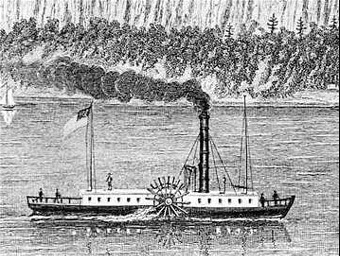

A technical break with the paddlewheel

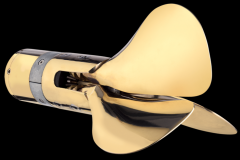

In the early 1830s, when paddlewheel propulsion was used on most European steamships, Frédéric Sauvage came up with a more efficient system, inspired by the scull and fin of fish. As early as January 1832, he demonstrated publicly in Boulogne, using a model weighing less than a kilogram, that his propulsive screw offered superior performance to the paddlewheel. According to the official report on the experiment, the propeller propelled the model three times faster.

Despite a patent filed on May 28, 1832, and several demonstrations in the Paris region on the Ourcq canal and at La Villette, the Ministry of the Navy refused to consider the technology viable for large ships. Experiments carried out in the United States, citing the propeller's inability to pull large units, served to justify the official refusal.

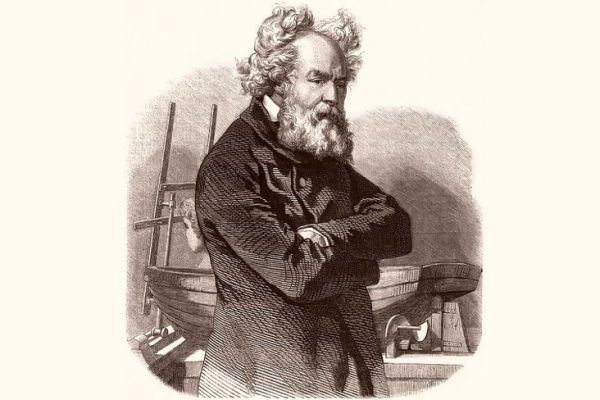

A self-taught visionary out of step with the times

In 1833, Sauvage left Paris and sailed down the Seine on his experimental canoe. In Le Havre, he continued his trials without a steam engine, using mechanical devices powered by human effort to turn the propeller. Lacking funds, he went heavily into debt and sought help from his brother in Abbeville. Attempts to build a boat in Honfleur failed for lack of funding.

Back in Paris, Sauvage briefly exploited another invention, the physionotype, designed to produce reduced busts. But lawsuits and disputes over paternity distracted him from his naval ambitions. Despite extending his patent to aerial applications in 1839, he still failed to convince the technical authorities.

The British Archimedes and the feeling of spoliation

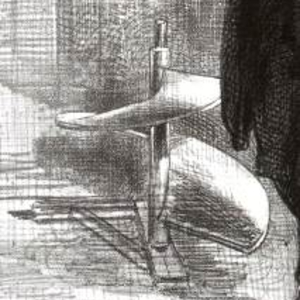

In 1838, a British steamer, the Archimede, was fitted with a stern propeller very similar to Sauvage's concept. Launched in May 1839, the vessel reached 8.5 knots at sea, despite unfavorable conditions. Frédéric Sauvage claimed that his invention had been misappropriated abroad, without recognition or compensation.

The following year, ill and exhausted, he retired to his brother's home in Abbeville. In 1841, a contract was signed with shipbuilder Augustin Normand and English engineer Barnes. They took the risk of designing a 120-hp propeller-driven mail steamer for the French government: the Napoleon. It was a great success, with an average speed of 10 knots. But Sauvage, although owner of the patent, had not participated in the design and could not claim credit for the ship's performance. He protests publicly, but does not call into question the signed contract.

Decay, isolation, madness

In May 1843, Frédéric Sauvage was imprisoned in Le Havre following a judgment by his creditors. He remained in detention for several months, before being released thanks to media coverage of his case by journalist Alphonse Karr. He was awarded a modest pension of 2,000 francs. But it was too late: the inventor was exhausted, ruined, and his mental state was worsening.

In April 1854, he was committed to the Picpus nursing home in Paris, where he died in July 1857, aged 56. His remains were transferred to Boulogne-sur-Mer in 1872, in the eastern cemetery.

The marine propeller: an overlooked technical legacy now in widespread use

Today, the propeller is an absolute standard of marine propulsion, and its principle has hardly changed since the work of Frédéric Sauvage. However, institutional and industrial recognition of this pioneering genius was virtually non-existent during his lifetime.

/

/