Dominique continues her account of her cruise to Antarctica. But the adventure changes after the boat violently hits a rock ( read episode 7 ). An ingress of water invades the tank of diesel polluting the fuel. What can be done? Dominique tells us how difficult it was to decide what to do next, after gaining an anchorage stuck between the land and an iceberg.

An unglamorous technical assessment

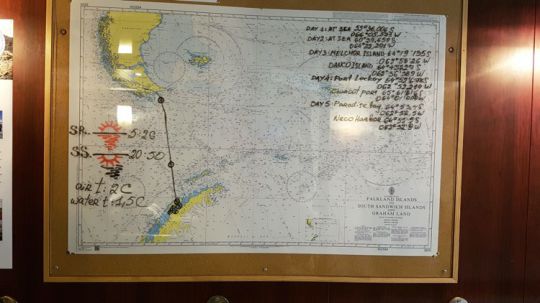

On board the atmosphere is very tense and gloomy. We have 140 litres of uncontaminated diesel left in cans, which is 24 hours of engine power or 150 miles at best. That's not enough to reach the Argentinean base of Deception, which remains open all year round. It's February 22nd 2019 and that's the end of the season. The summer bases like Videla or Lockroy are closed or about to close. Most of the ships in the area will cross the Drake again in the coming days. We have a large hole in the keel, as evidenced by the flow of seawater through the tank vent and the engine return circuit. At the moment these two inlets are being dammed by a pinoche and a potato. The impact was very violent and we have no idea of the structural damage caused. The Drake, known for its gale force winds and rough seas, is certainly the last place in the world where we should have to worry about this kind of thing!

A round table discussion of the crew

Once the mooring manoeuvres are completed, the captain calls the crew together. Each person must give his or her opinion on the situation and specify the decisions that seem appropriate. It is the captain's privilege to be the first to express himself: " I'm asking you not to say anything about what just happened, because I'm not insured in that part of the world.. "? " Regardless of the state of the boat, I'm going back across the Drake with the first weather window that comes along. "At least it's very clear. In order: Sara, Carole, our crewman, myself and the captain's wife. Sara, Carole and the crewman are unanimous, without any prior consultation. First of all, they want us to immediately inform the fleet in the zone of our situation: on the one hand to point out our precarious situation, and on the other hand to try to obtain additional fuel enabling us to reach one of the bases in the surrounding area that are still open. They all specify, in turn, that they will not cross the Drake again with the boat unless a precise diagnosis of the damage caused is established. On the other hand, the captain's wife, the last to speak, sided behind her husband.

No agreement to proceed under these conditions

For my part, this latest accident has taken away my patience: I no longer have any confidence in either the boat or the captain. On a technical level, I can't stop thinking that for one problem identified on board, there are at least ten ("the law of icebergs") that I haven't spotted. What other critical part or equipment is going to fail due to lack of maintenance or simple negligence? I don't see myself facing a big dog hit in the Drake aboard this boat in this condition. I, in turn, can sum up my thoughts in a few words: " That ship shouldn't be in this part of the world. If I'd known her condition before I left, we never would have taken Carol and me on board." .

Captain's decisions questioned

However, while I've had serious doubts about the general condition of the boat for quite some time now, the captain's last words have made me even more dismayed. Whether or not the boat is insured, at this stage, is of little importance. No insurance would get us out of this faux pas. At sea, we are all at the mercy of an accident or a navigational error. And what makes the difference is the captain's ability to make the right decisions and to unite his crew to manage the crisis, especially in such hostile areas as the Antarctic where you can only rely on yourself.

And there, the captain's decisions seem to me to be totally inconsistent; even worse: dangerous. To begin with, putting on the brakes to warn the fleet in the zone of our precarious situation. It should be noted that south of 60 degrees, there is no longer any assistance service at sea and that we can only rely on mutual aid between the various ships and boats in the vicinity.

And even worse, to want to get into the Drake:

- without a diagnosis of the damage done.

- with potentially large water inlets temporarily clogged by a pinoche and a potato.

- with a fuel reserve that will not even be sufficient to recharge the batteries on board for the duration of the return trip, let alone allow the boat to progress if it encounters an area of calm or headwinds.

For me, it's sheer madness.

A stubbornness difficult to understand

What revolts me is that, for a story of insurance, the ramifications of which only he understands, the captain is willing to risk the lives of his crew.

Whether the captain and his wife put their only lives in danger, why not, they are old enough to decide for themselves. But for the captain to play so lightly with other people's lives seems totally unacceptable to me.

Besides, I have the unpleasant feeling that I've been cheated. I leave it to the "mathletes" to calculate what "6 team members x 80 euros/d x 60 days" does. Excluding the "board box" (the contribution to the costs covering food/drinking/diesel, generally set at 25 to 30 euros per day and per person in the "deep south"), there was certainly a sum left over that could have been used to maintain and prepare the boat and the safety equipment

An "alert" with just two short emails

The majority of the crew therefore voted in favour of immediately notifying the fleet in the area and the captain reluctantly agreed to agree with the majority. However, his intervention is limited to sending two emails to friendly sailing boats which should still be within a radius of a hundred miles. His messages in no way reflect the seriousness of the situation. He merely states that " our diesel is contaminated by sea water for unknown reasons "and to solicit" some diesel and a RACOR filter ". Not a word to the maritime authorities present in the surrounding bases (Chilean Armada, Argentinean Armada, American Navy...) who, for their part, would be able to relay our situation to all the boats in the vicinity, and especially to the biggest ones with the reserves of diesel to help us out.

Only the captain and his wife want to stay on board..

The night is long, almost white for most of us, because everyone knows that they are faced with an exceptional situation, which can be fraught with consequences depending on the decisions taken. If the sleeping configuration is ready for the side-by-side - the 4 crew members sleeping in the bunks in the central saloon, the captain and his wife in the aft cabin - nobody talks during this long night, nobody shares their doubts and worries, not even Carole and I between us. The next morning, the situation is even more tense on board. After breakfast, we go around the table again and everyone gives their position after the night of reflection. In order: the captain and his wife, who want to bring the boat back at all costs at the next weather window at the beginning of the following week. Then the crew member who declares having lost confidence in the boat and believes that the Drake's return in these conditions is too risky, joins Sara and us in asking to be evacuated. Incidentally, a crew member takes a look at the distress beacon on board: it has been expired for 4 years... What about the life raft? Distress flares? When confidence is lost, imagination takes over.

An atmosphere of mutiny

As the tone rises, and I inform the captain that I'm going to take it upon myself to contact the outside authorities if he doesn't do so immediately, a large RIB expeditionary vehicle passes at full speed in front of the bow, with a dozen tourists on board. They respond to our great gestures of distress with great greetings and strafe the boat with their telephoto lenses. The surprise is as unexpected as it is brief: they are already out of sight. It is true that in our ice enclave, our visibility is less than 50 m. Several VHF Pan-Pans remain unanswered (the ice cliffs reduce to nothing the already failing range of the VHF). And then suddenly, a second RIB loaded with tourists appears. This time, the whole crew is on deck and goes on a rampage to attract the attention of the boat unequivocally!

All crewmembers request to be disembarked

The RIB is approaching and we quickly explain our situation to the polar guide, Stefano, who is at the helm. He tells us that he will refer to it on board after dropping off his passengers. He quickly returns with Oleskey, the ship's mate, accompanied by the chief engineer and Sam, the expedition leader, a young and friendly Quebecer who is in charge of 200 tourists, mostly Australian, aboard the Ocean Atlantic. Today is their first stop in Antarctica, after leaving Ushuaia 3 days ago, and they are anchored about a mile from our anchorage, on the other side of the ice cliffs. We ask him if the ship can provide us with 500 litres of diesel. We also tell him that the 4 crew members do not want to make the return trip on board and ask to be disembarked.

Assistance to a person in danger

They agree to offer us (free of charge!) 500 litres of clean diesel and to take back the contaminated fuel that has been recovered from the cans. After analyzing the situation, they strongly advise the captain not to enter the Drake until they have made a precise diagnosis of the damage and possible structural damage. They recommend that he head for the Chilean base at King George where he can find divers equipped with equipment, or even a crane to take the boat out. Once again, the captain persists: whatever the diagnosis, he will pull the boat up through the Drake. Given the seriousness of the damage and the risks incurred in the Drake, and in view of the captain's determination, the captain of the Ocean Atlantic, instructed by his chief mate on the situation, considers our request to disembark to be legitimate and records in his logbook the taking on board of 4 people.

Change of position for one of the crew members

As he boarded the RIB, the fourth crew member, an old friend of the captain and his wife, changed his mind at the last minute and decided to stay on board.

For our part, Sara, Carole and I are boarding the Ocean Atlantic which will take us back - free of charge - to Ushuaia. But not before we've done the whole peninsula trip we've just completed in 5 weeks... The welcome on board, the kindness and generosity of the whole crew and the hotel staff are exceptional. That is how we will make 2 cruises in Antarctica during this same trip: one on a sailboat, the other on a comfortable "liner".

News from the ship

We will no longer have direct news from the yacht, despite attempts to contact us by email. A message from the captain of the Ocean Atlantic will be received a few days later. After our departure, the latter would have established contact with the Belgian boat we had met earlier, equipped with diving equipment and able to assess the damage to the hull. Apparently, they were able to fill the breach in the keel with epoxy putty and the boat would then have left for the crossing of the Drake.

Fortunately for the crew, the boat finally arrived safely in Ushuaia about ten days later.

Antarctic Adventure increasingly popular

In the age of social networks, it seems that there are more and more candidates willing to take inconsiderate risks in order to live the "Adventure", whether it be climbing Everest or going down to Antarctica on a small boat. Even with all the technology available today (in terms of weather forecasting for example), the risks still exist and haven't really changed since Shackleton or Charcot. The tragic accident of the boat PARADISE last year between South Georgia and Uruguay (2 missing, the captain and a crew member, both extremely experienced and used to the Antarctic Ocean) sadly illustrates the perils of this part of the world.

In the wake of the explosion of tourism in Antarctica on cruise liners and some large professional sailing ships, a parallel charter - very lucrative - on small sailing ships has developed.

An expedition, but not an adventure

In conclusion, I would like to quote Amundsen's words when he was preparing to conquer the South Pole: "There is no room for adventure in an expedition. If there is adventure, it's because we were insufficiently prepared". For us, this trip to Antarctica was a real adventure: an exceptional experience, where we were able to closely observe the enchantment of nature and feel the absolute serenity of these places, but with a level of risk far greater than we have ever tolerated when sailing around the world with a small crew on our own boat.

If Antarctica tempts you, keep in mind that Antarctica under sail remains a real expedition.

Avoid our mistakes

My advice: don't do what we did! Don't commit yourself to joining a crew based solely on the jovial and friendly nature of the skipper. These are not the primary qualities expected of a good expedition leader. While it is impossible to prejudge the skills, reliability and resilience of a captain outside the heat of the action (at the bar, we are all "MacWhirr Captains"), it is important to remember that we are all "MacWhirr Captains" - Typhoon, by Joseph Conrad ), it is, on the other hand, fairly easy to estimate the state of maintenance and preparation of a boat by inspecting in detail its important nerve centres: the engine; the autopilot; the steering sector; the rigging; and the sails. And to draw the consequences on the preparation of the captain himself. A boat, even an old one, must be beyond reproach for such an expedition.

Check inventory

The stock of spare parts on board is also critical and it is important to know the inventory before leaving: alternator; starter; pilot cylinder; booster pump/injector/injection pump; spare shrouds... Without forgetting the stock of consumables sine qua non: several diesel filters (primary and secondary) and spare oil filters; large quantities of engine oil and transmission oil... This will in no way prevent breakdowns or even accidents. They are the daily lot of long-distance sailors. But if the boat is well maintained and prepared, the probability of an unexpected breakdown is reduced and, above all, you can deal with it when the time comes, because you are equipped and prepared for it.

Giving our full confidence to the captain, we had not, before departure, inspected the boat as we should have done, nor had we taken stock of the inventory of spare parts and safety equipment. And that was a big mistake. A mistake that could have had serious consequences.

Reassuring professionals

And finally, if you feel you do not have the technical skills necessary to assess the condition of the boat and its preparation, or if you cannot remotely obtain sufficient guarantees that the boat you are looking for is really ready for such an expedition, it is better to rely on one of the reputable professional tall ships. This will certainly cost you a little more, but at least you can be sure that a good part of your contribution will have been spent on the maintenance and preparation of the boat, the professional qualifications of its crew and its safety equipment.

For a trip to Antarctica - for many of us the dream of a sailor's life - the "almost-about" is not a must and we will never regret having made this expedition in optimal and safe conditions, even if the latter will always reserve their share of the unexpected and the adrenaline rush that goes with it.

We've contacted another crew member who will explain his vision of things. To be continued...]