32 boats during his lifetime, 22 of which he designed himself.

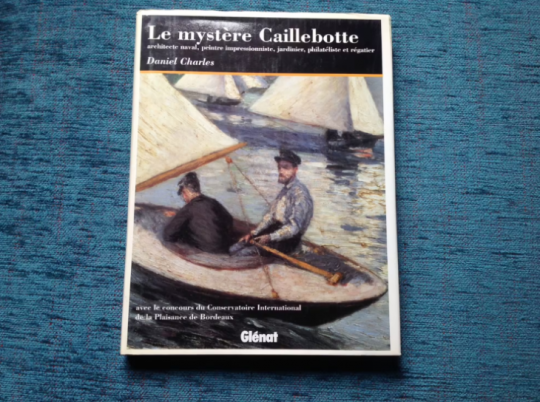

He even went so far as to buy the Luce shipyard, thereby affirming his role as a key player in the emerging yachting industry. This dimension, often overshadowed by his reputation as a painter, is detailed by historian Daniel Charles in his book "Le mystère Caillebotte: L'?uvre architecturale de Gustave Caillebotte, peintre impressionniste, jardinier, philatéliste et régatier" (1994). In it, the author sheds light on Caillebotte's technical rigor and modernity in his nautical projects.

Nautical heritage in Impressionist art

Signac and Caillebotte's interest in the sea goes beyond biographical anecdote. Both made sailing part of their daily lives as artists. They didn't paint seaside scenes for the beauty of the gesture, but because this world was theirs. They know the tension of a badly furled jib, the reflections on the water just before the wind shifts, the roll of a poorly sheltered anchorage. This dual expertise, artistic and nautical, gives their works a rare accuracy. Signac's harbors vibrate with light, but also with maneuvers.

At Caillebotte, the river becomes a regatta course where every technical detail has its place.

Together, they drew, as it were, a waterline between two worlds: that of artists and that of navigators.

/

/