You are in the middle of sailing, peacefully at the helm of your boat, when the VHF spits out a message that wakes you up from the torpor of the ocean. An authority - a CROSS - calls you. The first call is not enough to make you react, you have to admit that your ear is not permanently on the VHF. On the second call, there is no doubt that the boat the operator is calling is indeed you.

Surprised, you grab the microphone and answer the message. Clear channel, you clearly feel that something important is going to happen without knowing exactly what it is.

The operator doesn't mess around. In the area where you are, a person has fallen overboard and the crew has lost sight of him. He asks you, in fact orders you, to take part in the rescue operation. He purposely gives you a GPS point to reach and asks you for an ETA (estimated time of arrival) and to contact him when you are close.

Start of the research

The search operation in which you are going to take part starts at this moment; and you are responsible for watching what you see on the water. The CROSS operator does not leave you without instructions, however. He explains the other means involved (aircraft, other pleasure craft, SNSM ...) and provides, as you go along, the essential information:

- Color of the clothes

- Body type

- Place of fall

- Place of last vision

Which allow you to refine your search.

All the crew must be active

From the moment you take part in this operation, you and your crew are under the authority of the CROSS (you become a means) and must at least maintain a visual watch of the vessel's surroundings.

Each crew member wears a life jacket so as not to aggravate the situation in case of a fall. Because by looking away, he might not foresee the boat's movements, the lifeline is at the post and attached to the vest's harness. No one smokes (to avoid eye irritation) and everyone wears sunglasses to avoid being dazzled.

Do not use binoculars (they reduce the viewing area too much) and, before you start, clean the cockpit windows. Cleaned windows will not only allow you to see better, but will also prevent the eye from constantly having to refocus (adapting to the distance, adapting to the track, adapting to the distance ...).

At night, turn off all lights (except regulation lights) to avoid reducing visual sensitivity. Depending on the person, it may be necessary to wait half an hour at night for the eyes to become accustomed to low light.

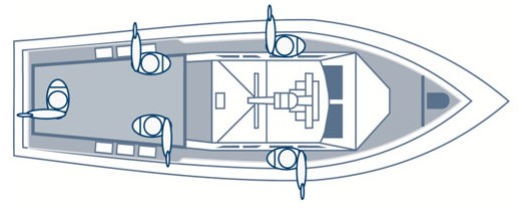

You arrange your crew so that all 360 degrees around the boat are covered. You, as the skipper, will manage the front area of the boat. One crew member will be placed at the stern and one on each side. This is the optimal situation, the more crew members you have, the narrower the observation area.

Finally, every 30 minutes, rotate the crew. With two crew members, reverse the sides (the port crew member goes to starboard and vice versa). With three crew members, each will turn 90 degrees to the left. Ideally, if feasible, keep a spare crew member. Stress, nervousness and the rush to do well are factors that will increase fatigue. As a leader, as soon as you see one of the observers rubbing their eyes repeatedly, it's time to take a break, as each rubbing will mechanically alter the shape of the eye that has adapted to the environment and require readjustment, which again may take half an hour.

Divide up the observation area

The principle is elementary, divide the surrounding 360 degrees by the number of team members. Each one must therefore scan an angle of X degrees in front of him.

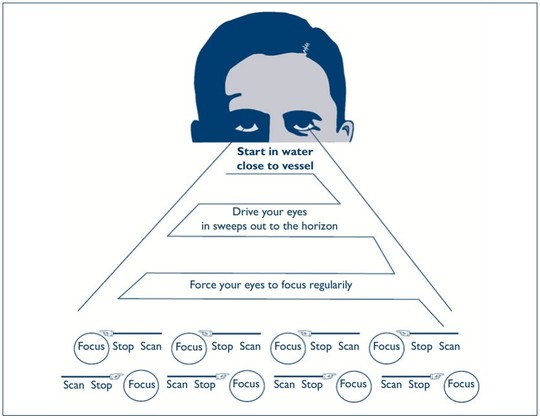

This is the area, and the only one, that your team members will scan by default. This scanning starts at the observer's feet and gradually moves away, in parallel lines. The eyes (the gaze) remain fixed, straight ahead. It is the neck and back muscles that are much stronger and more solid, and which execute the movement of the head to scan the observation zone.

It is in a cycle that the observation is made:

- Moving the head to the area

- Stop

- Adaptation of the vision

- Observation

- Moving the head to the area

- Stop

- Adaptation of the vision

- Observation

And this, on a maximum angle of 15°, beyond which the observer will get tired faster.

You start the observation as close as possible to the boat (at the first point where you can see the water) and move to the right in a maximum angle of 15 degrees.

You stop the movement, give your eyes time to adjust and take stock.

You look at it thinking " i am seeing this or that ". If it helps, say it out loud, hearing yourself say something can cause a more effective response.

Repeat the movement of the head, always to the right.

When you have reached one side of your viewing area, move your head, by the neck, up a few degrees.

This new position will be the first point of observation. Again, give your eyes time to adjust and take stock, then look.

When you have covered the entire area from the nearest boat to the horizon, give yourself a break. Why not take 30 seconds for example to look at nothing actively to give your eyes a little rest.

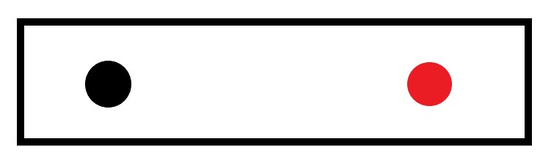

Beware of the blind spot

As it functions, the eye has a blind spot, which is called the Mariotte spot. This is the area at the bottom where the optic nerve connects to the sensitive rods. This area sees nothing, it is the brain that cheats and recreates the vision. In other words, what we see in this area does not actually exist. Or worse, it exists, but we don't see it. And if it is a castaway, this may mean that it will be invisible. For this reason, the gaze must be slightly diverted from the central axis of mechanical vision to be sure of accurately capturing what is seen.

To convince yourself of this blind spot and to reveal the location of your own, do this exercise:

Cover your left eye of the hand and set the black dot. Approach your face from the screen slowly. At some point, the red dot disappears from your field of vision!

Use the way of looking

At night, the rods that line the back of the eye become less and less sensitive the closer you get to the Mariotte spot. It is therefore all the more important to remember to use peripheral vision and to be prepared to see light from the sides.

What exactly are we looking for?

Search, yes, but search for what? Assume that it is nothing more than a tiny orange dot (the castaway's life jacket) in the foam. In other words, a needle in a haystack. And this haystack is always moving.

This needle can take many forms. The glow of a fire, smoke, something moving, a coloring of the water, a parachute coming down from the sky, a firework... Anything that is not common on the water can be considered as the castaway. And to every doubt, the same procedure:

- Keep your eye on the thing you see

- Reach out to the thing

- Have another team member use the binoculars and look in the direction indicated by the finger

- Remove the doubt.

If it was something else than the castaway, you continue the observation forgetting what you just saw ( the brain loves artifacts ) and continuing the scanning cycles in the same order as before.

The victim found, do not lose sight of him

Luckily, you are able to locate the victim. This is the moment when things must be done calmly and methodically. You keep your eyes fixed on what you have just seen and reach out in his direction.

You have the doubts removed and, if positive, the binocular crew member must say what he sees with clarity and in words that are understandable:

" I see a person with a vest. She's making arm gestures. It's a man with glasses."

Or again

"I see an orange life raft."

In short, he has to say what he sees so that the whole crew is aware of this fact.

The two team members who have seen then take turns to maintain visual contact with the victim at all times. If the time is long and they tire, they can be replaced by another who will have to see and describe what he sees before replacing. If the description differs too much from what was initially seen, it is plausible that he thinks he sees, but does not. He cannot, therefore, be considered reliable for maintaining eye contact.

To warn that one has seen does not mean to move

The captain immediately contacts the authorities and explains what was seen and in what direction. Again, the clearer the details, the better the decisions made by the operator.

This operator, moreover, will at this precise moment transmit clear instructions that you must scrupulously respect. These may include, for example:

- Rendezvous with the castaway

- Launch a rocket to make your area visible from the sky

- Set off a smoke bomb

- Maintain eye contact only

You may indeed be surprised that you don't have to make contact immediately. This is logical, as you may not be the only boat involved. In this engaged armada, the operator will have established several functions, depending on the manpower at his disposal:

- Observers ( his eyes )

- Recoverers ( his hands )

- Rescuers ( its doctors )

- Airborne resources ( his feet )

- Divers ( its specialists )

- ?

And you don't know exactly what your mission is. By going to the area without instructions, you could endanger other actors of this rescue operation that you don't know about, a diver for example.