Taking part in the Fastnet means tackling one of the most demanding courses in ocean racing. For an amateur crew and a 50-year-old Nicholson 33, the adventure takes on a special dimension. Delayed delivery, strategic errors, damage at sea and the joy of finally reaching the mythical lighthouse: this is the story of a determined crew, where perseverance counts for more than the rankings.

Waiting before departure

What a thrill to witness Cherbourg's extraordinary welcome organization: the ballet of racing machines arriving at the quayside, the feeling of being small and out of step with the competitors' yachts, but above all, the pride of taking part in this regatta. These were the hours I spent waiting for my crew, delayed a day by an undelivered parcel, then again by a car breakdown on the road between Vannes and Cherbourg.

We'll be the last boat, excluding Ultimates and IMOCAs, to leave Cherbourg, but at least we'll have been able to get a spot on the regional France 3 news channel.

A night with the big names in sailing

We sailed until dawn, arriving in the Solent only to be overtaken by faster boats that had left at the end of the night. It was an emotional moment to be sailing alongside Sidney Gavignet, whom I had met years ago at the Cape Town Yacht Club, when I was sailing ANNKA, a Garcia 62 taken from Turkey to Brazil, and he was taking part in the Volvo Race. What a night we had!

And this boat, the Cigare Rouge of one of my emblematic sailors VDH, who awarded us the Prix d'Elegance at the Bois de la Chaise regatta at the dawn of the 2000s with my father's Chassiron GT. Also among the fascinating Class40s or Petits Princes, Elodie Bonafous' IMOCA... The race hadn't even begun, but the memories were already piling up.

The difficulties of the Solent

The lack of preparation and the hasty departure for Cowes prevented the crew from finding the right synergy to get into race mode. No matter, we're part of the fleet, and I'm now living up to the goal I've been building for several months: to take my Nicholson 33 to the Fastnet, for her 50th birthday and the 100th anniversary of the race just one year after acquiring her.

We're racing in the IRC4 class, among the regulars. I admire the fluidity of the maneuvers of the seasoned crews, and envy the precision of their actions. Obviously, on Seabird it's not so fluid. The Solent keeps its promise: running against the wind.

With the help of common sense and observation, we held a good position in the fleet, until the threatening cloud burst with the squall it heralded. The wind and current shear is too strong for this small sailboat, which becomes unmaneuverable. Just enough time to adapt the sails and get back on course, to understand this suddenly hazardous behavior, and we're swept away by the overturn. The sea becomes short, high and violent, like a minefield.

Ireland in the fog

At last we pass the Needles, this exit from the Solent is a liberation. But as usual in July, we're sailing headwind, just in line with our route to the Fastnet. We opted for a southerly breeze, hoping for a stronger wind and a better course. But successive helmsmen see things differently. I discover at the end of a deep rest to make up for the very short overnight delivery, that we're sailing close-hauled perpendicular to the coast.

I take it upon myself not to tarnish the fragile atmosphere. We worked our way upwind as best we could until we reached the Scilly islands, where I in turn made the stupid decision to pass to the south of the traffic separation zone. The uncertainty of a committed wind rotation that I feared would force us to tack endlessly against the current, the absence of an up-to-date weather file, nerves already shattered by the violent pounding of the hull with each wave taken head-on, disappointment at the lack of fluidity in exchanges on board, the confusion of thinking that the road was still a long one. In short, this bad strategy will make us extras in the rankings, and I'll be brooding silently over my profound annoyance.

Damage and perseverance

What remains is the joy of being at sea, the absurd delight of total discomfort, soaked, salty, exhausted, jostled at every turn, head-on in a rough sea whose cold spray is a regular reminder of its harshness. To pass the time, we amuse ourselves by listing the pleasures of the land we'd like to savor. Everything from a large dry bed to a duck breast with pommes sarladaises, to a hot bath by the pool in the sun.

But in reality, I wouldn't have swapped the moment for anything in the world, every moment is intense and the hardness that gives so much flavor to comfort also opens the doors of the spirit. We forget our bodies, we ride our thoughts, the wake writes our dreams, urges our considerations on the world, on life as it is, on time past and still passing. Sailing is a path in the mind as much as on the charts.

En route to Fastnet

And so we climbed for three days - felt like ten! - headwinds always between 15 and 30 knots on sometimes heavy seas, to flirt with the Irish coast, tacking square. On several occasions, we were surprised to see much larger competitors appear, whose paths we crossed as we tacked, filling my heart with what remained of the hope of nourishing the pride of not closing the gap... But they're 12, 15 meters long and faster than us. We wanted this lighthouse. And without modern instruments, we would have had it coming.

When we finally approach, a thick, dense mist envelops us in its calm. But there it is, that lighthouse, right there in the bow. A suspended moment. At its feet, a fisherman is at work, and the shift in the myth lends me a smile. This race, this dreaded lighthouse, which seems terrible from my childhood reading, this islet that could be Tintin's Isle Noire, we see it intimate, shrouded in mist, thundered by the pop-pop of a small fishing boat lining its shore.

What remains is a mixture of relief, joy and satisfaction at being there. There's the magic of the sea, of the imagination, of being part of this mythical race.

We swapped the solent (breeze jib) rigged after the Scillys for the large genoa, as we were overtaken by a competitor. On this superb 48-footer, the crew gives us the warmth of their encouragement. The wind picks up as we emerge from the fog bubble, and we hoist the asymmetric large spinnaker.

We're off on a wild cavalcade, exhilarated by the presence of competitors and the fact that we've passed the lighthouse and are on our way home, pushing Seabird to full speed. She's off into endless surges of over 10 knots.

It's hard for him. I know it, I feel it, but this dormant pride negotiates ardently against prudence.

Crac, the spinnaker's in the water...

And as is so often the case... it's paid for in boats. It was Corentin who paid the price. The masthead fitting on which the spinnaker halyard block is attached gave way under the pressure of a slap in the downhaul. The sheet hits the crew member's forearm as it flaps, and the sail is released into the sea. I watch the sequence unfold from the cabin window. At first, I feared that it was the bowsprit, fitted in La Trinité, which had finally ripped everything off under the pressure.

Fortunately for Corentin, the injury is not too serious and is limited to a large hematoma. I help the crew bring the sail aboard from the bow. Fortunately, it's intact. But we no longer have a spinnaker halyard. We hoist back the genoa, and once the arm is healed, I refuse to give in to fate. We lower the sail to hoist the spinnaker on its halyard. And so we reached the Casquets just 2 days after turning the lighthouse. What a ride! It was absolutely fantastic.

Lessons from a crossing

Then there's the classic calms as we reach the Cotentin peninsula: headwinds and currents. It will be a long time before we finally reach Cherbourg after 6 days of racing in total . What a thrill to hear the race committee's congratulations on the radio, with such British phlegm, after a night of complaining about the umpteenth wind shift. We closed the gap, but in the end... since we needed a boat to close the gap, since we were welcomed in the middle of the night by the race director, since we would receive the perseverance prize... And since we did it! Wasn't it better to finish last than anywhere else in the rankings?

Seabird suffered a little, with a few cracks appearing at the chainplate feet and the masthead fitting giving way. The genoa and solent were tired. But I've learned so much from this boat, so much from this adventure that began in December with the sketch of the project.

I just want to keep going! I've contacted the maritime conservatory in Le Havre, where the boat will be wintered, to continue its restoration and preparation for the 2026 season. I now have all the time in the world to solidify the technical, financial and human partnerships I need to continue underpinning my overall maritime project, taking part in races and spreading the culture of a certain type of yachting, based on simplicity and the pleasure of doing things.

Technical advice

A thought for my Steiner Navigator binoculars, which went overboard after 8 years of loyal service. A little practical advice: pay particular attention to wandering vest release cords. The effect is very unpleasant when it gets caught in the reefing line in the middle of a manoeuvre. So don't forget to take spare cartridges with you to rearm the vest.

I'd also like to comment on safety. With no internet on board, we had no way of picking up the weather, no VHF - I was expecting heavier traffic so relay was possible and obviously the freighters called with their IDs didn't answer - and no Blu radio offshore. I didn't want Starlink, but is the choice still possible?

Thanks

I would also like to pay tribute to my partners, NITBY of course, without whom none of this would have been possible, but also MattChem, thanks to whom I have so often received kind comments on the condition of my 50-year-old Nicholson, Milwaukee for the quality of its tools, AD Le Havre for their unconditional support, Le Havre Yacht Service for their advice and guidance, La voilerie Cherbourgeoise for managing our solent so quickly, Axe Sail Cherbourg who had THE furling shackle that allowed us to sail after I noticed it was missing just before departure.

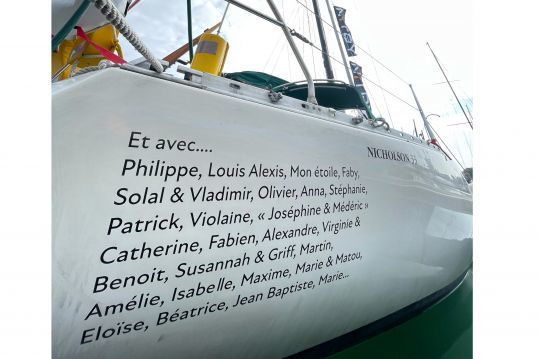

I would also like to extend my warmest thanks to the families and friends who have directly or indirectly contributed to the project through their donations and words of support.

/

/