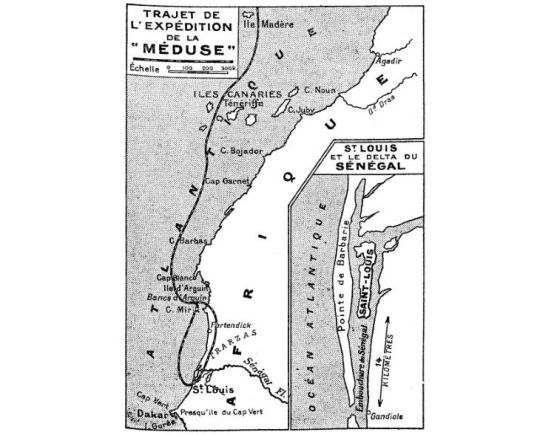

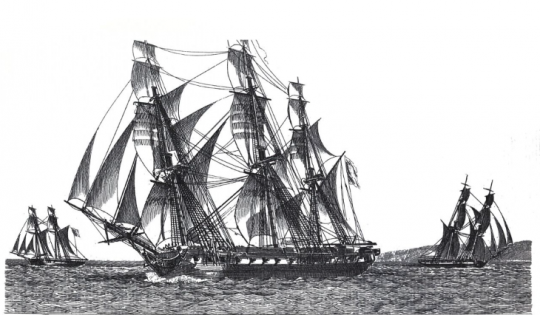

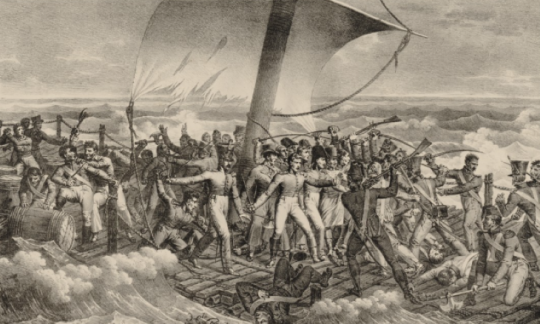

In the 19th century, a flotilla was mobilized to transport civil servants and military personnel to the colony of Saint-Louis in Senegal. Among the four ships assigned to this mission, the frigate La Méduse was at the center of a significant nautical episode. On July 2, 1816, grounded on the Banc d'Arguin, off what is now Mauritania, she became the scene of a struggle for survival involving almost 150 passengers. The makeshift raft that was built inspired Géricault's famous painting, "The Raft of the Medusa on display at the Musée du Louvre in Paris.

Shipment launch

In 1816, Louis XVIII, eager to recover the French trading posts in Senegal, sent a flotilla to re-establish the French presence. On June 17, 1816, under the command of Hugues Duroy de Chaumareys, the frigate La Méduse, armed as a 14-gun flûte, the gabare La Loire, the corvette L'Écho and the brig L'Argus left the harbor of Ile d'Aix. On board, a motley crew including engineers, a senior naval commissioner, an apostolic prefect, teachers, surgeons, pharmacists, workers, women, children and others, form a varied contingent destined to establish a new colony. Colonel Schmaltz, newly appointed governor of the colony of Senegal, was one of the passengers aboard the Méduse. Large quantities of equipment are taken on board.

Navigating by trial and error

Captain Hugues Duroy de Chaumareys, 53, hadn't set foot on a ship for 25 years. The first difficulties in leaving the Antioch Channel bear witness to this. Pressed by the imperatives of Mr Schmatlz, who wanted to reach Senegal quickly before the unfavorable season, the captain decided to take advantage of the Portuguese trade winds, which would hit him as soon as he rounded Cape Finisterre. La Méduse outpaced the other ships, which were supposed to be sailing in an orderly fashion.

On approaching Madeira, the ship plodded along all night, fearing the Eight Rocks reported in the area. Although she clumsily avoided these dangers, by morning La Méduse was 30 leagues too far east of the expected island. Chaumareys declares that the currents in the Strait of Gibraltar had thrown the frigate violently off course. Similarly, the charts contained in the French Hydrography, which had been placed at his disposal, as well as the marine watch, were, he would later say, defective.

Captain's negligence

Several episodes already testify to the lack of rigor on board La Méduse: a fifteen-year-old ship's boy disappears at sea while observing the porpoises' somersaults, while a fire, resulting from the baker's carelessness, breaks out on board. After Tenerife, the flotilla had to contend with frequent storms and currents that pushed La Méduse dangerously close to the coast. Despite the need to steer westward, Captain Chaumareys stubbornly persisted in a series of regrettable decisions and insisted on approaching the shore.

The threat of shipwreck

At the sight of the African coast, some, already familiar with these waters, feared they would run aground on the breakers, but the captain pretended not to hear them. Approaching Cape Blanc and the shores of the Sahara, the Echo, which has taken the lead of the flotilla, lights a lantern on its mizzenmast and launches rockets to signal a perilous course.

After several soundings, Captain Chaumareys assured us that he had crossed the Banc d'Arguin off Mauritania without a hitch, encouraging the crew to celebrate the Tropique's christening and have fun all morning.

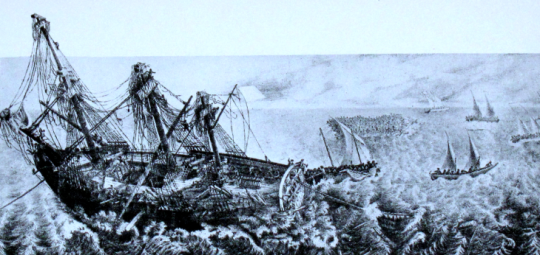

A final check of the borehole reveals a worrying depth of 18 fathoms, or around 33 metres. With each new throw, the situation becomes more urgent. Panic grips the crew, despite the captain's orders to hug the wind. Three jolts later, the ship came to an abrupt halt with a cracking hull. The frigate ran aground in less than 5 meters of water on July 2, a dozen leagues off the coast - 48 km.

Building the "machine

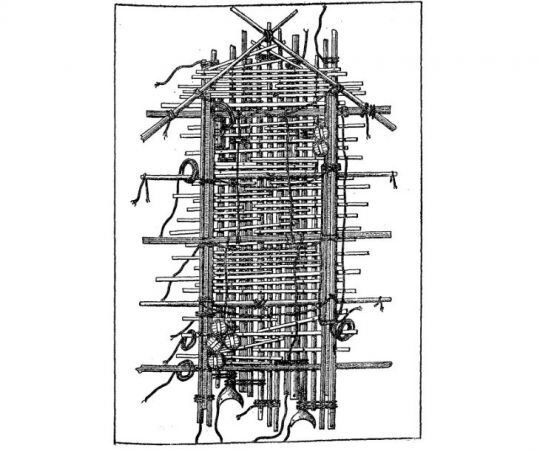

La Méduse hits the bottom at high tide, but suffers no serious damage. Attempts to refloat the ship failed, despite the persistent hopes of the crew. Faced with this impasse, Colonel Schmaltz sketched out a plan for a raft capable of carrying the men and provisions that could not be distributed among the longboats.

Considerable effort goes into building a wooden raft measuring twenty meters long and six meters wide, commonly known as the "machine". It is assembled from La Méduse's jib masts, yards, twin stays and boom. Securely fastened timbers extend between these elements, to which planks are nailed to form a kind of rail. On either side, a small forty-centimeter boom serves as a guard rail, reinforced by planks fixed askew, projecting three meters beyond each side. At the bow, a point is fashioned from two parrot yards, and in anticipation of the wind, a parakeet cockatoo and a large cockatoo are placed on the raft.

Forced abandonment

After a period of immobilization, a violent storm shook the Méduse, opening breaches in the hull and breaking her keel. In these critical conditions, it was time to leave the ship.

The six longboats are reserved for the privileged few, including the governor, his family, the colony staff, the commandant and the officers. The raft, on the other hand, is intended for the majority of soldiers and junior officers.

Hasty preparations

At departure time, an atmosphere of panic reigns among the sailors. The focus seems to be more on looting passengers' belongings than on making the necessary preparations for the crossing: passengers pile on five or six shirts, pull on several pairs of pants and jackets, and stuff several handkerchiefs into their pockets. Others, in desperation, drink to excess. Despite the preparations made the day before, there was still a great deal of unrest. The supply of food, ammunition and necessary instruments was neglected, with the exception of the raft, which was well stocked with drinks and contained the colony's fund.

When the departure signal is given, everyone rushes off La Méduse in a veritable shambles, forming human bunches on the ship's ladders, or rushing overboard via ends. Although some fall overboard, none of the 147 men on board drowns.

The promise of help

No sooner had the convoy set sail than the overloaded raft was taking on water and struggling to make headway. Two hours later, the mooring lines connecting it to the canoes broke. They were not replaced. Captain Chaumareys promised to send help to the unfortunates heading out to sea.

The disturbing absence of the Medusa

Arriving respectively on July 6 and 7 at Saint-Louis, a miserable town nestled on a sandbank formed by the Senegal River, the Echo and Argus were surprised by the absence of the Méduse at the landing. The situation was a cause for concern.

As for the Méduse's crew, some of the longboats made it to the coast: some men tried their luck in the desert, overwhelmed by thirst, walking and the hostility of the Bedouins they met. They are rescued after a fortnight's wandering. Meanwhile, other boats remained at sea and managed to reach Saint-Louis in four days. Among the occupants of these boats were Commandant Chaumareys and Colonel Schmaltz, bringing with them the first news of the Méduse tragedy.

The beginning of the ordeal

Meanwhile, 4 officers, 120 soldiers, 15 sailors and 8 civilians, including one woman, were still roaming the ocean. With no officer from La Méduse left to take command, the organization of the shipwrecked crew was left to chance. Pieces of wood, too long because they protrude to port and starboard, keep the raft askew, hindering any progress towards land, even though it is close at hand.

Cookie supplies ran out on the first day, intensifying tensions on board. One of the survivors, surgeon Jean Baptiste Henri Savigny, will testify in Le naufrage de la Méduse, Report on the sinking of the frigate La Méduse written with Alexandre Corréard original text republished by Folio : ''Those who survived were in the most deplorable condition; the sea water had removed the epidermis from our lower extremities; we were covered in bruises or wounds which, irritated by the sea water, caused us to cry out at every moment. [...] A burning thirst, redoubled by the rays of a scorching sun, devoured us; it was such that our parched lips drank greedily of the urine that we had cooled in small vases

The deplorable conditions quickly give rise to hallucinations and mirages. Disappearances at sea and suicides follow one another. A bloody battle breaks out, claiming 65 victims aboard the raft.

The barbarity of survival

Starving and thirsty, the survivors try in vain to catch flying fish and harpoon sharks with a bayonet twisted for the purpose. Exhaustion drives some castaways to gnaw through ropes, belts and even hats. In the face of despair, all end up indulging in cannibalism, cooking the flesh of the dead in an improvised hearth before finally eating it raw.

The crew shows no mercy when two soldiers are caught behind a wine barrel they've pierced and drank from with a blowtorch. Sentenced to death, they are thrown into the water.

Further rebellions broke out, drastically reducing the crew. By July 10, some 30 passengers were still alive, half in agony. In a macabre act, the sick are eliminated to double the ration of the strongest fish caught.

The last moments

On July 16, the castaways, exhausted and desperate, joined forces in a last-ditch effort to build a smaller, lighter raft. However, the attempt to launch the raft turned tragic when it capsized. The last survivors resign themselves to their fate.

The next day, a ship appears on the horizon.

Géricault's painting bears witness to the unspeakable horror experienced by those shipwrecked on the Méduse. It was these last moments on the raft that Géricault chose to depict in his painting.

On July 17, the Argus managed to rescue the survivors of the Méduse raft: only 15 men out of the 147 passengers initially on board. 5 of them died on the way.

An international scandal

Repatriated to France aboard the Loire in November, Captain Chaumareys found himself at the heart of a resounding trial. On February 24, 1817, the military tribunal on board the flagship anchored in the Charente River delivered its verdict. Chaumareys was sentenced to three years' imprisonment and disbarred from the Navy.

The uproar that followed this tragedy turned into scathing criticism of a navy perceived as archaic and dominated by royalists, reluctant to incorporate the advances made by the Empire in the naval field.

Géricault's research

Two years after the trial, the young painter Géricault immersed himself deeply in his subject, delving into the poignant writings of two survivors. He explored hospitals and morgues, scrutinizing the dying and the dead. In his quest for the truth, Géricault even reconstructs a raft at sea, observing its precise roll over the waves to capture the authenticity of the horror experienced.

The surprise of the last survivors

On August 25, 52 days after the sinking, the frigate Colomba arrived near the wreck of La Méduse. Against all odds, three survivors emerged, who had chosen to remain on board. In order to survive, they had set up separate markers: the first on the foremast, the second on the mainmast, the third on the mizzenmast, and left their refuge only to salvage the supplies: brandy, tallow, salted bacon, plums... that La Méduse still held. Twelve of their companions who remained on the frigate had attempted to build a raft, but the fate of this attempt remains unknown; it was undoubtedly fatal.

Rediscovery of the wreck

On December 4, 1980, the Groupe pour la recherche, l'identification et l'exploration de l'épave de la Méduse, or GRIEEM, team identified the metallic remains of the Méduse wreck under five meters of water, based on surveys carried out by the French Navy's Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service (SHOM). Part of the ship's equipment, including a cannon, is recovered and exhibited at the National Museum in Nouakchott, Mauritania.

The Raft of the Medusa has been reconstructed and can now be seen in the courtyard of the Musée de la Marine in Rochefort.

To understand the living conditions on board, you have to imagine 150 people on the boat.

Géricault's work is a realistic depiction of the story of the shipwrecked crew of the frigate La Méduse. A canvas that immortalizes and uncompromisingly exposes the brutality and despair of these men who fought for their lives.

/

/