Charlie Dalin, born in Le Havre in 1984, is one of the favorites in the IMOCA class. After training in naval architecture in Southampton, he quickly entered the world of ocean racing, notably in the Figaro, before devoting himself to the IMOCA class. In 2020, he made a name for himself by finishing second in the Vendée Globe aboard Apivia after a race marked by exceptional tactical choices and technical mastery. Since then, he has won a number of races, and is about to set off on this 10th edition on his new IMOCA Macif Santé Prévoyance, specifically designed for the solo round-the-world race.

After your victories in the New York Vendée-Les Sables and the Défi Azimut, how would you assess your preparation for the Vendée Globe 2024?

I feel ready for this second world tour. The team has put in a lot of hard work over the last few months. They've spared no effort to get the boat in tip-top shape! I'm really pleased with the state of preparation for this new round-the-world race. I'm really looking forward to testing this boat, designed and engineered for the Vendée Globe. We've been preparing for just over 3 years now. Macif's design began in autumn 2021, with decisions to be made based on this race.

Ergonomics are adapted to long-distance life on the boat, the hull shape has evolved, as has the deck shape... Everything has evolved in the right direction. I can't wait to spend more than 10 days in a row on the boat, to live aboard for the duration of the Vendée Globe.

In your last Vendée Globe, you finished second. What lessons have you learned from that experience for this edition, and what are your ambitions?

I'd like to do better than last time. There aren't many options. Last time, it was a close call. I crossed the finish line first, but with the compensation, I finished 2nd, 2h30 behind the winner.

During all these years of preparation, we've kept in mind that the difference between winning and losing could come down to a few hours. You have to leave nothing to chance and push things to the limit, because it can come down to very little. I'm going to spend a lot of time looking for those minutes.

I've redone the race countless times. It helped me prepare for this one, to look for the smallest minutes, sail changes...

In the last edition, I was quite young in my IMOCA career. For my first Vendée Globe, my racing experience was just 10 days, on the Vendée Arctique. I've learned a lot since the start of the Vendée 2020, I've completed the round-the-world race, I've done the Route du Rhum, the round trips to the United States and lots of other races. I can't wait to test this boat and race it again with the experience I've gained. There are lots of reasons why I'm in the Vendée, but the main reason is to race with experience and apply what I've learned.

The Vendée Globe is a demanding race both in terms of navigation and personal management. What strategies do you use to manage fatigue and maintain a high level of performance throughout the race?

You have to find the right compromise, the right rhythm for yourself. It's hard to perform from start to finish. You also have to find the right rhythm for the boat. It's a race where boats follow and break because wear and tear comes into play. Paradoxically, the moment when you tinker the most is when you enter the Atlantic. The boat has been exposed to salt water for months. Parts are worn out, and more and more. You tinker until the end.

You have to sail at the right pace, and that's even harder to do this year. There are a lot of us, and it's always the other way round. The pace is pretty high right from the start. You have to set up straight away, and everyone is going to start off at a high pace. We've got to stay on the right side of the line and avoid breakage. The boat's parts have a memory and you can feel like you're getting out of a problem, but a few weeks later it breaks because everything is overstressed. It's not the sensors that tell you this, it's the marine sense. Even though boats are becoming more and more technological, your sea sense will tell you whether you're on the right side of the line or not.

You showed great skill in managing weather transitions, particularly during the crossing to New York. How do you anticipate the management of complex weather systems during this edition of the Vendée Globe?

It's true that it's rarely the same thing, even if we spend a lot of time studying the course and the weather, as we do in training with Jean-Yves Bernot. Vendée Globe races are always different, and you have to adapt to new situations. I spend many hours every day in front of the computer at the chart table, studying weather solutions. Every 12 hours we receive a new wind file, and each time we have to start from scratch.

There's also the management of risk-taking, why this or that rider made this choice, the notion of investment to be made... It takes a lot of time. We don't know if the Vendée 2024 will be like the last one, or if we'll go backwards like in 2016. The small group that went ahead was never caught. Every situation can be the last to succeed.

You're alone on the boats, and a maneuver takes a long time. The longest are 45 minutes. When you launch a maneuver that long, you have to do it at the right time. It takes a lot of energy and risk-taking. As the boats are going faster than before, we compensate for the number of miles lost on a manoeuvre by going faster.

I really like this tactical and strategic part. The boat speeds are closer this time than last time. The fleet is denser, so it's sure to be tight at the head of the fleet.

Your boat, designed by Guillaume Verdier, is renowned for its versatility. How does this help you perform in a variety of conditions, and how does it compare with your previous IMOCA Apivia?

Apivia was a very good boat. She had a few weak points, particularly in heavy seas downwind. We've kept the versatility we already had. The good thing about Macif is that it's a boat that continues to be fast even when there's less wind. I can keep up an acceptable speed even if I don't immediately put the canvas back on. When I'm forced to sail out of the wind range, because maneuvering to hoist a sail takes time and energy, the boat glides well and keeps going at a more than reasonable speed. She's tolerant of changing conditions. Of course, on a race like the Vendée Globe, you have to hold on for the long haul and take longer naps than on a Route du Rhum, and the boat has to keep going fast even without trimming.

What did the team work on during the summer boatyard after the New York Vendée?

We machined the bulb, we did thousands of things. We redid some performance modifications. We had received the sails before the yard, so we were able to work on the Vendée Globe sails. We reviewed the ergonomics, installed a different mattress following the two transatlantic races, made minor modifications to the electronics and fittings... We worked in all areas.

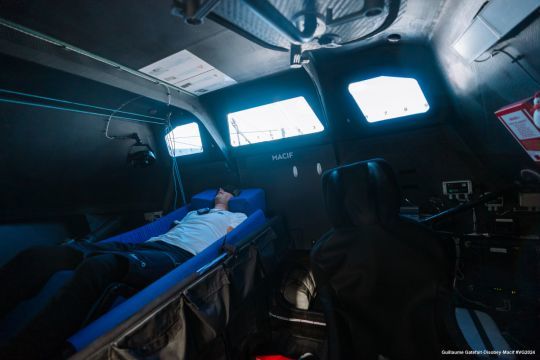

The configuration of the studette has been optimized for long solo voyages. Can you tell us how this has influenced your day-to-day management of life on board, particularly in terms of rest and navigation?

The good thing is that the card table is less than 1 m from my sleeping area. It's easy to switch from one to the other. It's instantaneous and effortless. The same goes for cooking. As I'm sitting on the map table for the journey and routing, I make my own food. I don't have to put on my oilskin, I'm freer than in the living area. There's no sea spray, so I don't need to get dressed.

We've made a lot of progress compared to Apivia in terms of aeration. This allows us to manage the temperature of these zones. By closing certain zones, I can create a draught or not. I can lower or raise the temperature in cold areas and keep the heat in those spaces. That's good too.

The space is small, so I have very few moves to make. When you have to cover a small distance at 30 knots in 3 m of waves, moving around is complicated. In this small area, it's pleasant, I make small movements, which avoids the risk of falling and uses less energy. If I'm upside down, all I have to do is lift my head off the bench to see the screen, and I've got a mouse next to it. It works well and it's pleasant. Life on board requires less energy. It's more functional than before.

How do you see the role of skippers evolving in a context where technological performance is becoming increasingly important?

It's all the more important. Boats are physical. It stings to go faster, so you have to be more physically ready, more enduring. There's a very high potential for speed, so you have to be careful in certain conditions. You can sail beyond what your equipment can handle. Just as in multihull sailing, you have to take your foot off the gas, and that's what IMOCA racing is all about. It's your sense of seamanship and feeling that will make the difference. Even if on foilers, there are sensors in every direction. You have to know if you're on the right side of the line, and not beyond the limit of the boat. That's what we're going to have to listen to.

We're not just ultra-technology operators. You have to know if what you're asking of the boat is reasonable. You could very well pull hard on a section and end up unscathed, but damage parts and break later. You have to know the difference, know how to listen and ask the maximum from the boat without going over the limit or damaging the equipment in the short and long term.

It's a long race, and we're all going to be tinkering. The parameter of wear and tear really comes into play. That's not the case on a Route du Rhum, where you might break something, because it's a short race. Parts are stressed for weeks, months... The climb back up the Atlantic is the hardest, because the boat is simply worn out. What could break may have, but when you go up the Atlantic, the parts break through wear and tear. Only the skipper can tell if the rhythm is right or not, and have the right feeling to know if you're at the right pace or over-revving.

Apart from the victory, what do you consider to be a success in this edition of the Vendée Globe?

It's always a success to finish, because it's a long race and a lot can happen. Leaving Les Sables and bringing the boat back to Les Sables, non-stop and without assistance, is a great achievement in itself. I'm going for the sport, to do better than last time, to be happy with all the choices we've made, not to tell myself that we made a mistake at this or that level. The ranking is quite important. Even if I've improved, the level is high.