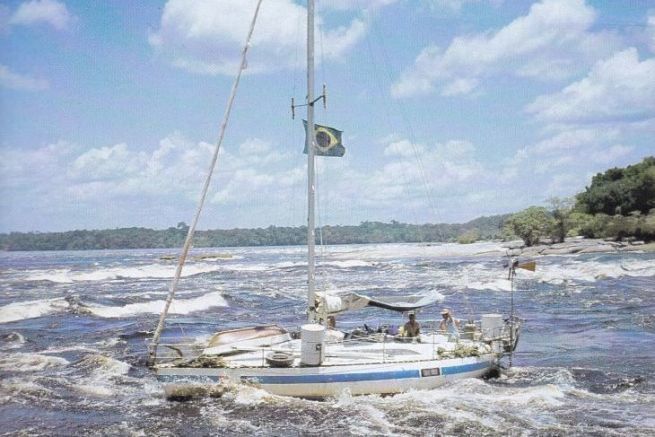

Jean-François Diné was the 1st yachtsman to link the Orinoco and Amazon rivers in South America in the 1980s, on a 10-meter sailboat built by his own hands. This impressive navigation involved crossing a series of rapids with his sailboat, crossing the territories of the Yanomami Indians on the borders of the Orinoco River, and getting lost in the labyrinth of sandbanks on the Rio Negro, a tributary of the Amazon. He tells us all about this dangerous and exciting experience.

Why did you decide to take up river navigation, and what specific features of your sailboat do you think made it easier to link the Orinoco and Amazon rivers?

In fact, there was no question of going to Amazonia in the first place. I'd cast off for a round-the-world trip, not to sail up rivers. I had prepared everything for it, I had bought all the maps of the Patagonian canals, the Pacific islands, the Indian Ocean... But my wife - well, my ex-wife - didn't like the sea. I thought she'd get used to it, but no, she never did. As I really didn't want to give up this project, which was an old childhood dream and for which I'd spent five years of my life to get the boat, I thought the solution would be to go up the rivers. We'd been down to the Mediterranean via the Seine, the Saône and the Rhône, and that hadn't scared her. Rivers don't move, the land is on either side, you drop anchor in the evening, and in the morning you've had a good night's sleep, and that suited her just fine. So we started out in West Africa, along the Gambia, Saloum and Casamance rivers, stopping off in villages... Everything was going well. The problem was that she vetoed the Patagonian canals outright. And I really didn't want to end up in a West Indian port after dreaming of a trip to the other side of the world... So, after an extended stopover in French Guiana to replenish the ship's stores, we stopped off on the Maroni River, in the Galibi village of Terre Rouge. The Amerindians are really lovely people. They accept us as we are, and are never judgmental. This stopover lasted several months. Then we headed back north with the idea of spending Carnival in Venezuela. We landed in a small bay not far from the port of Guiria, in the Gulf of Paria. The only way to navigate in those days was by sextant... We made friends with an old fisherman who invited us to his home. A large decorative map of Venezuela lined his wall. A strange detail appeared on this map: a small blue line between the Orinoco River and the Rio Negro, a tributary of the Amazon. The fisherman explained that this was a canal linking the two rivers, but was unable to give any further details. It was then that the idea for this journey was born...

For two weeks, I tried to gather information from the various authorities. But it was all a complete blur. No one could give me any valid information, except that there was an absolutely marvellous region, inhabited by people like no other, a sort of earthly paradise, and that this region was called the Orinoco-Amazon basin... This was the only clue we had as we set off on our adventure... I thought we'd find maps as we went along, but the further back we went, the less we found. In fact, there simply weren't any.

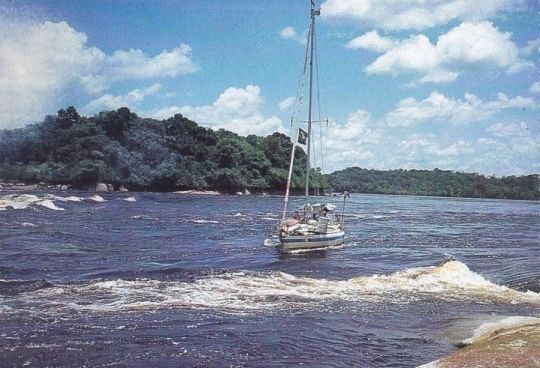

Can you tell us about the towing strategy you employed to avoid the waterfalls at Puerto Acucio and how it affected your progress?

There weren't many solutions. We had to find a fairly solid trailer, lower it deep enough, put the boat on it, pull it out of the water with two tractors, then take the boat to the other side of the rapids. It was two days of total stress. The trailer wheels were sinking into the sand, so we found a second tractor to mount it on the ramp, but the tow rope was rusted and fraying in places. I had to look for wooden wedges to place under the trailer's wheels as it went up, in case it broke.

Crossing Puerto Ayacuche was extremely difficult. The main avenue was lined with old trees whose branches formed a kind of canopy over the road, and we had to cut off any that refused to bend. We then had to pass under hundreds of electric wires, lifting them one by one with a wooden pike pole. One of them was ripped out anyway... The track through the forest was full of holes, and the driver was going much too fast. One of these holes was huge, and almost toppled the trailer and boat over... At one point, one of the national rangers escorting us let off a burst of gunfire into the forest...

The boat returned to the water without too much trouble. The mast was raised using a large branch from a tree overhanging the river.

We spent the night under this tree. The next morning, a snake was found sleeping in a ball on the deck of the boat, under the liferaft I'd had to move because of the mast. A very dangerous species that an Indian had to kill with an oar...

What was it like meeting the Yanomami Indians and discovering this remote Amazon region?

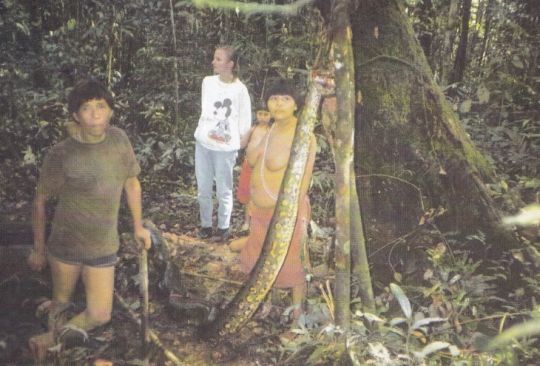

In fact, the village where we stopped was located on the Rio Siapa, a river flowing into the south of the famous natural channel linking the Orinoco and Rio Negro. When the water is high, you can go almost anywhere in this forest. There's depth everywhere; it's truly incredible.

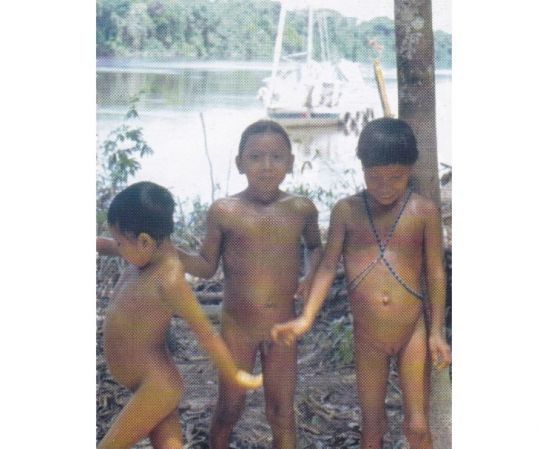

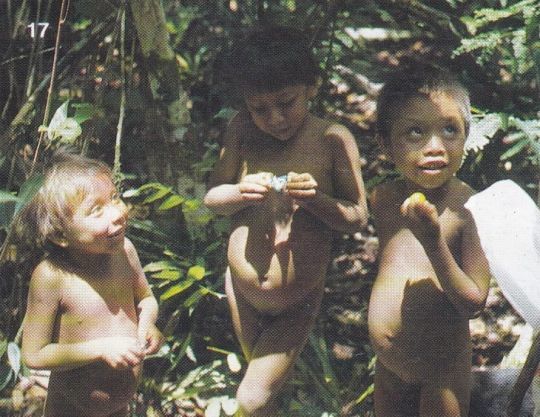

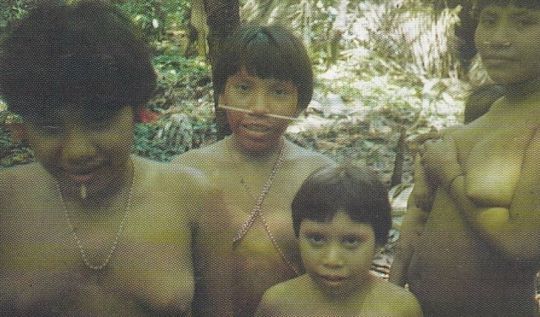

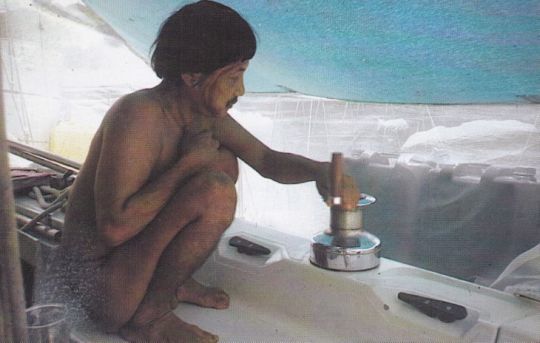

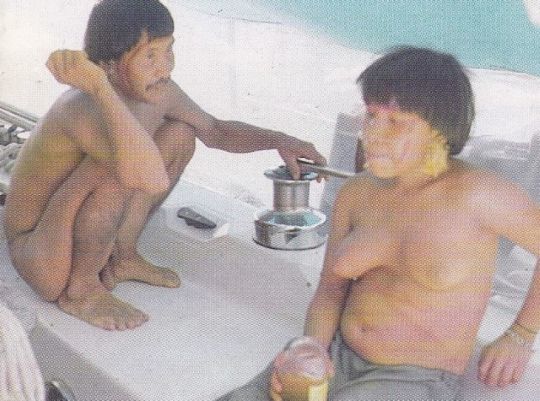

Of course, the Yanomamis had never even seen a sailboat. They didn't even know what an ocean was...

They have no television or anything to connect them to the world as it existed at the time. In fact, they have nothing - well, almost nothing. A hammock, a bow and arrow, a few kitchen utensils, a calabash, that's all.

Most of the time, they're naked. But clearly, they lack nothing. One thing is absolutely undeniable: they're happy! And they're certainly happier than we are, because they're always living in the moment. They don't constantly project themselves into the future, they don't anticipate as we do in our Western societies. When they eat a piece of fruit, they're happy to eat it and that's it. Really, they're happier than we are.

The thing that struck me most was that they don't welcome us, they integrate us directly. It's a very special culture, because you almost feel part of the tribe right away... It's really very pleasant.

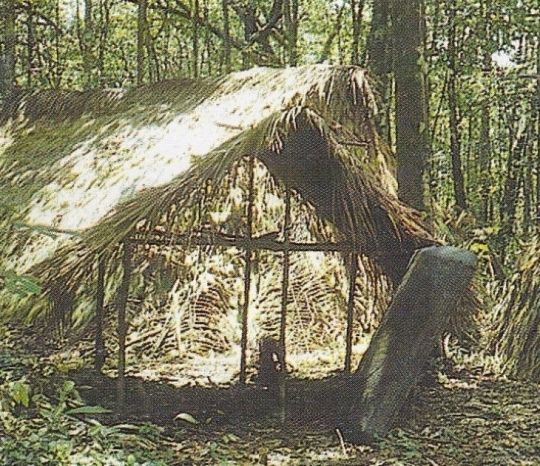

You can find many accounts of people who have lived with the Amerindians, and of course they accept you without any problem when you arrive. You arrive, you build your carbet, and you live with them. It's as simple as that. We could have stayed for a very long time if we'd wanted to. They asked us why we didn't build ourselves a carbet like they have.

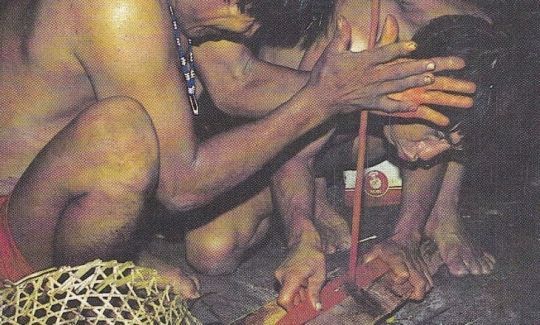

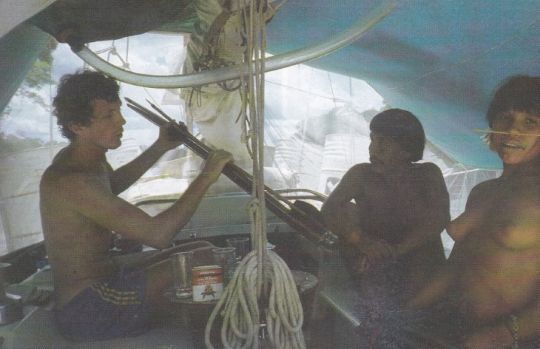

We were able to see everything that was going on. We got to know everything that interested us. We ate with them, under their carbets; they came on the boat. Every time, the men and women dressed up in beautiful paintings, it was really great.

Two of them spoke a little Spanish, which enabled us to create a sort of Yanomami-French lexicon, very succinct - drinking, eating, sleeping - but which enabled us to understand them and make ourselves understood. This was often accompanied by gestures, and even little drawings, but we were really able to communicate with them and understand a lot.

These are regions off-limits to tourists. At least when you've been there. I don't know what the current situation is. I hope it's still the case, because we really must preserve these incredible cultures... We did manage to get the permits, though. But we were warned that no matter what happened, nobody could intervene. We were shown the grave of a missionary "who'd had bad luck", and told that they could do whatever they wanted, because it was their home.

We stayed for almost two months, during which time the water level dropped considerably. At that point, we had no idea what navigation on the upper Rio Negro was like, so we had to leave, or risk being stranded until the water rose again next year. So we bid farewell to the village, pull up anchor and make for the rio Negro.

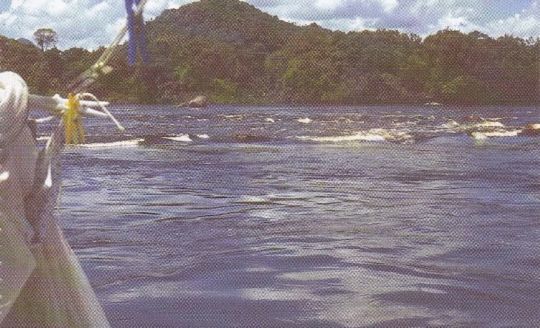

How did you tackle the rapids before reaching Santa Isabel, particularly in view of the challenges of the powerful currents and steep gradients on the river?

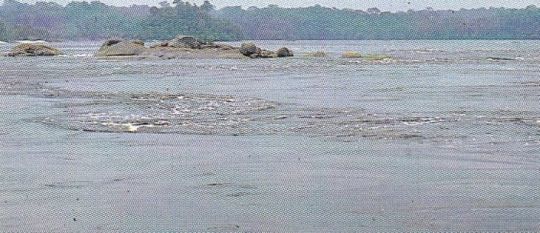

It was very complicated. Nobody had ever been there before with a boat like that, we didn't even know if it was possible, but we had to go anyway, because the water kept going down. It wasn't even certain that it would rise enough the following year to allow us to return via the other side. As we descended towards the Amazon, the rapids became more numerous and stronger. The water level is already too low. In some places, the river seems blocked by a rocky barrier.

But we have to keep going until we find the pass, because there's always a pass, even if it's not easy to find. These are moments of incredible stress. In places, the water speeds up. Huge eddies form under the hull.

Submerged reefs create huge turbulence in the current. It's like sailing in a gigantic boiling cauldron.

How far will it take us? We don't know; the only map we have is the one of Brazil on our little illustrated Larousse, a tiny blue line three centimetres long representing the thousand kilometers of the Rio Negro. We discover this river as we go along. Reverse gear is also lacking. The reversing gear broke down several months ago. And given our limited means, the faulty part could not be replaced. As a result, each time the water accelerates and we pass certain rapids, we feel catapulted, with nothing to do but try to keep the helm in the direction we feel is best.

The climax of this hellish navigation is reached at San Gabriel. A three-meter drop over a distance of fifty meters seems to put an end to this insane journey. We'll never get over it, we think... Well, we'll have to, as going back is totally impossible. Fortunately, we find an Indian who says he knows a way through. He'd already done it with his pirogue. I ask him to take the helm. After a dozen or so signatures in that Catholic way, we're off... It was a moment of incredible stress. But the boat went through.

One of the impressions that will stay with me for the rest of my life is the one that animated my inner self every morning, when I had to pull up the anchor to continue. It was like a ball forming in my intestines... Would the boat still be afloat at the end of the day? In the morning, navigation was still very difficult as the Rio Negro descended to the south-east. The sun reflected off the water and dazzled us. We had to go very slowly. The engine was always almost idling. We were making very slow progress. And then, when I dropped anchor after a day of slaloming through the rocks, the feeling was one of intense relief, as if I'd reached my goal. The boat was still afloat, there had been no problems despite the difficulties. I think that's how soldiers must feel after a day's fighting. We're still here, and now we've got the whole night during which nothing can happen. You just don't see things the same way when you're going through something like that.

What were the main difficulties encountered on the Rio Negro in terms of sandbanks, and what solutions did you find to overcome the frequent groundings of your yacht?

It was very complicated. Once past the rapids, it seemed as if the biggest difficulties had finally been overcome. The rocks have effectively disappeared, and there are no more rapids or flush reefs.

The river widens, and islands gradually appear - dozens, then hundreds of islands covered in lush vegetation. In places, the river is over 15 km wide.

Then another difficulty looms, something even more stressful and unheard-of than the rapids: the sandbanks...

What the river gains in width, it loses in depth. The result is a veritable labyrinth, a kind of circuit where it's easy to get in, but impossible to get out. In some places, it's as if you're surrounded by shoals. Sandbanks are everywhere, to port, to starboard, and even behind, to the point where you wonder how you got here. It's a real ordeal. We run aground dozens of times, forcing me to unhitch the boat on an anchor, which I set down in the dinghy, as the reverse gear still doesn't work.

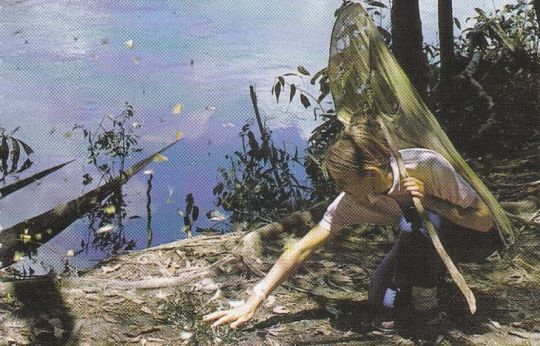

At some point, we resign ourselves to waiting for someone to come along. Someone who could act as a guide, even if it meant paying out some of our precious dollars. And so it was that we waited for more than eight days near a small island, eight days without seeing a soul. We then perfected a technique that should enable us to make progress. I take the boat out to probe the seabed until I find a passage of sufficient depth, whereupon we agree on signals with Claudette, who is waiting for me at the boat. And so we continue on our way. The technique is good, but painful and slow. It sometimes takes me hours to find the right spot, hours of rowing while throwing the lead under the hot equatorial sun.

We covered more than fifty kilometers in this way, me rowing like the old galley slaves, Claudette going round in circles waiting for my signal, but there's still the equivalent of half of France to go...

I'm fed up, I want to drop everything and give up. I've never felt so discouraged since the start of this adventure. What if we met someone? But we seem to be the only ones in this hellish maze, this diabolical land of half water, half sand, lost in the heart of the Amazon. Then something unexpected happens. After dropping anchor to refloat the yacht, I let myself drift aboard my little wooden boat. At this point, I realize that the current is not flowing over the sandbanks, but rather obediently around them... So I had an idea. We disengage the boat's engine and slowly let ourselves be carried away. As I'd predicted, the sailboat begins to lace the surface, as if guided by an invisible hand. It simply follows the current as it skirts the shallows. This is how we sail for several days, letting Mother Nature gently guide us.

Gradually, as the shallows diminish and the depths increase, we reach the small town of Barcelos. The rest of the way is a formality. Depth is everywhere now. In just a few days, we reach Manaus, the capital of the forest! The descent of the Amazon poses no particular problems.

Whenever possible, we take the rios transversales, small rivers that flow around huge chunks of land. The smallness of these waterways, often no wider than the Canal de Bourgogne or the Canal du Nivernais, brings out the beauty of this lush vegetation. At the end of the year, after more than 1500 km down the Amazon, we drop anchor opposite the Belem yacht club. The tour of the Guyana Plateau is complete!

What lessons have you learned from navigating in these extremely difficult conditions, and what advice would you give to other sailors contemplating similar expeditions on rivers in remote areas?

It's very difficult to give advice, because if I'd known what was waiting for me, would I really have gone? I know how it all ended, and I'm now very happy to have made the journey. But when you're there, you don't know how it's going to end, and I can guarantee you that in some places you're squeezing your buttocks almost all the time...

If you're really planning a trip like this, and you go knowing exactly what you're in for, then maybe there's a bit of recklessness involved after all. When we went, we didn't know. Which might have led you to think that everything could have been as easy as sailing up the Gambia, for example. My boat was totally unprepared for such navigation. I had a two-bladed propeller for sailing up the Orinoco currents... On several occasions, I had to enlist the help of the locals, who put their motorized pirogues alongside the sailboat and pushed me to get past certain accelerations in the water.

I had no reverse gear... The reverser had broken down when we were in Africa. But when you get used to it, it's just a detail. To stop, you either face the current, or drop anchor altogether. I had all the maps of the Patagonian canals in my trunks, and I found myself in the middle of the Amazon with only the map of Brazil in the Petit Larousse Illustré, because there were no maps of these places. But it's very easy to learn to read the surface of the water, and to discover the traps without needing a map. When there's a current, the slightest rock creates turbulence on the surface. These vary according to the depth of the rock. When you have no choice, you adapt. You can't do it any other way. We know, for example, that when there's a current and the surface is smooth, there's depth. When there's a whirlpool, there's also depth. We also know not to get too close to the bank inside meanders... In a very short time, you could almost draw up a map just by looking at the bottom.

On the other hand, the sandbanks were more complicated. In the rapids, it's hit or miss, but you know right away. On the sandbanks, you feel like you're stuck in something that sometimes seems really huge. And above all, you meet absolutely no one...

We had to figure it out for ourselves. In fact, the solution was simple, but we still had to think about it.

What motivated your decision to set up a cultural center after your sailing days, and can you tell us more about this particular project?

I hadn't really set out to write a book, but on the way back the question arose: if I was going to write a book in my life, it had to be now or never. So I wrote not one, but three books covering the five and a half years of my trip. I had resumed my job as a gendarme, but my hierarchy was very complacent, and systematically arranged for me to be granted leave when I needed to go and sign documents.

But I was still hungry after that first trip, because even though it had been extraordinary, I still hadn't fulfilled my childhood dream of sailing around the world... A by dint of selling books, there came a time when finances were no longer an issue. So I bought myself a new boat, wrote my letter of resignation, and set sail again, this time with my two children. The voyage lasted seven years, until Victor, the elder of the two, had to return to France for higher education. I couldn't leave him alone, so I came back too.

I've been on land for a few years now, and the urge to leave is still there. Except that I've embarked on another, very special project: to create a kind of cultural center on a property not far from Paimpol, in Quemper-Guezennec, the birthplace of the navigator Paul-Antoine Fleurio de Langle, commander of the Astrolabe who took part in the La Pérouse expedition. The place will be called the "Milin Kemper" center, which means "the mill of the confluence" in Breton, in reference to the superb mill there. I'm not there yet, but it won't be long.

If you're on a boat and happen to be passing through on your travels, there's a small marina in Pontrieux that's exactly 2,500 meters away on foot. So don't hesitate to come and moor your boat there, and pay us a visit when the center is up and running (most likely after the summer, as there'll be plenty of work to do once we've got the keys). There will also be a vegan restaurant. You'll be able to discover, among other things, a mini exhibition about this Orinoco-Amazon trip, as well as all the rest of my books of course - I've just released my ninth.

To get to Pontrieux, you'll have to travel up the Trieux. Watch out for the last three meanders if you try to go upstream at mid-tide. You can end up stuck in the mud after the mouth of the Leff. If this happens to you, just wait for the water to rise...

/

/