At the dawn of the 20th century, wooden lifeboats - open, fragile and ill-suited to extreme conditions - were unable to withstand the onslaught of the North Atlantic. Convinced that a safer alternative existed, Norwegian engineer and sailor Ole Brude had a hermetically sealed, unsinkable lifeboat built in 1904, with which he hoped to complete an Atlantic crossing in the company of three other crew members. Despite widespread skepticism, the voyage was to go down in maritime rescue history. This is his story.

An idea born of a near-miss

Born in 1880 in Alesund, on the west coast of Norway, Ole Brude spent part of his childhood in the United States before returning to Europe. There, he signed on as a seaman aboard the Athalie, a merchant steamer operating between America and the Old Continent. It wasn't until a crossing in 1898 that he became fully aware of the dangers of traditional lifeboats.

Of this period, Brude says: '' In 1898, I was a sailor. Near Newfoundland, we weathered a terrible storm that left us on the brink of shipwreck. The lifeboat had been blown to pieces by the devastating waves on deck, depriving us of any chance of survival. I had nightmares about it for nights on end, all the while thinking about what a safe and reliable lifeboat could be. When I landed in the spring of that year, the idea of such a boat pursued me and I decided to make an attempt to realize it. I drew a few sketches and, around Christmas, my first plans were drawn up

It was this traumatic experience that inspired Ole Brude to embark on a visionary project. Driven by the conviction that a safer alternative existed, he began work on a prototype radically different from traditional wooden lifeboats. Inspired by the metal hulls of ships, he designed a totally enclosed lifeboat, unsinkable and capable of withstanding the worst storms. A reliable lifeboat, capable of saving lives on the high seas, even in the most extreme conditions.

Uræd: a prototype designed for survival

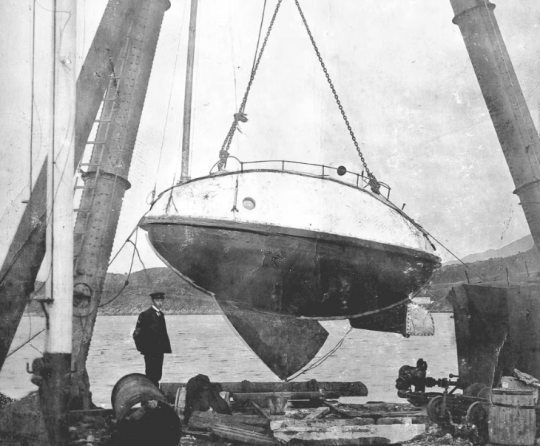

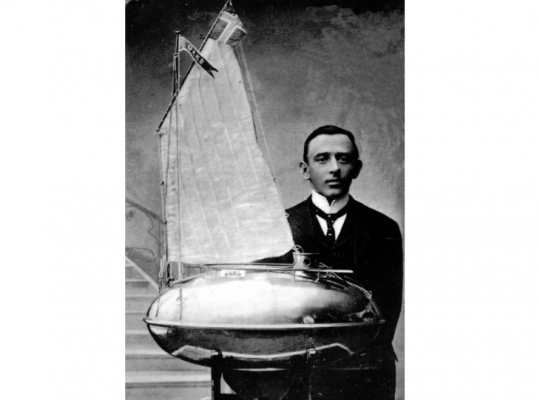

After graduating from the Haugesund School of Hydrography, Ole Brude fine-tuned his project, which culminated in the construction of the Uræd, a canoe with unprecedented features. At the beginning of 1904, he entrusted its construction to the Alesund Mek Værksted & Slipanlæge workshop.

With a length of 5.48 m and a "diameter" of 2.43 m at the beam, this egg-shaped boat is built from 4-mm-thick riveted steel sheets. The hull has a double bottom into which a ballast is integrated to ensure the boat's stability. Its special shape makes it exceptionally resistant to capsizing and absorbs the impact of waves, while a sturdy liston all around the boat protects it from collisions. Equipped with a folding mast and an auric sail, Uræd is designed for sailing . In flat calm conditions, it can also be manoeuvred using oars. The dinghy is also fitted with an observation kiosk with 4 portholes, providing the reduced visibility necessary for navigation. Access to the interior is via two watertight hatches at the bow and stern, no more than 60 centimetres in diameter.

The canoe's interior is optimally designed for utility, with a continuous elliptical bench running throughout. This is partitioned to provide dedicated storage for water and food, and also includes a toilet with integrated pump. Ventilators on the bow and sides ensure good air circulation. In an emergency, when there's no time to launch the dinghy in the conventional way, simply cut the mooring lines and rush aboard. The openings are quickly closed and the wait begins. The canoe can then be released from a great height. In the event of sinking, it briefly sinks with the whole ship before floating back to the surface.

Uræd was designed to meet the specific needs of an emergency boat accommodating around 40 people. For a model intended for commercial transport, Brude designed a smaller 14-foot version capable of carrying between 25 and 30 passengers. At the time, open wooden canoes were the norm, and the concept of a hermetically sealed steel canoe seemed far-fetched. Maritime authorities and shipowners remained skeptical. To prove the effectiveness of his invention, Ole Brude decided to cross the Atlantic in his prototype.

A test run on an Atlantic crossing

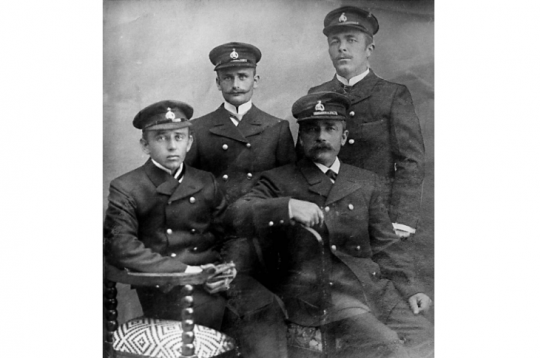

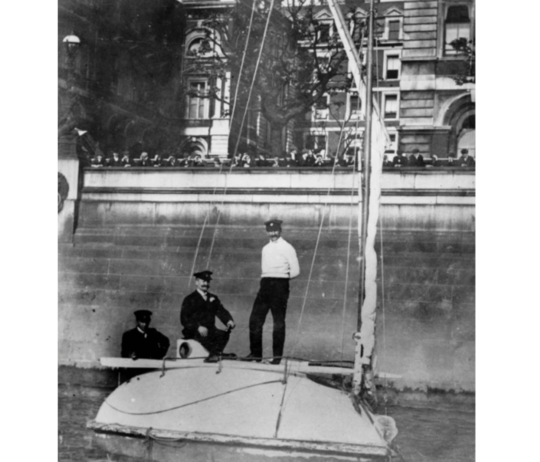

On August 7, 1904, Ole Brude and three companions, Karl Hagevik, Iver Thoresen and Lars Madsen, left Alesund for America. Packed with 6 months' provisions and rudimentary navigation instruments, they set out to test their revolutionary invention.

3 days after their departure, their arrival in Shetland caused a sensation. The canoe, nicknamed '' The bride's egg is not going unnoticed.

By demonstrating the canoe's buoyancy and validating its potential to save lives, the crew could have felt they had achieved their initial goal. However, Ole Brude had no intention of stopping there. The real challenge was the Atlantic crossing. His plan: to ensure maximum visibility by exhibiting his canoe at the World's Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, scheduled for April 30 to December 1, 1904. This event was of particular importance, as France was offering a prize of one million gold francs to the inventor presenting a truly innovative lifeboat model.

Motivated by this award, the crew set sail again. From the very first days at sea, they were confronted with difficult conditions. Armed with a sextant and compass, Captain Thoresen headed north to avoid the Gulf Stream current taking them back to Norway. In the north, the cold is intense. The small boat, tossed about by the swell, nevertheless continues to hold on. Sheltered from the spray and icy winds of the North Atlantic, the sailors realize the advantage of their steel capsule: they stay dry, an invaluable luxury for shipwrecked sailors.

On board, space is confined. 4 adults in just 14 square meters, light dimmed by oil lamps, and stale air inside. Every week, the situation deteriorates further. The inside of the egg begins to freeze, making the atmosphere even more miserable. One storm follows another. A violent hurricane and raging seas threaten their progress. The barometer continues to fall and the mast breaks, before finally being repaired at sea. " Storms rage with violent hailstorms. I sit with my heart in my throat for every sea that breaks over us. I'm afraid the mast will break again "wrote Captain Iver Thoresen in his diary.

More than 2 months have passed and there are still 2 months to go before the World's Fair closes. The ordeals are piling up. Brude, seriously injured after a fall into the sea, has no medication on board. Sanitary conditions were deplorable, and he suffered abdominal pains. The pump-action toilets quickly became overcrowded. " We're wet and freezing, so we're chattering our teeth. Everything's wet. Nowhere to go. Just stay quiet. Dark night outside "says Captain Thoresen, resigned to the scale of the difficulties.

For him, the journey becomes more and more exhausting. Hallucinations and exhaustion take over his mind. A newspaper with a brand-new team appears: Jim, Jack and Paddy. " Jim lifted the lid. The peas are alive and have all started to grow. (...) Paddy said there was liquid mercury in the jar. It made the peas jump. It made us laugh. We decided to let the peas jump overboard "he notes in his logbook. Thoresen, who may have been poisoned by canned food or mercury balls designed to keep clothing lice at bay, is the only person on board capable of precise navigation.

Finally, after 3 months of suffering and battling the elements, land appeared on the horizon. In December 1904, '' The bride's egg '' ran aground on the shores of Gloucester, north of Boston, Massachusetts. The 4 Norwegians have survived one of the most arduous crossings of the Atlantic. Their objective had been achieved: their lifeboat, tested in extreme conditions, had proved its strength and efficiency.

A limited impact but a pioneering idea

It was a radical turnaround. Staying at the fashionable Atlantic House hotel, Ole Brude and his crew spent several days as veritable superstars. They frequented elegant dinners, drank champagne and were admired by the ladies of high society.

The World's Fair was now over. The original goal of crossing the Atlantic in 3 months had been far exceeded: it had taken them 5. The prize of 40 million crowns was never awarded. Time passed and the hotel owner asked that the egg be removed, as it was not a marina.

Then one day, Ole Brude disappeared. The crew, penniless, was forced to leave the expenses to others. By way of consolation, Ole Brude had received a French vase, a paltry prize compared to the millions he hoped to win. Back in Alesund, he didn't give up. He founded the Bride's Lifeboat Company and obtained patents worldwide. Despite the media attention it had received, enclosed steel canoes were struggling to establish themselves. The marine industry remained attached to traditional models, and attitudes were slow to change. Ole Brude embarked on a tour of Europe to promote his concept.

It wasn't until several decades later that his idea was fully adopted. 22 sisterships were built, some of which saved lives during shipwrecks. During the First World War, for example, one of these boats saved 26 people after a German torpedo attack.

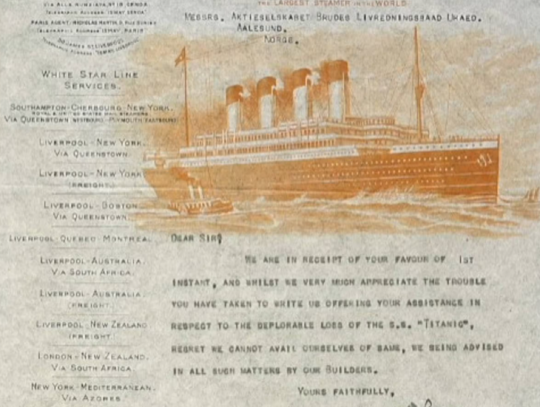

Following the sinking of the Titanic, which claimed 1,500 victims in 1912, the Brude company sent its condolences to the French people White Star Line while showing off his lifeboats. The response, while polite, was discouraging. The shipping company considered that the decision on lifeboats rested exclusively with the shipyards.

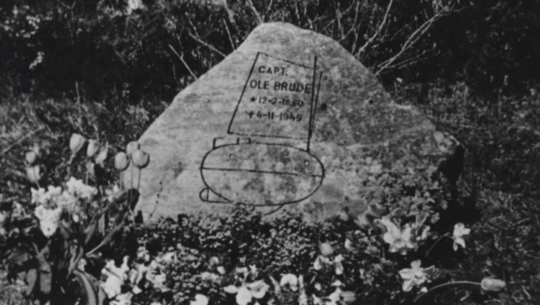

A replica of the Uræd is now on display in Alesund as a tribute to the ingenuity and courage of Brude and his crew. The town's museum also watches over his grave.

Although Brude's lifeboats didn't enjoy the success he had hoped for during his lifetime, it wasn't until 1978 that enclosed models became compulsory.

/

/