Minimum equipment for a descent into the sun.

At the bottom of the cockpit trunk of Maya, a 10-metre Melody, is a temperamental autopilot that will have to be repaired en route, and a slightly undersized windvane gearbox, lent by a friend and which we'll have to install during a forthcoming stopover.

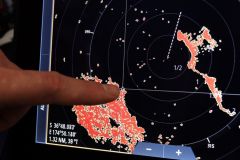

We're at the beginning of November, and after a summer of work that ended late and a boat to get ready for the big start, we decided that it was important to have a well-prepared hull and sails in good condition" that'll do the trick ". A small portable GPS, a cartography game supplemented by computer navigation software, a sextant, and off you go!

How many sailors have we come across on the pontoons shouting enviously about how lucky we are to be setting sail? And when we realize that the sailor and his boat in question lack nothing to set sail in his turn, the answer is invariably: " Oh no, I'm missing this, I'm missing that ". In fact, what's missing - even if the notion of being ready is entirely subjective - is often the courage to cast off.

We set sail on November 6, with a crew of 3: the captain, his 15-year-old son (who will accompany us to the Canaries) and myself.

We're in for a roller-coaster Bay of Biscay, which is going to wear us out for the next 3 days: 30 to 35 knots of NE'ly wind, with a residual W'ly swell, and a chaotic, annoyed, almost angry sea. With no autopilot or windvane gear, the 2 adults on board took turns at the tiller, day and night. And believe me, in the middle of November, the nights are long... ill-equipped in terms of clothing (obviously), it's terribly cold (due to the Nordet wind) and even a hot cup of coffee before the watch, i.e. every two hours, doesn't warm us up.

In principle, the arrival in Spain, the cervesa and the tapas will comfort the atmosphere on board by a few degrees. But with 12-hour days at the helm, tendonitis, neck and back pain began to appear. The descent from Portugal is punctuated by life-saving stopovers. The change of scenery and the endless nights racing with luminescent dolphins make us forget the aches and pains of our already strained bodies.

Finally, let's see what this pilot has to say, and install the windvane gear...

In Peniche, we decide to try and repair the auto pilot, but to no avail as it has finally given up the ghost. We laboriously install the windvane gear.

It will only work occasionally, and only in good weather. This "toy" cannot claim, as it should, to replace a crew member who neither sleeps nor eats. It's certain that if we have to continue the adventure and the navigation with two at the helm, my already aching back won't last the distance.

I don't sit well at the helm, and despite the cushions and other arrangements I've cobbled together to improve my seating position, I find this alternation and dependence hard to bear. Either one or the other is screwed to the helm, and the dependency of having to ask the other to take the helm if only to go to the toilet or make a cup of coffee. No time to read either. Every 4 hours, the priority is to sleep, cook, clean or maintain the boat.

During a 7-hour helm shift, which I deliberately lengthened to provide the captain with an effective rest, I had to use acrobatics as ridiculous as they were amusing to open the cockpit locker to retrieve the "WC" bucket, do "my business" in it, empty its contents overboard, then stow it away again. All this without letting go of the helm and keeping my course, of course!

Sometimes, the most incongruous challenges allow us to surpass ourselves in ways we could never have imagined on land!

Turn of events.

A few days before arriving on the island of Graciosa in the Canaries, a wave a little more vigorous than the others, delaminated the submerged blade of the windvane gear. This set the scene for the rest of the navigation. No pilot, no windvane gear, no navigational aids until the West Indies. While it's possible to tie up the helm and reef the boat, Mélody is far too rolly to be sailed on downwind points for long.

Once we'd arrived in the Canary Islands, we wondered whether the best solution would be to take on board some hitchhikers for the rest of our voyage, which would take us to the West Indies via Cape Verde. As agreed, at Christmas time, the son disembarked and we headed back to France for a few days.

The pontoons of Las Palmas have a good number of hitchhikers, "arms to steer". Could this be the solution to our problem? What if something happened to one of us and one of us was left alone to manage the boat and, above all, steer 24 hours a day for several days or even weeks?

If we've skipped the hardware, perhaps this is an opportunity to share a human experience?

/

/