In 1968, the Sunday Times announced the Golden Globe Challenge, the first non-stop, single-handed round-the-world race, an extreme event that challenged sailors to tackle the 3 great capes without assistance. Francis Chichester's 1966-67 solo circumnavigation of the globe with one stopover in 226 days had already captured the imagination. This time, however, the promise is even greater: the ultimate consecration awaits whoever succeeds in completing this journey without ever touching land.

9 skippers take the plunge, including iconic ocean racers Bernard Moitessier, Robin Knox-Johnston, Nigel Tetley... and an outsider, Donald Crowhurst. A British engineer and entrepreneur, he has little experience of the high seas, but harbors a wild ambition: to design a revolutionary trimaran and prove that he can compete with the greatest.

Today, the name Donald Crowhurst is often associated with fraud and deceit. Yet his story is first and foremost that of a man faced with an unbearable dilemma. Involved in an adventure beyond his control, he finds himself trapped by his own illusions and the pressure of the outside world. Rather than admit failure, he maintains the appearance of a winning race by constantly postponing the moment of truth. But in the end, faced with the magnitude of the lie and the isolation of the ocean, he makes a radical decision: to stop running and face reality, even if it means losing himself in it.

This first part retraces the beginnings of his adventure, his aspirations and the first obstacles he had to overcome.

A risky gamble and a poorly prepared trimaran

The story begins in the autumn of 1968, when Donald Crowhurst, an electronics engineer with no significant nautical experience, decides to take the start of the first edition of the Golden Globe Race a non-stop, single-handed round-the-world race promising a £5,000 prize to the fastest sailor. The only condition: competitors must set sail from a British port between June 1 and October 31, 1968, and return to the same place. This race, launched by the The Sunday Times the company attracts seasoned sailors, but Crowhurst, a family man and until now a Sunday sailor aboard a 20-foot sloop christened Pot of Gold despite his lack of preparation. But first, he needed a boat.

After being turned down by the Cutty Sark Committee to borrow the Gipsy Moth IV however, he turned to another solution: a trimaran, which he considered to be the ideal craft, even though he had never sailed one. To finance his project, he embarked on what could be his greatest tour de force.

Whereas his company Electron Utilization and his main investor, Stanley Best, demands his money back, Crowhurst turns the situation to his advantage. Rather than crumble under the pressure, he convinces him that the best way to get his money back is to invest in the construction of his boat. The company then emphasizes the use of the trimaran as a test bed for its innovations, while stressing that the visibility generated by its participation in the race would contribute to the success of its projects.

However, a less favorable aspect of the agreement is that the loan is guaranteed by Electron Utilization this means that, if it fails, the company risks bankruptcy. Crowhurst was thus able to raise the funds needed to Teignmouth Electron a trimaran built by Cox Marine in Essex and equipped by JL Eastwood in Norfolk. The delay became obvious: at the end of June, when the Cox yard had just begun building the hulls, Ridgway, Blyth and Knox-Johnston were already at sea, engaged in their round-the-world voyage.

Teignmouth Electron crowhurst's trimaran is a poorly designed boat. Far from racing yacht standards, she had numerous structural flaws, which, from the very first hours at sea, put her solidity and ability to stay on course to the test. None of the ingenious inventions that the novice skipper had imagined for the boat were connected, including the flotation bag at the top of the mast which was supposed to inflate in the event of the boat capsizing. Despite this dubious construction, Crowhurst's audacity had won him funding and sponsors who saw in him a sailor capable of achieving the impossible.

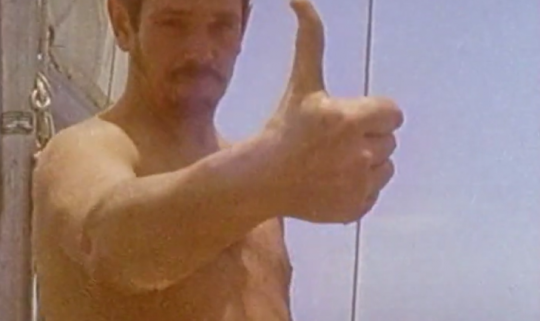

But right from the start, Crowhurst's inexperience shows. He moves about the deck of his trimaran, giving the image of a hasty, disorganized figure as he embarks on this mad challenge. Moments later, he retraced his steps to tackle the untangling of his jib and staysail halyards, stuck at the top of the mast. On October 31, 1968, he finally left the port of Teignmouth, England, for a voyage that would last almost 9 months - the beginning of his troubles.

The technical agony of the Teignmouth Electron

Crowhurst was soon confronted with the harsh reality of single-handed sailing. Teignmouth Electron suffers from numerous technical problems. Two days after his departure, while still within sight of the Cornish coast, the first technical problems began. With no spare parts on board, he had to dismantle other parts of the machine to make repairs.

A few days later, halfway across the Bay of Biscay, he realized that the forward compartment of one of the hulls was flooded by water seeping through a faulty hatch. Shortly afterwards, other compartments began to leak, and as he had been unable to obtain adequate piping for the bilge pumps, he had no choice but to empty them with a bucket.

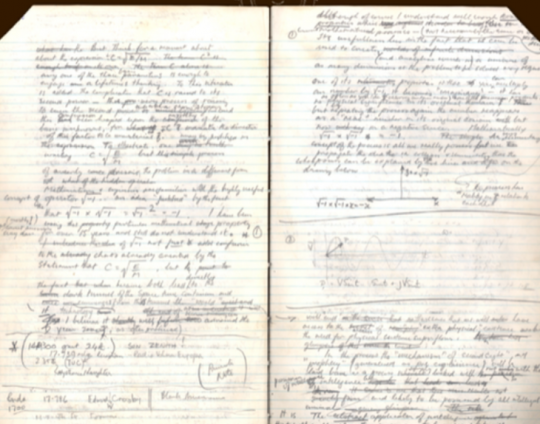

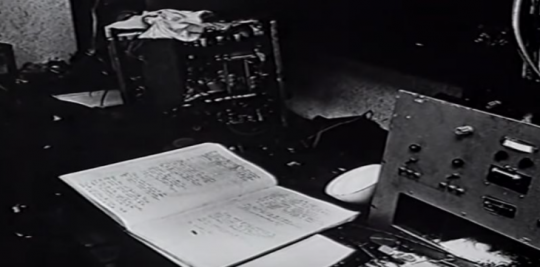

Two weeks after leaving Teignmouth, his generator breaks down, victim of water from another leaking hatch. '' This damn boat is falling apart due to a lack of attention to technical details!!!! crowhurst wrote in his diary. A few days later, after drawing up a long list of repairs to be carried out, he concluded that his chances of survival, if he continued, were 50-50 at best. The idea of abandoning the race began to take shape; yet in the film he was making, all was well.

Crowhurst found himself at an impasse. Giving up now would mean not only the end of his reputation, but also the bankruptcy of his business and the loss of his mortgaged home, for him and his family. Giving up was not an option. He soon realizes that his speed forecasts were largely unrealistic: he thought he could cover 220 miles a day, but in reality, he only manages to cover half that, even in good conditions.

Catching up with the other competitors or hoping for victory becomes increasingly unlikely, unless something exceptional happens. The race to Cape Horn becomes an ever-tightening trap. Faced with rough seas, Crowhurst decided not to face the waves and sail in the direction of the race. Rather than turn back, which he knew would be an admission of failure, he opted for a radical strategy.

The falsification trap

So, after just 5 weeks at sea, Crowhurst began to falsify his position. From December 5, he created a false logbook, calculating fictitious trajectories with his sextant and compass, but never leaving his real position.

To make his deception credible, he follows the weather forecasts for the areas concerned and writes fictitious comments as if he were actually experiencing the conditions he describes. And so the great deception takes off. After a few days' preparation, he feels confident enough to send his first erroneous'' press release claiming to have covered 243 miles in 24 hours, a new world record for a solo sailor. In truth, he only covered 160 miles, a personal best but far from a world record.

As Crowhurst slowly makes his way across the Atlantic, his imaginary double has already rounded the Cape of Good Hope and is heading for the Indian Ocean. Gradually, thanks to misunderstandings and manipulations by his agent in the UK, his positions become more and more fanciful, to the point of giving the illusion that he may well win the race.

At the same time, the real Crowhurst was still roaming the Atlantic, hidden exactly in the zone he had mentioned a few weeks earlier as being ideal for a sailor wanting to conceal his position and rig his round-the-world voyage. On March 29, he reached his southernmost point a few kilometers from the Falklands, 8,000 miles from home, before beginning his ascent towards the Atlantic. To avoid his radio signals being intercepted, he remained silent for almost 3 months, between mid-January and early April, claiming another generator failure.

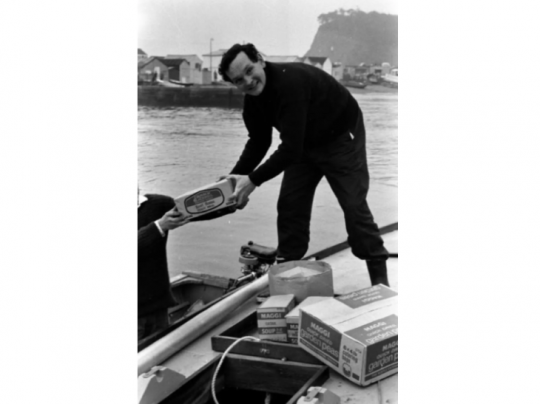

The trimaran Teignmouth Electron becomes a ghost ship, its route erased by manipulation. Crowhurst chose to "survive" on the spot. He even stopped in an isolated bay near Buenos Aires, Argentina, to procure the parts needed to repair one of the hulls, which was beginning to deteriorate. Although he was welcomed and registered by the local authorities, this stop, in violation of the rules, went unnoticed.

But the lies can't go on forever. Crowhurst's mental and physical exhaustion begins to take its toll as he loses touch with reality. The ocean, once a source of freedom, becomes a suffocating prison.

In the second part of this report, we look at the psychological drift of Donald Crowhurst, trapped by his own lies and isolation. As he tries to maintain the illusion of success, the story of his fraud becomes a mental ordeal, a downward spiral that leads him to a final decision.

/

/