Curious by nature, human beings have constantly aspired to probe natural environments, invariably leaning towards the exploration of the underwater depths. This relentless quest has led to some remarkable innovations. The first attempts were made in safe, shallow waters.

In the 4th century BC

Since ancient times, man has tried to explore the seabed using a variety of tricks, such as Alexander the Great's "Colympha" barrel, built by the marine architect Diognetus in the 4th century BC. Measuring 4 metres long and 2.5 metres high in its middle section, this rudimentary contraption, fitted with openings closed by glass plates, would have enabled Alexander and his right-hand man Nearchus to reach depths of up to -10 metres. At the time, no air system seemed to connect them to the surface, but the divers were able to breathe thanks to a system of trapped air bubbles. Illuminations dating from the Middle Ages illustrate this process.

Although groups of divers existed among the Greeks and Assyrians, the Romans are credited with creating the first military unit dedicated exclusively to underwater operations, the "urinatores", in the 4th century BC. The historian Titus Titus Livius recounts how, in the 2nd century BC, King Perseus threw his treasure into the sea to prevent it falling into enemy hands, only to recover it thanks to these trained divers. Pliny the Elder recounts in his "Natural History" how these divers began their immersion by weighing themselves down with stones and inserting an oil-soaked sponge into their mouths, which they squeezed as they descended. The aim of this technique was to create a film in front of their eyes, thus improving their vision, as the refractive index of oil in water is similar to that of the human eye.

Air gourds

In accounts of the conquest of Tyre by Alexander the Great's troops on their way to Egypt, it is said that the Greeks took divers on board their ships and, thanks to this support, succeeded in destroying the Phoenicians' underwater defenses. On the same subject, the historian Quintus Qurcio writes that the Phoenicians, in order to withstand the seven-month siege by Alexander the Great's troops, also needed the help of divers who provided them with food and weapons. They were equipped with gourds, probably made of leather, providing the air essential for their missions.

Until the Renaissance, numerous accounts document the use of various methods to enable people to breathe underwater.

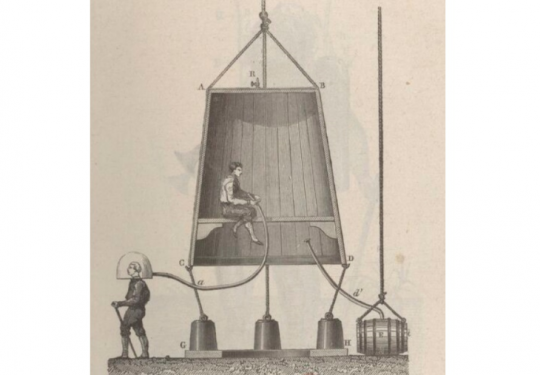

The bell in the 17th century

In the 18th century, astronomer Halley designed a diving bell made of wood and lined with lead. This innovation was presented in the 19th century by Auguste Demmin in his "Encyclopédie historique". The upper part of the bell is fitted with thick glass to let light through, and a pipe allows stale air to escape. The truncated cone-shaped apparatus (A, B, C, D) is made of lead-lined wood, with a platform suspended (G, H) by three ropes. A spigot (R), fixed at the top, evacuates stale air. On the first attempt, Halley dives with four other men for over an hour, reaching a depth of around 50 feet (about 15 m).

In the 17th century, arms merchant Hans Treileben introduced the diving bell to Sweden. In 2023, the scientific team at Sweden's Vasa Museum reproduced the bell system according to period plans, and tested the method with Lars Gustafsson, slipping into the skin of a diver of the time.

"The man boat"

But it was in the 18th century that Jean-Baptiste de la Chapelle invented the word "scaphandre", from the Greek "skaphé", basket, and "andros", man. The mathematician began theoretical research and practical trials in 1765 on a cork suit designed to float on water without swimming. Ten years later, he presented his invention in his "Traité de la construction théorique et pratique du scaphandre, ou du bateau de l'homme", approved by the Académie des Sciences. The work was republished with additions, notably concerning the possible military use of his research. A demonstration was held before the King in 1768: '' M. L'abbé de La Chapelle had long been vying for the honor of testing his cork suit in the presence of the king (...) Monsieur de la Chapelle threw himself into the water, but as he didn't reach high enough, he drifted and the king could only see him from a distance. He performed various operations, such as drinking, eating and firing a pistol. ''

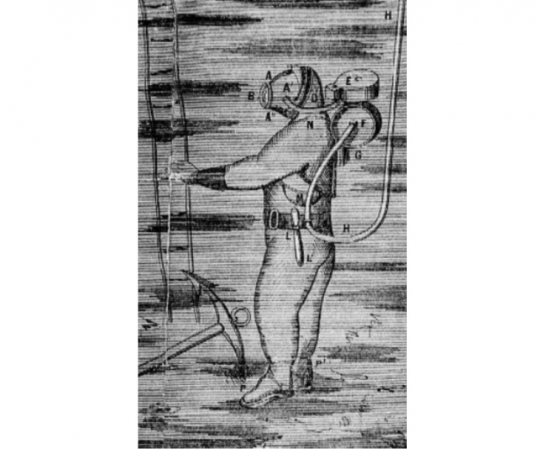

The diving suit

One invention followed another: in 1772, Fréminet developed the first rigid copper diving helmet connected to an air supply pulled behind it by the diver, called the "hydrostatergatic" machine.

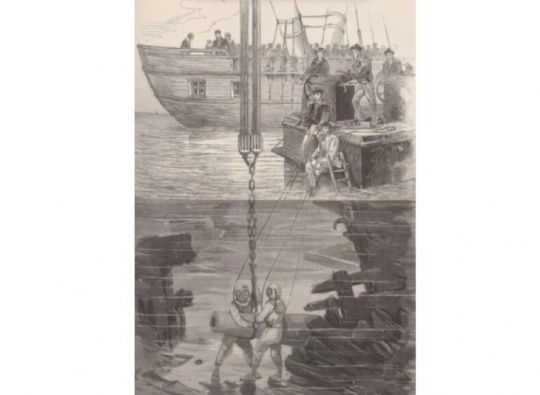

In 1797, in Germany, a certain Klingert invented the first prototype diving suit. Comprising a tin cylinder enveloping the diver's head and torso, it left the arms free. The diver wore a jacket with sleeves and leather briefs capable of withstanding pressure at depths of up to 6 or 7 meters. All the rooms were watertight, with openings for the eyes and pipes for fresh and stale air. A sort of reservoir held any water that, over time, would get into these pipes and impair breathing. Two lead weights, suspended from the cylinder against the diver's hips, kept him in a stable state of equilibrium. Finally, on June 23, 1797, in the presence of a large number of curious onlookers, a certain Frederick Joachim threw himself into the Oder using this device, and went on to saw a tree trunk at the bottom of the river. This invention, because of its flaws, did not make a fortune, but it inspired others to experiment.

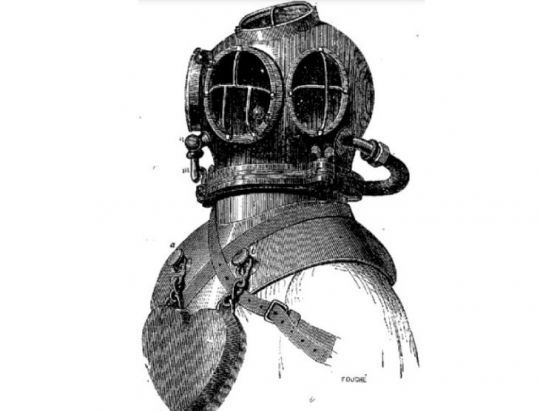

Lead soles

In 1837, a truly watertight diving suit was developed by Augustus Siebe of London, connected to a surface air pump. The shoes had lead soles. Until 1857, Mr. Siebe enjoyed the privilege of supplying diving apparatus to the French navy.

A in 1855, Mr. Cabirol, a rubber manufacturer in Paris, filed a patent for a diving suit, which he presented at the Paris World's Fair alongside other suits such as Siebe's. He introduced innovations such as the pressure gauge, which indicates the diver's pressure and depth, and an emergency stopcock, which allows the diver to breathe quickly when leaving the water. He introduced innovations such as a pressure gauge to indicate pressure and depth, and an emergency valve to enable the diver to breathe quickly upon exiting the water. Building on his success, Cabirol registered a new patent in 1860 and continued his demonstrations. One of these involved sending a convict to a depth of 40 meters to demonstrate the maneuverability of his air-pump-powered device.

The Rouquayrol and Denayrouze system

Cabirol remained the Imperial Navy's supplier until 1866, when its diving suit was superseded by the more advanced Rouquayrol and Denayrouze system.

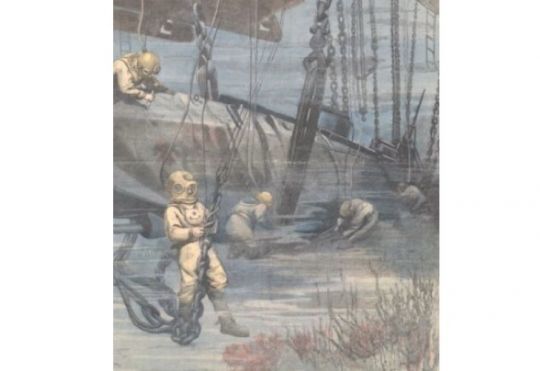

The technical challenge was not the only objective of these inventors. The diving suit quickly met a wide range of needs. It was used to repair ships, such as the propeller on the transatlantic liner Vera Cruz in 1863. It facilitated coral and sponge fishing; ship refloating, such as the Magenta in Toulon Bay in 1875; and submarine assistance, such as the Farfadet in 1905.

The search for shipwrecks and relics was also one of the possibilities, opening the way to dreams of buried treasures and cities, which were quickly snapped up by the press and popular science magazines such as Science illustrée.

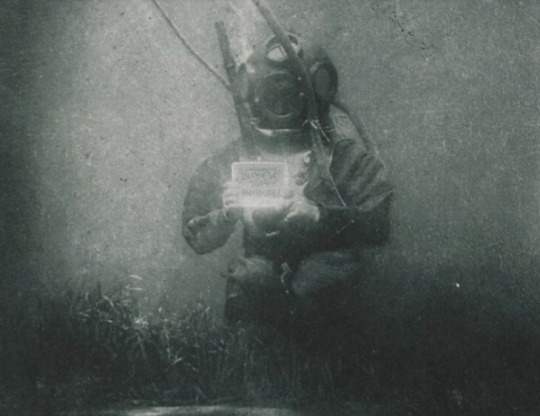

Fictional works were not to be outdone, such as André Laurie's Atlantis, or Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Archaeologists were quick to understand the contribution of this new material. In 1863, the Congrès Scientifique de France reported on the use of diving suits to probe the seabed in Grésine Bay, on Lac du Bourget, to extract pottery and a bronze axe. Other tools, such as underwater photography, were needed to complete the range of exploration equipment.

1926, the self-contained diving suit

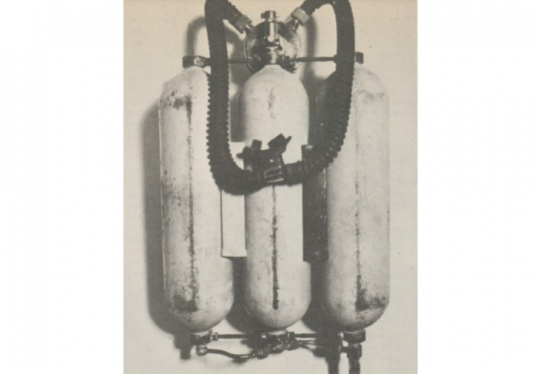

But all systems have the disadvantage of not being very self-contained, the air tank is not very efficient and the pumping of air from the surface prevents the diver's full mobility. The modern diving suit of the 20th century, fitted with a compressed air cylinder, was developed in 1926 by Maurice Fernez and Yves Le Prieur. Tests took place in the Tourelles swimming pool in Paris. The air is breathable thanks to a regulator that the diver has to operate, and the cylinder is transportable. Autonomy is still limited to around ten minutes.

In 1943, Émile Gagnan and Jacques-Yves Cousteau perfected the self-contained diving suit with the addition of an automatic regulator. Marketed in 1946, this invention quickly became a great success, giving thousands of people access to the underwater world.

Always new innovations

In 2023, new innovations continue to emerge, such as mini scuba tanks, offering autonomy from 7 to 20 minutes, with a maximum depth of 3 meters for beginners. This equipment aims to make diving more accessible to a wider public, offering a variety of uses such as snorkeling and careening operations. A hand pump makes it possible to refill this mini scuba tank autonomously anywhere. This type of equipment does, however, require knowledge of the basic rules of scuba diving.

From antiquity to the present day, underwater exploration has gone through eras of technical evolution and diversified motivations. From the stories of Alexander the Great to the latest contemporary innovations, this quest for the ocean's depths highlights human ingenuity in the face of the unexplored.

/

/