An engine produces heat that needs to be regulated to allow the mechanics to operate at their ideal temperature, this is the mission of the cooling system. Whatever the engine, the principle is the same: the mechanical parts are brought into contact with a cooler element, air or water, to cool them down. Except on very small outboards, the air cooling is little used. In fact, water is abundant around the boat and its coolness makes that the builders have privileged its use to cool the engines.

Different exchange systems

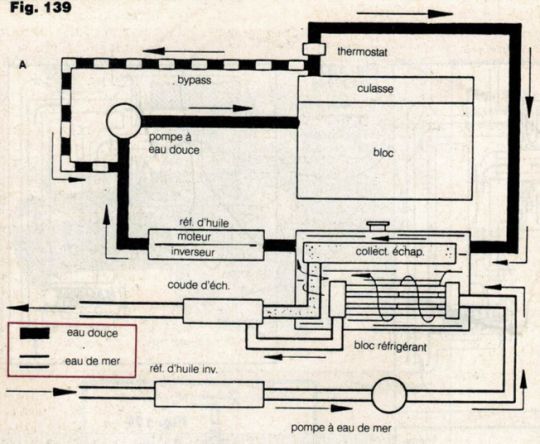

Water-cooled inboard engines most often use a indirect" cooling with temperature exchanger . They have a so-called internal circuit in which the coolant circulates, the exchange with the water being done externally to the engine.

In the case of a keel cooling (keel cooling), the liquid circulates in a bundle of tubes placed under the hull or in a tank in contact with it. It cools down in contact with the surrounding water. This system is efficient, especially in water loaded with alluvium, but the contact surface must be large to allow a good exchange, which reserves it for large units.

The temperature control can also be at direct cooling . In this case, the sea water circulates directly in the engine block and the cylinder head before being rejected. This system is archaic, as the thermal regulation depends too much on the temperature of the outside water.

Two separate circuits

The temperature exchanger is by far the most common system. The coolant circulates around a bundle of tubes contained in a metal housing. In this bundle, also called honeycomb in this case, seawater is circulated to lower the temperature of the cooling liquid. The heat exchange takes place through tubes made of copper, which is an excellent thermal conductor. The heat exchanger box is usually placed on top of the engine and bolted to the exhaust manifold. When such a system is added to a land-based engine, it is called a marinization .

This heat exchanger must be maintained.

The thermostat, a permanent regulation

To prevent the temperature of the engine from being affected by the temperature of the outside water, or by its operating speed, which makes the pump turn faster, a thermostat (or calorstat) is inserted in the circuit. This is a small piece of metal that expands when heated: when cold, it is closed. As soon as the engine reaches the desired temperature (usually 82°), the thermostat opens to let the coolant through. This device allows the engine to quickly reach its ideal operating temperature, regardless of the outside temperature conditions.

Recycle calories

Dissipating heat is one thing, but it can also be useful for heating or hot water production. Rather than releasing the heated water back into the natural environment, most builders first circulate it through the coil of a hot water tank. This insulated tank contains water that heats up when it comes into contact with the cooling water. This is an efficient and ecological way to produce hot water on board, using calories that would otherwise have been lost.

Beware of frost!

The heat exchanger system has 2 circuits. The principle is relatively simple and easy to understand for those who take the trouble to look at their engine and follow the path of the pipes that extend it. The basic precaution is to make sure at each start-up that water is flowing to the exhaust.

If the flow becomes less powerful, you should think about checking the water pump or even cleaning the exchanger cluster. It is important, especially as winter approaches, to check the level and quality of the fluid in the internal circuit. It must contain a four-season fluid that is not likely to freeze. The same applies to the external circuit if you are sailing in fresh water.

Monitor the turbine

The water from the external circuit is sucked in through a valve attached to a through-hull. The pump is driven by the motor. The rubber blades of its turbine wear out with time, alluvium and especially when it happens to run dry during start-ups. The water then flows through the honeycomb. This can become clogged over time and is something to check if the cooling becomes less efficient. The water is then discharged into the sea, usually with the exhaust gases.

The cooling system is one of the most important components of a marine engine, but there is no unfathomable mystery to it, and its maintenance is within the reach of an amateur, whether it be replace the pump impeller or clean the exchanger bundle .

/

/