Terrible testimonies to suspended routes and human tragedies, or objects of passionate quests for fabulous cargoes, shipwrecks are unparalleled diving sites. In this sunken ecosystem, the Centre d'Études, de Recherche et d'Expertise Sous-marines (CERES), founded by Bertrand Sciboz, reveals a singular face of underwater exploration. We take a look at the challenges faced by a company tasked with locating, salvaging and preserving shipwrecks.

Creating a database

For many years, Bertrand Sciboz, scuba diver and underwater research expert, has been committed to locating shipwrecks to ensure their preservation and survival. Driven by his commitment, he looks back at the genesis of his company: i created two databases. One, geographical, which I sold to most French and European fishermen in the early 2000s, who were looking for wrecks for the fish they contained. The other, produced in Microsoft Access format, would nowadays resemble Internet data. The latter was to be used by government departments and was, in a way, requisitioned for me by the Ministry of Culture. I then authorized several amateur shipwreck-finding associations to use and exploit it

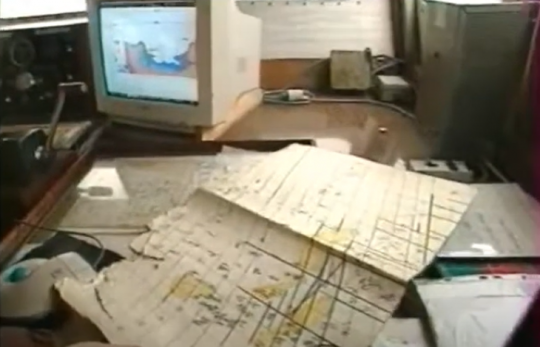

In the course of his fishing activities at Saint-Vast-La-Hougue in Normandy, Bertrand Sciboz set up a company specializing in underwater work. By hauling up trawls from the seabed, at the request of fishermen, he not only identifies his own wreck sites, but also discovers new ones. His approach consists of sketching freehand on extensive maps the points of known wrecks, as well as the coordinates of hooks entrusted to him by other fishermen. This embryonic database, initially based on informal exchanges between sailors, evolved with the abandonment of paper and the rise of navigation software in the mid-90s. Cap Info was born.

The company then reoriented its objectives towards reasoned inventories and heritage protection. Initially rooted in the Bay of the Seine, the database soon extended its footprint to the whole of France's western coastline, from northern Spain to Belgium, as well as to the Irish and Scottish seas, the Baltic and the Mediterranean.

By encouraging today's navigators to evolve in complete safety, these databases have become crucial players in both economic and preventive terms.

Wrecks hinder navigation

Wrecks are not only abundant fishing grounds, but also formidable traps for fishermen's nets. How many fishing vessels have sunk due to a hook holding back their trawl? The declaration of a wreck by a fisherman is often synonymous with the loss of his equipment, a reality well known to Affaires Maritimes and DRASSM, the Department of Subaquatic and Underwater Archaeological Research.

Contemporary shipwrecks, due to their size and the use of metallic materials, create underwater obstacles of a very different scale to the modest mounds of wooden wrecks, buried under sand and mud. While the campaigns run by SHOM - the French Navy's hydrographic and oceanographic service - focus primarily on locating wrecks that hinder navigation, Cap Info takes every single hook point into account from the outset, carrying out systematic identification. This enables the discovery of old wooden wrecks from the 20th century, facilitating the study and preservation of these precious elements of nautical heritage.

The use of state-of-the-art equipment

Founded in 1994, Cap Info rapidly evolved into CERES, Centre d'Études, de Recherche et d'Expertise Sous-marines. Specializing in the fields of survey and salvage, the company is involved in a wide range of activities, including the search for submerged objects, the detection of explosives, underwater investigations, as well as the refloating and dismantling of wrecks, including waste sorting and disposal.

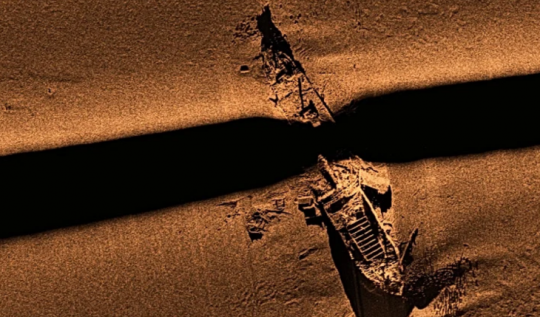

Based in Montfarville, Normandy, CERES has favored the use of multibeam echosounders from the outset, investing in an Edgetech dual-frequency sidescan sonar system. This device operates in a range of 300 to 600 kHz, at a speed of 8 knots, with a range of 500 meters on each side. At the same time, CERES is also acquiring a very high-frequency sonar (1250 kHz), enabling direct identification.

The acoustic imagery obtained provides a representation of the reflectivity of the bottom along the swath and, above all, of the presence of irregularities or small obstacles which are seen by the signal.

In France, Bertrand Sciboz and his team work aboard a catamaran specially designed and adapted for this type of mission. The CERES motorboat offers the possibility of rapid, one-off on-site interventions, as well as more complex, long-term operations. This feature becomes essential in areas subject to swell and wind, where responsiveness plays a crucial role. It is imperative to optimize the use of meteorological windows, particularly during geophysical and geotechnical studies, where the quality of results depends directly on sea conditions.

In addition, the Pioner Multi is a utility boat that enables the CERES team to respond to missions where the water height, proximity to the coastline and space available in the work area make it impossible to mobilize the catamaran. Particularly stable, the Sirius II enables us to carry out all kinds of oceanographic campaigns, as well as mobilizing divers easily thanks to the installation of a bow ramp.

Methods adapted to the type of wreck

When it comes to refloating ships, the approach adopted depends closely on the specific nature of the wrecks in question. Three distinct strategies are employed to accomplish this complex task. In the first instance, the use of balloons is an ingenious method, offering an effective flotation solution for raising the vessel to the surface of turbulent waters. Another alternative is to use a grab specially equipped with cameras and spotlights, acting like a giant sugar tong. This technique was originally designed to extract valuables such as ingots or metal bars from the holds of shipwrecks. A third strategy revolves around the use of an imposing barge equipped with a crane. This latter approach enables refloating operations to be tackled with power and precision, guaranteeing efficient intervention in often complex conditions.

On September 5, 2015, the Marie Madeleine cutter ran aground in the vicinity of the Saint Marcouf islands in Normandy. On September 20, 2015, Bertrand Sciboz's team organized a refloating operation that enabled this sailing ship, listed as a historic monument since 1984, to be put in dry dock to assess the extent of the damage.

Refloating wrecks, but not only...

Among the riches of New Caledonia's coral reefs, a large part of which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, lie hundreds of forgotten mines...

In 2008, Bertrand Sciboz, expert witness for the Caen Court of Appeal, published a disturbing report stating that in 1942, the Americans, fearing a new Japanese attack, had commissioned British ships, mainly Australian, to mine the various access points to the Pacific atolls and islands, considered as potential forward bases for the enemy. Thanks to its high-tech equipment, CERES was sent to Nouméa lagoon to search for the remains of anti-submarine mines that had remained there since the Second World War.

In 2009, an international demining operation involved 1,600 mines. Although most of their electrical firing systems are considered inoperative, each one nevertheless contains 300 kg of TNT, with fuses and detonators. In some parts of the lagoon, where the water is less oxygenated and the currents less violent, the mines are particularly well preserved, suggesting a virtually intact mechanism inside.

Environmental risk management

Bertrand Sciboz points out that there are two main environmental risks associated with salvage operations. The first concerns the fuels present in the wreck, while the second is linked to the potential explosives present in many wrecks and underwater artifacts, often inherited from conflicts, as observed during operations in New Caledonia.

When CERES was originally founded, its primary objective was the search for shipwrecks, both contemporary and ancient. Gradually, the company broadened its activities to include hydrography, ocean clean-up, mapping and seabed monitoring.

A significant example of CERES' involvement in environmental management is illustrated by the sinking of the Erika, a tanker carrying 31,000 tonnes of fuel oil which caused one of the biggest oil spills in French history in 1999, off the coast of Brittany. In this context, CERES provided detailed mapping of the area to facilitate the intervention of pumping boats, in collaboration with the BEA, Bureau Enquêtes et Accidents en mer.

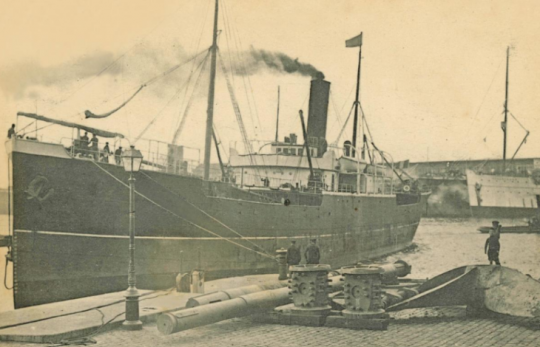

Treasure hunter

During his missions in search of high-value wrecks, Bertrand Sciboz confides that he has uncovered cargoes of non-ferrous metals in wrecks such as the three-masted barque Eugene Pergeline in southern Ireland and the three-masted freighter Barsac in the English Channel, both containing nickel. Loads of copper, tin and lead, as well as silver and gold, have also been extracted during specific expeditions.

"The underlying motivations are purely pragmatic and mercantile in terms of purpose." explains Bertrand Sciboz. "Although many people refer to archaeology and history, the reality lies essentially in the quest for treasures of financial value" .

Between heritage and pragmatism

Bertrand Sciboz is critical of the prospect of salvaging certain wrecks. from my point of view, it makes little sense to try to preserve wrecks that are doomed to disappear sooner or later'' he asserts. Taking the example of the D-Day wrecks, frequented by only a few divers, he questions the efforts made to protect them, deeming them disproportionate to their potential usefulness. in addition, you have to bear in mind that there are hundreds of wrecks made of different materials, which are also important fish stocks. As a result, fishermen contribute to their levelling by tapping into them.''

/

/