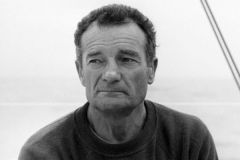

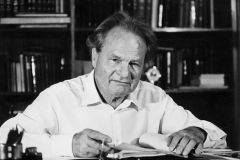

Gérard Petipas is an old hand at ocean racing. He knows the stories and anecdotes of just about every race held in both hemispheres over the last 50 years. But he's not just a passive historian of ocean racing. As a sailor, he personally took part in many of them. Not least the famous Sydney Hobart, a race not as simple as it seems.

A hard, organic, living sea.

" No race is ever simple or easy "This is what Gérard Petipas tells us about the southern classic ".. But the Sydney Hobart is a complicated race. It's a long race, requiring constant and sustained attention. In 1967, we experienced unfavorable weather as we entered Bass Strait. "On the subject of the South Seas, the navigator adds: " The sea is hard and heavy. It's alive. When they hit the bow of the boat, the waves are aggressive and nasty. It's an organic sea. "The changeable weather contributes to this feeling. " When we left Sydney, we were in the middle of summer, wearing short sleeves and shorts. Barely two days later, we're in the middle of winter, wearing parkas and oilskins. There's no transition like you'd see on a classic North-South race. "

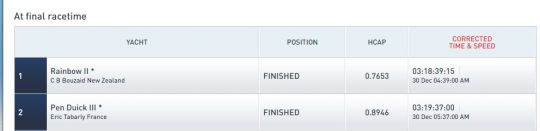

Rating error in the ranking

In fact, the race rankings have been turned upside down, as the navigator explains We wanted to finish first in real time. The corrected time worked, and we came second. Except that, a few months later, Éric [Editor's note: Tabarly] realized that the rating applied to Rainbow II was incorrect. Although the official ranking remained the same, we actually won the race on both the real time and compensated time tables. "The young crew won the race in 4 days and 4 hours.

Invited to take part in the race by Australia

It was the often surprising conditions that prompted the skipper to take his Pen Duick III on board for the race. His navigator tells us: " We had raced the entire RORC season, in England, Sweden and France. Eric accepted an invitation from the Australians. A team from the Admiral's Cup invited us to come and race the Sydney Hobart. It's one of the world's 3 famous races, along with the Fastnet and Bermuda. Of course, we were tempted to go and race it. "Only, material conditions being what they were then, things weren't going to be as simple as they seemed: "We had to come up with solutions. First, to move the boat. Then to move the crew. Only two of the crew had a job: I was a merchant navy officer and Éric, a French navy officer. All the others were either students or conscripts with no income. Éric found a solution: he made an agreement with the Compagnie des Messageries Maritimes to transport the boat to Sydney. For the crew, thanks to Mr. Messmer, who was Minister of the Armed Forces, and because Éric was still in active service, we were able to benefit from seats on flights reserved for military personnel aboard planes going to Nouméa. We were thus able to take advantage of extremely reduced fares to get to New Caledonia. "

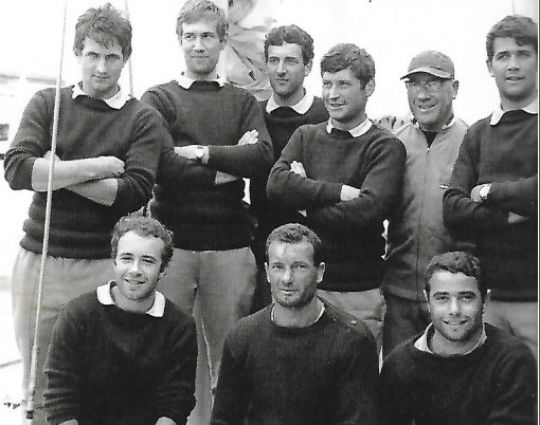

An overstocked crew

The schooner's young, motley crew is outnumbered, as the sailor explains. " The summer crew consisted of Monsieur Tabarly Père and Patrick, Éric's brother. Olivier de Kersauson and Michel Vanek were two conscripts on board. It was one of Éric's agreements with the army to embark conscripts for their training. Pierre English, Philippe Lavat, Yves Guégant, Éric Tabarly and myself [Editor's note: Gérard Petipas] completed the sailors' complement. We were joined by Jean Pierre Biot and Claude Durieux, both journalists with Paris Match. "

Winning with elegance

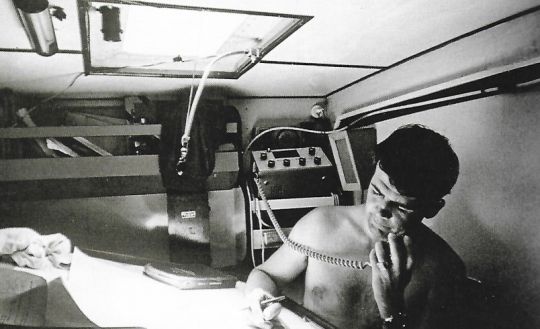

The feeling of winning a race is always exhilarating, whatever the sea you're racing in. Victory is all the more motivating when it's part of a series, as Gérard tells us: " We had already won 6 races, and the crew was highly motivated and close-knit. It wasn't long before, when the positions were transmitted by SSB, we realized that we were leading the race. "A race that ends with a bang. " We little Frenchmen, used to sneaky finishes, win a race in Hobart in front of thousands of spectators on the other side of the world. We were at home with the Australians, and we won. Australia, New Zealand and Tasmania are all lands of sailors. Even back then, they had a real sense of what it meant to win a race. These people have the crew's conscience. "As French tradition dictates, our national crew couldn't be satisfied with just winning first prize, they also had to win another trophy. " We also won the elegance prize. Before we set off, I went to meet Bernard Lacoste, who provided us with free shorts, polo shirts and all the outfits we were going to wear. We looked great, and it showed! "

The sea remains the same, whatever the era

Does the navigator see any essential differences between the 1967 race and the one that will start this year? " Boats have made spectacular progress. Like everything else, sailing is an eternal restart. After the multihulls had finished killing off the monohulls, Éric said, "One day, the architects will get interested in monohulls again, and there will be a quantum leap in the performance of these boats". History has proved him right: the monohulls used in such races are phenomenal, both in terms of size and design. But let's not overlook one thing that remains the same. The sea is as unforgiving and demanding as ever. It was the same 50, 100, 200 or 1000 years ago. When the navigators of antiquity took to the sea, they faced similar navigational difficulties to us in 1967 or to the racers of 2020. "

Managing to finance the boat

It was their ability to manage on their own that enabled this fine crew to take part in and finance the race, as Tabarly's friend explains We all had a duty to find solutions and tricks. A grocer would offer us pâté, a baker bread or a wine merchant wine. We managed to have a complete kitchen at reduced cost. This was the key to having a boat in the best possible condition. Everything that came in was injected into the boat. Renault gave us a diesel engine, and a rigging company gave us all the ropes ". Looking for financing, a full-time job then as now. He concludes " Look at Jean le Cam on the 2020 Vendée Globe. He's a brilliant sailor, but he had a hard time financing Yes we Cam! "There is no correlation between the qualities of the sailor and the financing he will receive.

How do you prepare for your race?

" Advice can't be given. "Gérard explains when asked what he would teach a beginner today. " It's up to you to prepare your navigation in your own way. Don't throw yourself at technology and modernism. They help, but they don't do everything. Remember that the sailor is still the one who works on board. He's the one who gets the job done. These days, there's no such thing as an unassisted race. In the event of damage, all you have to do is pick up your iridium to get assistance from the boat. It's neither good nor bad, but you also have to think about what you can do without it. "

A kind of mystical experience

On the subject of communication, the friend of the silent Éric Tabarly explains: " Talking too much spoils the adventure. There's something mystical about ocean racing. For most sailors, setting sail is a spiritual retreat. Some sailors don't want any means of communication. Others go there to retreat. That's the case with Parlier and Poupon. At the other end of the spectrum, others are extremely gifted at communicating. Take Loïc Peyron, for example. He's more than a communicator, he's an explainer. He'd certainly be just as good at talking about Formula 1 as he is about ocean racing; he knows how to teach things and make them understandable to as many people as possible. "

Chance and coincidence are the spice of life

One of the anecdotes from Gérard's fascinating life is linked to Éric Tabarly's marine mutism. " At the finish of the '67 Sydney Hobart, Philippe Gildas asked me to accompany Eric to Hobart for an interview. As usual, Éric wasn't very talkative, so I answered the questions and conducted the interview. That's how I got my foot in the door of the airwaves. Gildas spotted a talent for radio in me, so I joined RTL, where I worked for 5 years, then Europe 1, for around 15 years... "

/

/