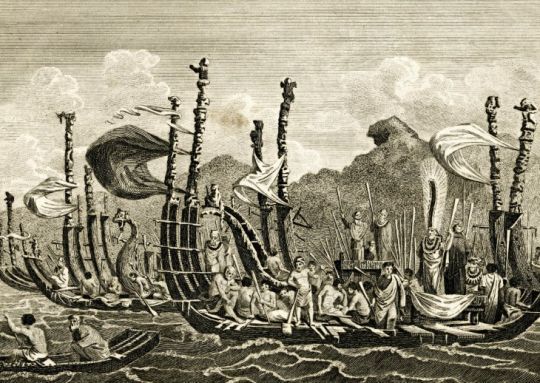

In Polynesia, the great pirogues, true masterpieces of marine carpentry, embodied a unique know-how combining art, technique and spirituality. Their construction, supervised by specialists known as tahu'a, was based on meticulous traditional practices and sacred rituals. Let's take a look at the complex methods and natural materials used to create these boats, as well as the social and cultural impact of their manufacture.

The sacred crafts of the tahu'a

The construction of the great Polynesian pirogues was orchestrated by the tahu'a these were craftsman-priests specializing in once-vital areas such as navigation, fishing and the healing of illness and injury.

Their know-how, transmitted orally in schools reserved for a social elite, was combined with an in-depth knowledge of materials and rituals. The tahu'a exercised their skills in marae sacred places dedicated to these constructions. Their technical expertise was inseparable from their ability to establish relationships with the deities and their mana, a spiritual force essential to the success of the project.

Over time, the memory of tahu'a has faded. Although the arrival of Christianity hastened their decline by gradually removing them from society, these major figures of the ancient Polynesian world, once the guardians of nautical knowledge and practices, remain part of the collective imagination.

Construction phases

The construction of a large pirogue followed a meticulous process. First, the master builder obtained permission to cut down the necessary trees, while securing the agreement of the deities through offerings. The trees were felled during the last lunar phase, to prevent putrefaction of the wood drained of its sap. The appearance of its discharge was then interpreted as an omen. The trunks were roughened in the forest to facilitate transport to the building site, then the wood was cut and shaped using traditional tools such as adzes and hardwood wedges.

The prepared parts were carefully transported, often by water to lighten the load. Final assembly of the parts took place in a coastal workshop, where carpenters secured the components with fiber ties and reinforced the hull with inner ribs. Finishing touches, such as the carving of the bow and stern ornaments, were carried out with precision using small adzes, as well as coral, ray or shark skin rasps.

Women and elders helped to make sails from pandanus leaves and ropes from the rot-proof fibers of coconut husk and purau underbark. Kilometers of rope were needed to assemble the pieces of the pirogue.

Paddles, rudders, bails and anchors were placed on deck, where a leaf-roofed cabin could also be found. The construction of a large pirogue thus mobilized the whole of Polynesian society, with everyone ensuring that every element was ready for the launch.

Appropriate use of traditional materials

Polynesian carpenters chose their materials with great precision, according to the specific requirements of each type of boat. For offshore pirogues, dense, hard woods were selected for their resistance to prolonged mechanical stress. Coastal craft, on the other hand, were crafted from softer woods suited to less demanding conditions.

Every part of the boat, from the floats to the crossbeams, was chosen according to rigorous criteria. Floats required light, buoyant woods, while crossbeams had to combine flexibility and lightness. Highly stressed components, such as outrigger posts, were made of dense, durable wood. Rigging spars had to be both elastic and light to optimize maneuverability.

Caulking and sealing were carried out using breadfruit latex or various resins, sometimes mixed with plant fibers. The construction of large Polynesian boats required impressive quantities of raw materials. A 33-meter war pirogue, for example, required the felling of 85 trees and the use of 9 km of plant fiber ties.

Plant fiber technology

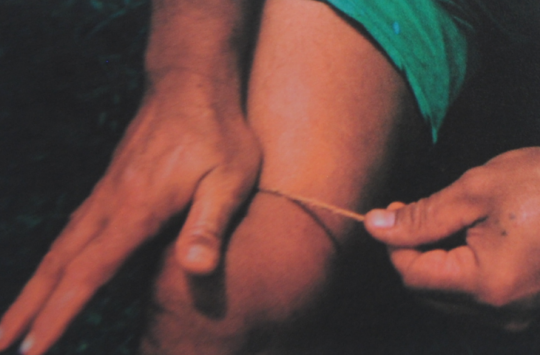

Plant fibers played a crucial role in the assembly of pirogues. Mainly derived from the mesocarp of the coconut, they were carefully processed to create strong, elastic ties. The manufacturing process was uniform throughout the archipelagos: after being cut into several pieces, deposited in a hole dug in the sand in an area submerged at high tide and covered with large stones, the mesocarps were retted for several days before being beaten to soften them. The fibers were then dried, spun and braided.

Other fibers, such as those from aerial roots, were used for specific bindings. Long fibers from the bast were preferred for large ropes, reducing the number of joints needed to make the ties. Bindings made from coir fibers or other natural materials such as feathers were essential to hold the pirogue's structure in place.

The construction of large Polynesian pirogues was thus deeply rooted in local culture and beliefs. The balance between traditional know-how, choice of materials and respect for religious rites illustrates the importance of this practice in Polynesian society. This complex, collective process, linking artisanal skills and community cohesion, testifies to the unique know-how and pervasive spirituality of Pacific Island marine carpentry. Even today, although techniques have evolved slightly from tradition, the great Polynesian pirogues continue to be built and sailed.

/

/