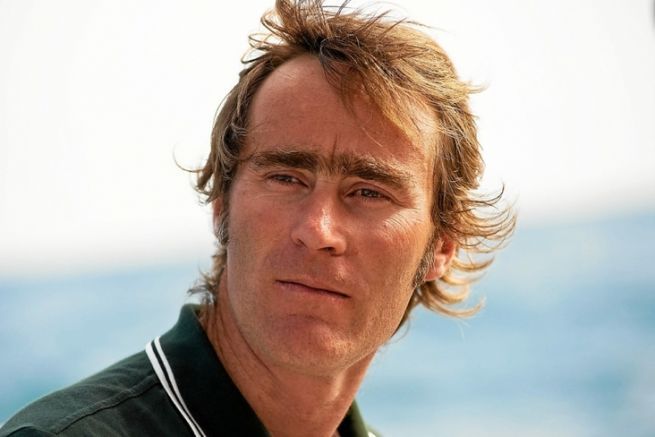

A debut on the Mini 6.50 circuit

For Sam Manuard, sailing is a family heritage. First his grandfather, who built a dinghy out of plywood, then his father who built a steel boat in the late 70's, to take his family on trips.

"The interest in sailing boats, their construction and use is a family sequel. I kind of caught the bug from them."

Sam started naval architecture by designing and building a Mini 6.50, the TipTop650. He took part in all the races of the circuit before starting the Mini Transat 2001. A race that went well and that made him want to continue in this way.

"Sébastien Roubinet, who is a good friend, gave me a great hand at the end of the construction of my boat. He also had this project to do the Mini Transat. I gave him the plans of TipTop's shape, a little evolved, and he built it. That's how I got more and more involved in the naval architecture business."

For the 2003 Mini Transat, he built 3 "protos".

"That's how it all started. That's when I turned the corner. I had a first job as a geophysicist, and I got completely involved in both sail racing and naval architecture projects. What I'm still racing and designing"

"Running and Drawing"

Sam Manuard made his debut on the Mini 6.50 circuit, before sailing in Figaro, Maxi, ORMA, Multi60, Class40, Multi50 and more recently in IMOCA.

"Almost all the racers do their training in Mini 6.50. I followed this training school which is great. I learned a lot of things: how to manage, how to draw, how to analyze, how to build. It was very rich.

I've been lucky enough to be able to test a lot of different supports, a lot of boats. That leads to asking a lot of questions about how they work, what's important, what can be transposed from one boat to another... It feeds your thinking to sail on boats that are different."

"A non-academic training"

It is thus "on the job" that Sam Manuard trains as a naval architect. Even if his training in geophysics brings him this scientific aspect, common to both professions.

"There is an aspect related to drawing, shapes, volumes, appreciation... That is not necessarily learned in books or on school benches. Building boats gives a good practical aspect: touching matter, working with materials. That was my training. Spending time on the water, cruising with my parents and racing, also helps to give you a background in naval architecture. You have to be a jack-of-all-trades in this profession. It's not much of an academic training, but you learn by doing."

Eclectic projects

Today, Sam Manuard has made a name for himself in the world of ocean racing, designing almost exclusively sailboats. A course that was a natural progression.

"I am very interested in anything that floats and anything that allows you to enjoy the element. Whether it's rowing boats, recreational boats, expedition boats, dinghies, small sailboats. I love all kinds of gear.

It just so happened that the projects came together. By wanting to, but without really trying to provoke things. And I was lucky enough to be able to work on ocean racing projects. It excites me a lot, but I also love all the issues related to cruising.

The more time passes, the more I enjoy being a naval architect is finding a solution to a given specification. Whether it's on a powerboat or something else."

In addition to his ocean racing projects, Sam Manuard also works with private owners, but also for the Bénéteau shipyard with the Seascape.

"We're launching a 72-foot monohull, a fast cruising boat for the Black Pepper yard, but designed for a client. I've also done some cruising boats for amateur builders. It's kind of where I come from. I try to be as eclectic as possible."

Keep your freedom, but work as a team

Sam Manuard works differently from other naval architects, who are often heads or hired in design offices or naval architecture firms. Depending on the project, he associates himself with the different actors necessary for its realization.

"On the big projects, I work with people who have their own companies. We go project by project depending on the size. I am rarely alone on a project. I call on people who have specific know-how: structural calculations, foil design, CFD calculations, VPP. I don't really want to have employees, I like my freedom."

"Working on concepts"

What the architect likes most of all is the work at the beginning of the projects, the development of concepts.

"When you have to find the main lines of the boat, find what is going to be important either for performance or to best meet the specifications, which can sometimes be complex. You have to find the most intelligent solutions to meet the problem. I like setting up projects. I really enjoy all the exchanges we have to get these projects started."

Do not impose your ideas and be creative

Depending on the specifications, it is important to listen to the client, to a team, or on the contrary to offer a complete and free vision.

"It's very important to listen to your client, and not necessarily to impose your own ideas, except when asked. After that, it can also be the specifications, having a free hand. But sometimes you have to meet a fairly clear set of specifications. This was the case with Seascape. To make simple boats, for leisure, adapted to a general public.

You have to try to find the right solutions, but also listen to others. Many people have better ideas and contributions from clients. Often, I have very competent clients, who know what they want, who have good knowledge. Often the exchange is very rich."

And to meet the specifications, questioning and creativity are essential. You have to be able to innovate.

"You have to approach a problem without too many preconceptions. That's the big challenge. Staying open and creative. It's hard to be creative. We often tend to redo what we have done. It's not easy to question yourself.

There is an experience that has marked me a lot on this subject. A long time ago, I gave naval architecture courses in Montpellier, to architecture students. They had no preconceived ideas about naval architecture at all, and I got a big kick out of it. I realized that not knowing anything about a subject allowed me to approach it in a much freer and more creative way. I often try to remind myself of that, to keep a fresh eye on what I'm doing."

Setting the trends

One of the roles of the naval architect is also to create trends, to innovate to find new concepts, which will be the way forward.

"There is an element of the sensory and the intuitive. That's why I say that sometimes you have to disregard what you do or what you think you know to give yourself more freedom. You have to test things. It's important to leave room for intuition. Depending on the size of the project and the means, we can validate with a scientific approach that the concepts will work, in order to limit the risk.

That's what we typically do in IMOCA. These boats are quite difficult to produce. We invest in time and R&D to validate and ensure that the concepts are good and that the dynamics of the boats will be good. It reduces the risk, but initially you need intuition and good ideas."