A conflicted relationship, but a shared technical admiration

I remember my meetings with Jean-Marie Finot as verbal scuffles: we had no chemistry. This admission makes me all the more comfortable in recognizing that this abrasive personality was the most influential French naval architect in the history of yachting. It's not a label that's easily bestowed, and " which most strongly solicits the investigations of history and the lofty speculations of philosophy "(as a 'freshwater wolf' wrote in the first canoeist's manual in 1844). Of course, to understand how Finot's concepts revolutionized the form, performance, function and appearance of sailboats the world over, we'll have to delve into the technical side...

Two schools of thought: naval architecture between "less" and "more

There are two opposing philosophies in naval architecture: the "less" school and the "more" school. The first - exemplified by artists as different as Doug Peterson and Dick Newick - believes that if you reduce sail area, you reduce the demand for stability, so you have less weight, so you still need less sail area, less stability... and in the end you might not have a boat at all. [I once teased Dick Newick by telling him that his ideal for the solo Transat was to come to the start with his hands in his pockets, from which he would extract an inflatable boat, which he would deflate at the other end;" not far from the truth "said Dick]. At the other end of the spectrum, the "plus" school adds sail area, which means adding a ladleful of stability, resulting in extra weight, which in turn means more sail area, more stability, more weight... so much so that you could end up with a boat of infinite size. An example to illustrate these two schools of thought: in 1980, the 500m speed record was held, at 36 kts, by a "plus" boat, Crossbow II, 18.28m long with 120m▓ for 1.7T; six years later, this record was raised to 38 kts by Pascal Maka on a "minus" boat, a sailboard 350% shorter. Despite their enormous differences in size and budget, the two boats had the same power-to-weight ratio, on the order of 80-100m▓ per ton...

The genius of the triangular hull: the Callipyge revolution

On a "plus" sailboat, the only way to avoid the infernal escalation of weights and budgets is to short-circuit the cause-and-effect relationship between stability and weight. The first great prophet of "plus" boats, Nat Herreshoff (1848-1938) used the refined construction of his shipyard (at the time the world's largest yacht yard, with some 1,000 employees) to reduce weight and lower the center of gravity - more stability, less weight -; he took advantage of this to invent the bulb keel, which has since become widespread. Jean-Marie Finot, another paragon of the "plus" sailboat, used a much more subtle method: he changed the geometry of the hulls.

Between Archimedes and Newton: understanding stability from another angle

In practice, stability is an arm-wrestling match. On the one hand, there's Mr. Archimedes, who applies his Principle from bottom to top to the submerged volume of the hull (summarized as the hull center). On the other, Mr. Newton applies his Law of Gravity to the center of gravity, whose position sums up the weights of each of the boat's components. During this arm-wrestling match, the forces do not vary: the weight remains the same, as does the volume of the hull; what changes is the position of the wrestlers in relation to each other.

Take a dinghy, ideally positioned with the hull flat: since the hull remains straight, Archimedes presses down in the same place he pressed down in port; however, the abseiling crew has shifted the center of gravity to windward, and the distance between Newton and Archimedes creates a lever arm, which, multiplied by the weight, creates a righting torque, and this torque counterbalances the capsizing torque of the sails. Simple.

The instructive parallel between multihulls and monohulls

When the crew can't act on the center of gravity - on a keelboat, for example - Newton doesn't move, Archimedes does: the boat heels, the volume of the hull moves to leeward, and the upward thrust does the same - in practice, Archimedes is rappelling backwards. In all cases, the righting torque remains the product of the horizontal distance between the efforts of the two scientists (the lever arm) multiplied by the weight, hair on the arm!

And on a multihull? Take a trimaran whose volume is supported at rest by the central hull. When the boat heels over, the float takes over, so Archimedes pushes under the float - zou! In other words, when stationary, the axis of heel is amidships, but when heeling, this axis shifts by half a width, completely to leeward, with such an enormous lever arm that less weight is needed for the same righting moment. So: lots of stability, lots of sail, little weight, lots of speed (but the risk of putting the boat on its roof).

Mathematical shapes for performance

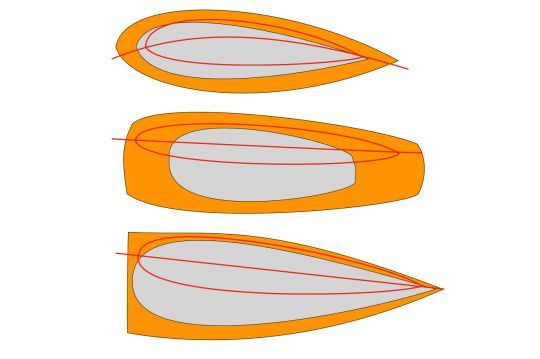

What if we did the same thing on a monohull? Herreshoff (who started out with catamarans in 1876) gave it a try around 1895, with a rectangular hull like a lasagne, which sends Archimedes pushing under its leeward side and will show the way for Jones & Laborde to follow with scows. The gain in leverage is spectacular: an E-Scow (designed in 1924!) has the same sail area as a Dragon, but needs five times less weight to develop the same stability! At the end of the 1960s - when Finot started out as a naval architect - the scow was little-known (I'll be importing the first two E's from Europe in 1996!), it was thought to be limited to lakes, Finot wanted to win races in the English Channel, and he had another idea to increase stability while retaining a real bow to cut through the waves.

...Imagine a triangular hull... Finot's first famous half-tonner (a racer class of around 9m) was called Callipyge┬ in 1971; in antiquity, it was referred to as ß╝¤¤╬┐╬'╬»¤╬- ╬╬▒╬ "╬ "╬»¤euros¤ ╬│╬┐¤, Aphrodite with a beautiful butt and the name suits this raw aluminum racer perfectly, with an ass as wide as a church door. Because of its triangular architecture, the axis of heel moves obliquely from the bow to the corner of the transom, as if we had a catamaran whose two bows merged into one. The lever arm increases, giving greater stability for the same weight...

However, this diagonal heeling is accompanied by a change in pitch that is almost impossible to predict when tracing, with curved battens and sinkers, the "old-fashioned" plan of form, based on the three traditional orthogonal views. Finot gets round this difficulty by making a clean sweep of the drawing board: he no longer draws, he calculates.

Groupe Finot: a collective adventure to reinvent sailboats

" Finot "I wrote in 1997 in "Histoire du yachting" (Arthaud)" was the first to design its hulls directly on the computer, back in 1970. At the time, these were crude applications of mathematical functions, and people sometimes wondered who decided: man or machine? Doubts were soon dispelled. And the ability to multiply variations of the same shape very quickly undoubtedly helped the French architect to perfect his revolution. "

Mathematical shapes... As early as 1962, Pierre BÚzier had developed the curves that bear his name for bodywork design at Renault; BÚziers' curves would form the basis of all 3D design programs today (in fact, CitroŰn had preceded him as early as 1959 with Paul de Casteljau, but kept his discovery a secret). In yachting, British master sailmaker Bruce Banks had already used mathematically generated shapes to design spinnakers in 1964, extending the range of these downwind sails to crosswinds with radial or star-cut spinnakers. Suffice to say, it was in the air, and someone would end up applying it to hulls - and that someone was Finot. The functions chosen sometimes led to impractical shapes (such as the frigate, difficult to mold and a remarkable crew sprinkler), but decades later they retained a confounding modernity.

A regatta record overshadowed by a major invention

Not content with turning sailboat architecture on its head, Finot also shook the myth of the genial, single-handed naval architect by creating the Finot Group. Alongside Jean-Marie were Laurent Cordelle, Philippe Salles and Gilles Ollier (the latter founded the Multiplast shipyard in 1983 and became one of the leading architects of racing catamarans, characterized by mathematical forms). The members of the Finot Group had all tried their hand at land-based architecture, and wanted open-plan layouts that broke with the codes of traditional compartmentalization. The volume available in the callipigean hulls helped them achieve this. More volume, more stability, more sail: the modern sailboat was born, and architects the world over rallied to these new principles. It is said that Finot designed 200 types of boat, some 40,000 of which were built - but in fact, the vast majority of all sailboats built worldwide over the past half-century apply the principles defined by Jean-Marie Finot in the early 1970s.

On the racing side, Finot won the Quarter Ton Cup with Ecume de mer, his first big success; in the 1970s, J-L Fabry's extraordinary 'Revolution' collected laurels. Then, with his new partner Pascal Conq, came a series of Imoca boats; in 1996, he succeeded on 'Aquitaine Innovations' in piling up more than 50m▓ of sail area per ton of displacement - a weight/power ratio worthy of multihulls; even if this boat was unlucky, it defined the class for two decades. Finot's racing record is therefore brilliant, on a par with the greats.

And yet... all these cups, all these trophies pale behind this unparalleled, unique title of glory: that of having invented the modern sailboat.

/

/