In June 1958, a crew of three men and one woman embarked on an unprecedented crossing of the Atlantic in a hydrogen balloon. An ambitious project that quickly turned into a 24-day struggle for survival after the gondola ditched. The result of the ingenuity of Scottish architect and navigator Colin Mudie, the gondola, converted into a boat, became a crucial element for the crew. Here is their story, based on the facts reported by Rosemary Mudie in Look and Learn a weekly newspaper published in 1965.

In the footsteps of the trade winds

The story of this extraordinary crossing begins when Colin Mudie, his wife Rosemary and their friend Bushy Eiloart discuss their previous transatlantic voyages over dinner. " Colin pointed out that all these trips would have been drier and much faster if we could have floated in a balloon thirty meters above the sea, with the trade winds carrying us directly to our destination." rosemary Mudie recalls. This dream of aerial escape soon became a concrete project. Colin Mudie, a man of many talents, is renowned for his ability to design racing machines and replicas of historic sailing ships. His first Atlantic crossing, in 1951 with his friend Patrick Ellam aboard the 19-foot cruiser Sopranino, had already made a lasting impression.

The team is soon reinforced by Bushy's 21-year-old son, Tim. They made contact with the department at Bristol University, renowned for its research into sounding balloons, and with Professor Powell, winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics. In the late 1950s, the goal of a balloon crossing became an opportunity to study the meteorological and aerological conditions of the high-altitude trade winds. London's Imperial College of Science also offered to lend essential measuring instruments to the expedition.

Innovative design

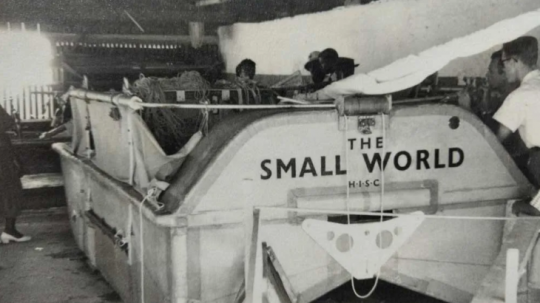

Colin Mudie devotes himself to the creation of a balloon with an impressive wingspan, measuring 14 meters in diameter and capable of holding 1,500 cubic meters of hydrogen.

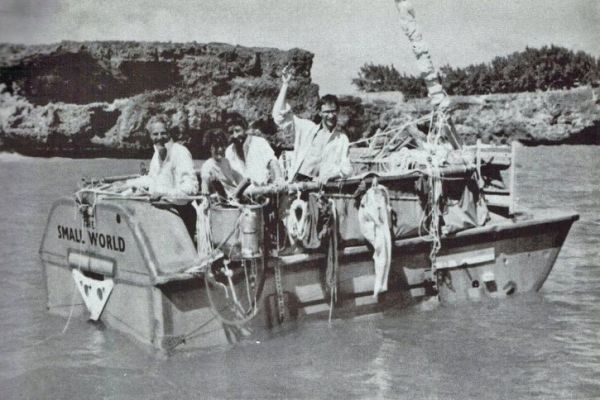

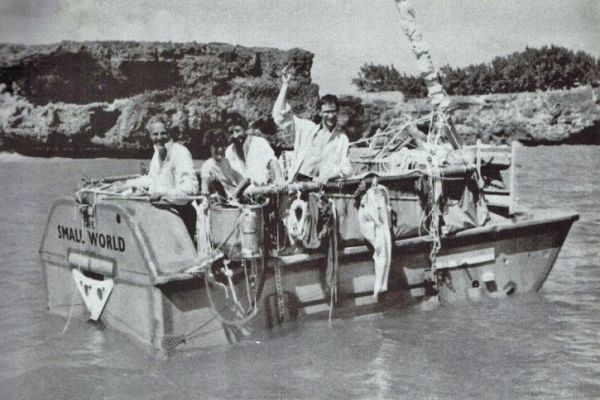

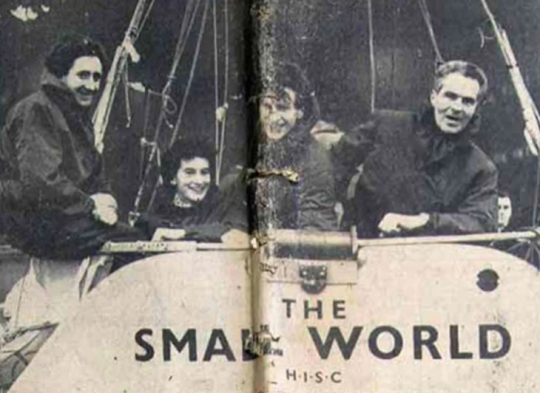

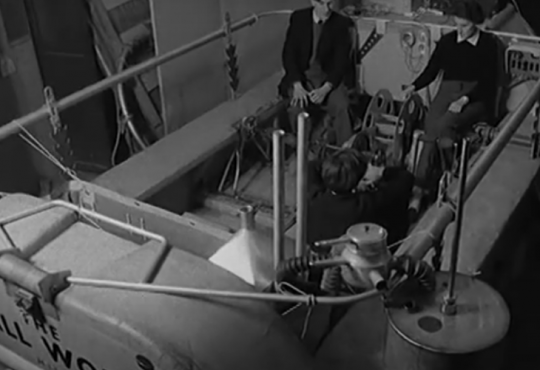

He also imagined a nacelle cleverly designed to transform into a sailboat in the event of an unexpected water landing.

The specialists recommend the use of modern materials for the envelope: Tergal fabric covered with Neoprene, guaranteeing robustness and lightness. Rosemary Mudie explains the difficulties inherent in this design: " In theory, and under stable conditions, our 53,000 cubic feet of hydrogen could lift 3,600 pounds. In practice, conditions are never stable, and you have to keep a constant eye on the altimeter. Heat can expand the gas and lift you up, or a thermal current can catch the balloon and lift it like a kite. To control ascent and descent, the pilot must drop ballast, usually sand, or let out gas ."

To avoid using sand as ballast, the team decided to recover seawater and also considered using calcium hydride to produce additional hydrogen. To increase lift, horizontal pedal propellers are added to propel the air downwards.

Finally, a braking device suspended under the basket and materialized by an 80-pound (approx. 36-kilogram) drag rope is integrated. Submerged in water, it increases resistance and relieves the load as a function of height, while providing additional support when the balloon is lifted above the sea.

Meticulous preparation

On December 12, 1958, the long-awaited moment arrived: the crew took off from Medano beach, Tenerife. At the controls, Captain Bushy Eiloart and his son Tim, who acted as radio operators and meteorologists, and the duo of designer-navigator Cohn Mudie and photographer Rosemary Mudie, set off on an unprecedented 3,600-mile crossing of the Atlantic, making Small World the first balloon to embark on such an east-west adventure. For nearly 3 years, they meticulously planned this expedition, learning how to build and pilot their own balloon, while ensuring that the design of the craft could safely accommodate the crew beyond all precedent. Bushy's efforts to secure British sponsorship finalized the preparations and brought the crossing project to life.

The Small World adventure marks the start of an extraordinary journey combining technical innovation and human daring. After years of preparation and a successful take-off from Tenerife, the crew set off across the Atlantic in their hydrogen balloon. But this ambitious project, supported by feats of engineering, soon came up against the whims of the sea and the elements. This was only the beginning of their epic journey. What follows, marked by an unexpected shipwreck, will reveal the crew's strength and ingenuity in the face of adversity. Find out how they fought for survival in the second part of this series.