In 1629, the Batavia, a flute chartered by the Dutch East India Company on a mission to reach Batavia (now Jakarta), ran aground on a reef off Australia after an abortive mutiny . While Commander Pelsaert left to seek help, apothecary Jeronimus Cornelisz, aided by his accomplice Ariaen Jacobsz, took control of the survivors and orchestrated a massacre. This drama, forgotten for centuries, resurfaced in 1963 with the discovery of the wreck, which led to major excavations on the Beacon Island site.

An in-depth conservation process

Between 1970 and 1974, under the supervision of Jeremy Green of the Western Australian Museum, several items from the wreck of the Batavia were recovered, including a cannon, an anchor and various objects, as well as beams located on the port side of the stern. Their conservation was ensured by the museum laboratories under the successive direction of Colin Pearson, Neil North, Ian MacLeod, Ian Godfrey and Vicki Richards. To facilitate monitoring and treatment, the hull beams were installed on a steel structure designed and assembled by Geoff Kimpton, a member of Green's team. This system, complemented by a stone arch also raised from the seabed, enabled each piece to be extracted independently, without disturbing the balance of the whole. The remains of the Batavia's stern are now on permanent display at the Western Australian Museum in Fremantle.

A faithful replica of the Netherlands

At the same time, the Bataviawerf shipyard in Lelystad, the Netherlands, undertook the complete reconstruction of the Batavia. Initiated in 1985 by master builder Willem Vos, this project mobilized hundreds of young craftsmen to bring her back to life.

Thanks to the use of period techniques and materials, it took 10 years to complete this boat using traditional techniques, tools and materials. Historical documents, paintings and ship specifications served as the basis for building as faithful a replica of the Batavia as possible. However, certain details, such as the ship's interior layout, remained unknown.

Batavia was solemnly christened in 1995 by Queen Beatrix. For this ceremony, she used Indian Ocean water taken from the wreck site of the original 1628 Batavia. Today, the vessel is accessible to visitors, and its maintenance continues thanks to the commitment of volunteers and students, who ensure the transmission of traditional shipbuilding know-how.

A replica of the longboat was also built and is currently on display at the WA Museum in Geraldton.

Artefacts and historical heritage

Numerous artifacts were recovered during the excavations, including bronze cannons, lead ingots, silver bars, weapons and iron tools. These objects are on display at the Western Australian Museum and testify to the richness of the Batavia's cargo and life on board.

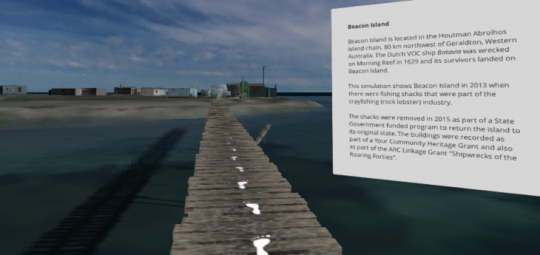

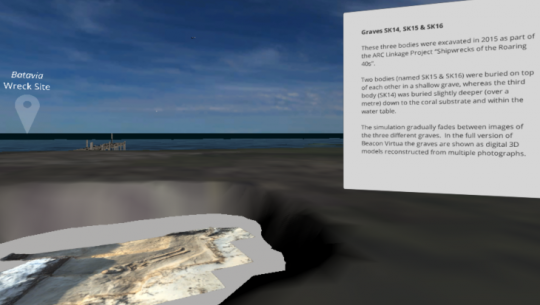

The wreck site and work on Beacon Island between 1999 and 2018 can be seen on Beacon Virtua (link foot of article), a virtual reality.

A poignant comic book to discover

The Batavia tragedy remains a case study in maritime archaeology and criminal history. It continues to fascinate historians, writers and filmmakers, because of the scale of the tragedy and the lessons it teaches us about human nature. The story of the Batavia inspired a two-volume comic strip entitled "1629, Ou L'Effrayante Histoire Des Naufragés Du Jakarta" . The first chapter, "L'Apothicaire du diable" (2022), and the second, "L'Île rouge" (2024), retrace the tragic destiny of the Batavia in a fictionalized fashion. Written by Xavier Dorison and Thimothée Montaigne, this graphic novel plunges the reader into an oppressive atmosphere where human madness is unleashed on a piece of land lost in the middle of the ocean. The fine illustrations realistically convey the harshness of life aboard a 17? century Dutch flute and the horror of Cornelisz's reign. The book is based on historical accounts and VOC archives, providing a striking visual record of this unprecedented mutiny.

/

/