Still heading south to Antarctica, Dominique continues her story and shares her logbook in this episode 5, a tale of discovery of the ice and the wildlife that survives in these regions.

Heading for the British base at Lockroy. The weather is very foggy and very cold. Visibility is very poor. It rains and snows all day long; all our outfits are soaked. We cross an area of solid ice, thin enough for the bow to pierce it again, but thinking back to the misadventures of Shackleton caught by the ice in this part of the world (in the Wedell Sea) a little more than a century ago, we are delighted to get out of it!

The Lockroy base is the most visited of all the bases on the Antarctic Peninsula. Contrary to the other bases, the Lockroy base has only a strictly commercial vocation. During the 3 summer months, Lockroy welcomes 18000 tourists and its souvenir shop, doubled by an office of the "Her Majesty Royal Mail", established in the original premises of the scientific station does not deplete.

We will have to wait 2 days to be able to visit the Lockroy base which has a maximum quota of 350 visitors per day. The cruise ships that follow each other daily book their visits to the base from one year to the next, and we have to wait for a gap in the schedule. There is a lot of wind in the anchorage where we are, but we are holding on to our 4 moorings hit ashore (even if a sea leopard gets the urge to bite one).

The engine of the dinghy that's giving up the ghost

The vessel is equipped with only one small tender limiting us to a maximum of 4 adults to navigate safely. It is equipped with a heavy 9.9 hp petrol outboard. To get to the base half a mile away and disembark, the outboard motor is essential to make several round trips. But this one, which had already given us a few worries at Whaler Bay with idle-holding problems, is giving up for good. He didn't want to restart despite multiple frantic attempts. Fortunately, we were close enough to the edge to finish rowing, as with the strong wind blowing from land, we could have been dragged out to sea.

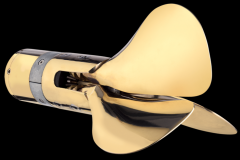

The speedboat will not be repaired by the end of our expedition, forcing us to fall back on a small electric speedboat. At this stage, all that's left to move around is a Torqeedo with 1.5hp and a range (in perfectly calm weather and on a reduced charge) of 30 minutes for a 3-hour recharge.

For my part, I consider that this type of engine has no place on a boat sailing in the Deep South. Its plastic propeller can break on the first contact with an ice cube, and its low range and low power are perfectly unsuited to the brutal wind and swell conditions that can suddenly appear and require you to put "the rubber" to get back on board, especially with the dinghy loaded.

The generosity of the crews in the area

The cruise ship Le Lirial anchors in front of Lockroy and disembarks its passengers. The expedition leaders, intrigued by this small sailboat solidly anchored to the coast in its rocky crevice, visit us between 2 rotations and bring us fresh bread and croissants.

Gas shortage..

This is very fortunate, as we have just realized that one of the 3 gas bottles planned for this expedition has not been loaded correctly. We still have 1 month to go, and we only have one gas bottle left. At 6 people, baking bread every day, it's too short. In reserve, we have a small camping stove and a dozen gas cartridges. If we are very careful, and especially use the pressure cooker for all the food requiring a long cooking time, we should be able to get by.

Just next to Lockroy is the Dorian Cove anchorage, one of the most beautiful anchorages we will encounter in Antarctica. The sunset lights shining on the ice sheet are exceptional, hypnotic.

Ashore, there is still an Argentinean hut that can be visited, guarded by a few penguins not at all bewildered by our presence.

High voltage navigation in ice

We are waiting for the "all clear" to try to cross the Lemaire canal which is closed by ice. The Lemaire is one of the most spectacular passages in the area, but the cruise ships we contacted confirm that it is at this stage impassable for them. However, the captain decides to try. The helmsman has to concentrate on the sole instructions of the lookout stationed on top of the hood to weave between brash, floes, shelves, growlers and other forms of drift ice (there are 27 different names, depending on the size and configuration of the ice) to minimize impacts on the hull. Even so, the impacts are sometimes muffled and shake the whole boat right down to the rigging. A fibreglass hull would be really put to the test in such an environment.

In the footsteps of Charcot

At the exit of the Lemaire, we come out onto the Salpêtrière, a graveyard of large icebergs that have come to ground there under the combined pressure of the wind and the tide. Charcot, who had wintered next door in 1904, named this place in honour of his father, then director of the Parisian hospital of the same name. Under a blue sky as perfect as it is intense, in the softness of the sun and on a sea of oil, we spend the afternoon wandering between these gigantic masses of motionless ice, in the midst of numerous whales busy with their krill feast.

We eventually find the narrow passage leading to the Pléneau anchorage, where once the boat is well secured on her 4 moorings ashore, we are in perfect safety, as the biggest icebergs run aground on the shoals closing the pass. And that's a good thing, as the next day a standing wind rises and huge ice masses, which would crush us in the blink of an eye, are heading towards us, only to come to a sudden stop just a few cables from the anchorage.

To be continued...