Under the direction of Bernard Ficatier, a former naval carpentry teacher, Scanmar trains specialists to use technologies such as photogrammetry and lasergrammetry. The aim of their work is to scan and then archive boat forms of heritage interest that are destined to disappear. By working together with these players, Scanmar strengthens its commitment to preserving our nautical heritage.

Can you tell us about the Scanmar association and its main objective?

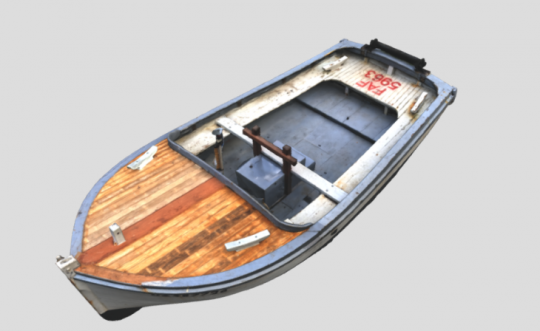

The main mission of the Scanmar association is to digitize our maritime and river heritage. The fundamental idea is to begin a process of digitizing boats in 3D. An alarming fact has come to light: many boats are disappearing without a trace, initially built without precise plans, often based on half-hulls, models or neighboring models. This lack of documentation makes it imperative to safeguard the shapes of these often unique boats. It is crucial to act before they are deformed by the wear and tear of time, deteriorated by fungi and other wood-eating insects, and to preserve a tangible trace of their existence.

Another essential aspect of Scanmar's work is the training of skilled individuals in the use of these digitization tools.

What are the criteria used to select the heritage boats to be scanned and archived by the association?

The rarity of the boat and its relevance to the history of maritime typology are determining factors. Scanmar often favors boats with no architect's plans, particularly those built before the 1930s, when building without plans was commonplace. From the 50s onwards, as the arsenals began to operate and regulations were introduced, the practice of building boats to plans became widespread. In 1900, for example, Maritime Affairs registered 178 Douarnenez-built boats. Sadly, many of these boats have all but disappeared, often destroyed for use as household fuel or for other practical purposes. A few remnants remain, bearing witness to the ravages of time, but they are few and far between. To ensure a rigorous selection process, we have formed a small scientific committee made up of members of the Scanmar association.

What techniques does Scanmar use to scan the hulls of heritage boats?

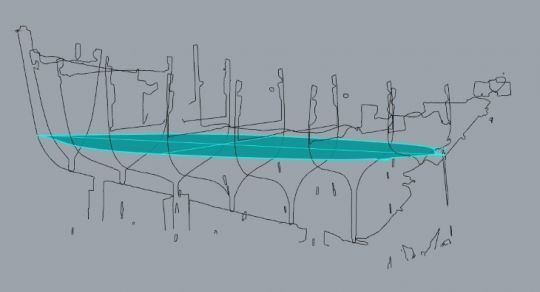

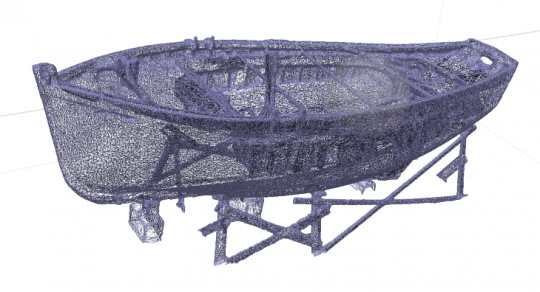

We use state-of-the-art techniques such as photogrammetry and lasergrammetry. The use of modern scanners coupled with computers enables us to achieve speeds up to 50 times faster, and accuracies up to 1,000 times greater. The data obtained is stored in the form of point clouds or meshes.

On a 10-meter boat, it takes just one hour to prepare for the scan, in order to be able to rotate around the boat. The total time depends on various factors, such as space and light conditions, but where it used to take a day, it now takes just 3 to 4 minutes.

It is sometimes sufficient to scan only half of a boat to make a plan... when the boat is grounded on one side... on the shore, for example. Indeed, as almost all boat hulls are symmetrical, the process can be applied. For gondolas and Hobie Cats, for example, it's a different matter, as they feature subtle asymmetries.

What limits have you come up against?

First of all, despite having scanned over 75 boats in the last year, we are concerned about the quality of our backups. The volume of data generated is considerable, representing terabytes of memory. We are faced with the crucial question of storage: should we opt for hard disks or magnetic tapes, and how can we guarantee the long-term accessibility of this data? What's more, we have yet to establish a relationship between the digital weight of our work and the rarity of each boat scanned. How can we make the most of this data in the context of maritime heritage research and preservation? There are many possible uses for the digital surveys: distribution on servers, integration into museum exhibitions, publication on websites, or deduction of detailed boat plans. However, we are aware that every addition of data contributes to digital pollution, so we strive to strike the right balance.

We also intend to make available raw images (photos, videos, point clouds) that we haven't worked on, so that anyone can freely exploit them. We are also able to produce 3D reconstructions but for the moment, we're focusing on image storage.

Finally, we are concerned with the long-term preservation of our data and how it can be used in the future, complying with the standards set by the Museums of France to ensure that it can continue to be read 10 years from now. They recognize the value of our work and encourage us to use our surveys to create lasting plans, surpassing those produced manually in accuracy.

Does the Scanmar association work in collaboration with other players in the field of maritime heritage preservation?

Our privileged partners include the Port-musée de Douarnenez, as well as training centers such as the Ateliers de l'Enfer in Douarnenez, the Skol ar Mor school near Saint-Nazaire, and the École d'Architecture Navale in Nantes. Internationally, Scanmar also collaborates with the National Maritime Museum of Cornwall in Falmouth, England. In addition, the association has begun a promising collaboration with the Monuments Historiques for the Brittany region. These partnerships take a variety of forms, from simple awareness-raising interventions to training courses. For example, Scanmar organizes sessions to publicize the existence of its digitization tools and train interested parties. We also welcome trainees who come to Douarnenez to learn photogrammetry, thus helping to pass on the skills needed to preserve our maritime heritage.

/

/