On June 20, 1894, in Le Havre, the Abel Lemarchand shipyard launched a pilot cutter commanded by the young pilot Eugène Prentout. He named her Marie-Fernand, after his two children. His vocation? To run to merchant ships sighted on the horizon, bring a pilot on board and guide them, without breaking, to the quay. At the time, there were around forty of them competing in this free and bitter profession, on a sea riddled with shoals and currents.

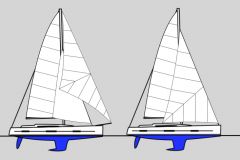

The sails bear the registration H23, accompanied by a black anchor: a sign of recognition, but also of pride. The H stands for the maritime district of Le Havre, and the 23 indicates that this is the 23rd cutter registered in this official register. These letters and numbers, drawn large on the mainsail, enabled the ship to be quickly identified from the shore or at sea. They were also a mark of authority in the âeuros pilot's trade, and sometimes a trump card in regattas: you had to be seen, and fast. To this day, Marie-Fernand proudly wears this emblem, a testament to her identity and to the memory of the cutter-pilot from Le Havre.

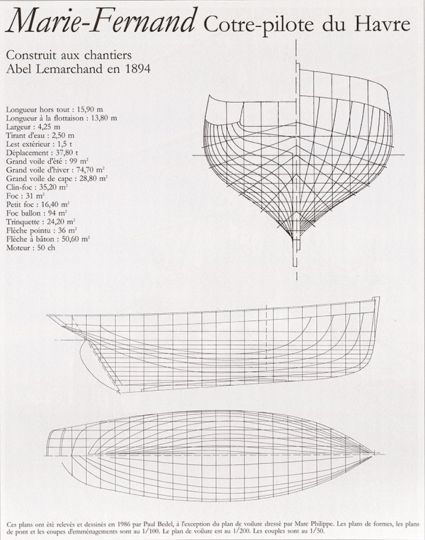

Marie-Fernand quickly made a name for herself: barely a month after being launched, she won the prestigious pilots' regatta. Her architect, Abel Lemarchand, incorporated yachting techniques to lighten the structure and improve performance: steam-bent frames, external ballast... Marie-Fernand was a prototype, a sailboat ahead of its time, designed for speed and maneuverability.

The rough life of swallows

At the turn of the 20th century, the pilot's job was a battle against the wind and the weather. Cutters don't wait: they head out to sea, watching for smoke, reading the sea, taking their chances. They are independent, and therefore in direct competition with each other. That's why their sailboats, the famous pilot cutters, have to be the fastest, in order to be the first to meet an approaching ship. The first to arrive wins the contract. Their slender, dark silhouettes have earned them the nickname of the Channel Swallows.

At the end of the 19th century, maritime traffic exploded in the English Channel. The booming port of Le Havre attracted more ships from all over the world every day. In these demanding waters, even the most seasoned captains know they have to rely on a local man: the pilot.

Because once you've landed âeuros that dreaded moment when you're approaching the coast without visibility or reliable landmarks âeuros few people refuse the invaluable help of these expert sailors. At the time, the compass was one of the only reliable navigation instruments, beaconing was rudimentary, and radio did not yet exist. Sailing by sight, in a fog-covered sea churned by treacherous currents, was often like gambling one's cargo, or even one's life, in a lottery.

Pilots know every coastal trap: shoals, sandbanks, malicious rocks, narrow passes. They've mastered the use of the depth sounder, the lead that is allowed to spin across the bow to "read" the seabed and recognize the famous staircases of the English Channel, those variations in depth that signal the right course... or a fatal error. This sensitive reading of the seabed, a true pilot's sixth sense, is the first thing that mousses are taught as soon as they come aboard.

On board, the crew often consists of a skipper, a deckhand, a seaman and, sometimes, a boatman. The order of passage is determined by lot, the maneuvers are acrobatic and endurance is absolute. When the wind eases, the sail is reduced: one reef in the mainsail, staysail reefed, and breeze jib. When the calm sets in, the canoes are launched, and the men row, sometimes for hours on end. And yet, these men do not falter.

In 1905, Marie-Fernand rescued seven sailors from the schooner Marthe, a heroic deed that earned her pilot the Légion d'Honneur. It was just one of many feats in a profession where courage, seafaring instinct and knowledge of the coast's minutest traps were all part of the daily routine.

From piloting to fishing, from pleasure to oblivion

In 1915, the pilot's profession changed: steamers replaced sailing ships. Marie-Fernand was sold for fishing, before crossing the English Channel. She changed her name, first to Marguerite II, then to Leonora. For over sixty years, she sailed under the British flag.

She cruises first in Cornwall, then along the coast of Scotland, in the hands of Archibald Cameron, a solitary sailor enamored of silence and whisky. At the helm of this old cutter, he makes his way up to the Hebrides, where Leonoradevents a rustic yacht, halfway between an observation post for the Royal Navy and a floating refuge for an aging captain and his faithful dog.

Back to Le Havre, 63 years later

In 1985, L'Hirondelle de la Manche, an association based in Normandy, was planning to build a replica of a pilot cutter from Le Havre. Miraculously, an English owner came forward: Leonora was none other than the last Le Havre pilot cutter still afloat. The purchase was made without a budget, but with a strong conviction.

In June 1985, Marie-Fernand returned to her native port, escorted like a hero. Pilot boats, helicopters and an entire flotilla greeted her in the harbor of Le Havre, decked out like a ship of state.

On the quayside, former pilots and young volunteers discover a shared emotion. The boat is there, worn, but very much alive.

A patient renaissance

At the Honfleur shipyard, thirteen frames were replaced, the planking was redone and the dead parts restored. The rigging was rebuilt, and the pilot room carefully reconstructed from old descriptions.

All this is done in a spirit of fidelity, without denying the marks of a century of navigation. In 1986, Marie-Fernand was classified as a historical monument. Éric Tabarly agreed to be its godfather. A rare recognition for a workboat, which for decades was invisible to the world.

Navigate again

In 1992, she took part in the Voiles de la Liberté in Rouen, then in Brest 92, where she proudly held her place among the traditional sailing ships. Since then, Marie-Fernand has returned regularly to major maritime gatherings, supported by the L'Hirondelle de la Manche association, its volunteers and enthusiasts.

In 2004, she entered a new phase in her long life: a complete overhaul was entrusted to the Guip shipyard in Brest, a leading centre for the restoration of maritime heritage. The restoration involved the identical reconstruction of several key elements: the stem, stern, keel and several couples were replaced, while the deck was completely dismantled. Approximately 70% of the original planking was retained, demonstrating the remarkable quality of the wood used in 1894. The total budget is 370,000 euros, financed by a combination of public funds, the association's own resources and public subscriptions.

Mechanical propulsion was also rethought: the boat was fitted with a Max-Prop variable-pitch propeller and a 115-hp Nanni Diesel engine, the installation of which required a singular adaptation. The engine cannot be installed in line with the hull, which would weaken the structure, so it is mounted slightly off the starboard side.

On July 13, 2008, Marie-Fernand was relaunched in Brest, at the heart of the maritime festivities, in the presence of the widow of Ãric Tabarly, the ship's historic sponsor. While the hull is complete, finishing touches are still being added alongside the quayside: repowering, rigging, installation of the âeuros mast repatriated from Normandy âeuros, and interior refurbishments.

Sea behaviour true to its legend

21 m long, 4.20 m wide, with a draught of 2.50 m, Marie-Fernand carries 225 m² of canvas. She's fast, very canvasy, and comfortable âeuros even if she does have a nasty lump. Her sculpted helm, her high-stepped flèche, her black and white livery: everything about her evokes the elegance of the past.

It's hard on the arms, but rewards the effort. It's a bit wet, but goes well. Sailing maneuvers remain physical: taking in the mainsheet during a gybe requires two seasoned crew members who are perfectly synchronized. But at the helm, she holds her course, docile, even in fresh winds.

âeuros¨

A living heritage

Even today, every Wednesday, volunteers repair, maintain and pass on their skills. They are carpenters, mechanics, retired harbor workers or simple lovers of the sea. Between 20,000 and 25,000 euros a year are needed to keep Marie-Fernand going.

Far from being a fixed museum, it's a school boat, a memory boat and a pleasure boat, which regularly embarks seasoned sailors and curious visitors. More than ever, she is a voice of wood and canvas, telling the story of a vanished profession: that of sailing pilots.

/

/