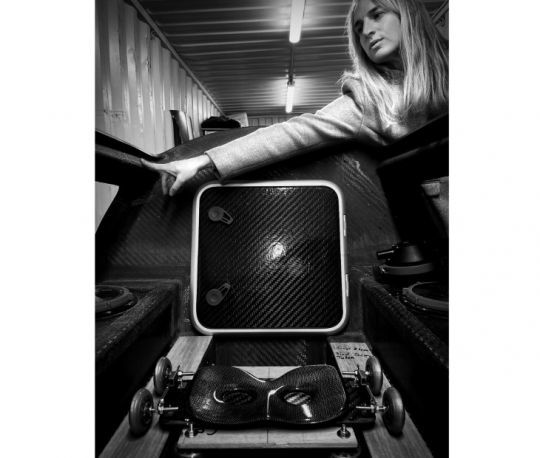

Building ReVenge, a lightweight carbon prototype, represents a triple challenge for Emmanuelle Guillerm: meeting a technical challenge, honoring the memory of her mentor Hervé Lalanne, and attempting to beat the record for crossing the Atlantic by rowing boat. Between stability tests and mental preparation, every detail counts before the great adventure scheduled for next January. In this second part, she reveals the essential stages of this achievement.

What technique was used for construction?

This is known as carbon infusion or vacuum lamination. In this method, a carbon fabric is placed on the surface and impregnated with resin. This is followed by a peel-off fabric, perforated plastic and felt to absorb excess resin. The advantage of this technique is that it avoids any excess resin, guaranteeing the lightness of the part. Once the felt is in place, it is covered with a tarpaulin glued to the support, then evacuated with a pump. Under vacuum, the excess resin is evacuated, leaving only the quantity needed to structure the piece. Between the technical and financial support I've received, and the guidance I've managed to put in place, I'm confident. But there's still a lot of work to be done before the crossing.

What are the current challenges?

ReVenge is a very light boat, made of carbon sandwich, weighing in at 230 kg empty, whereas similar wooden boats weigh 540 kg. It is therefore more vulnerable to overturning. I'm working with ENSTA to stabilize the boat in heavy weather. At the Fêtes maritimes in Brest, when I talked about stability, several people offered to help me. I was contacted, and set up a working group. We now work together on photogrammetry, modeling and stability calculations.

The aim is to find the best solution, and we plan to carry out tests in a tank. We'll load the boat with the weights it will have during the crossing, then move these weights around to see when it starts to turn over or fill with water. We'll calibrate the models in real life. I've had a bit of trouble finding a tank, as Ifremer's deadlines are complicated. I'm in the process of checking with Thales and there's also the École Navale, but this will involve a cost. The idea is not to weigh the boat down with ballast, as I've been working for 3 years to optimize its weight. It already has two 50-liter ballast tanks under the rowing station, which means it can balast at 100 kilos with water. The idea is to add load-bearing surfaces. We're thinking of adding these planes at the stern, at the fenders, at the oarlocks.

In terms of preparation, how do you go about it?

I take part in sessions to counteract any seasickness I may experience during the crossing. I don't often get sick at sea, except in very difficult conditions such as beyond force 7 Beaufort. So I decided to follow a preventive program. This takes place at the HIA (Hôpital d'Instruction des Armées) in Brest, which has a specialized department to deal with this problem. Originally intended for sailors, it is now open to ocean racers and the general public. A desensitization platform is offered here, and is proving a great success. You sit in a seat with a virtual reality helmet that simulates realistic maritime conditions. You see waves and beacons, and have to make specific movements with your head to cut off your bearings. What bothers me most is the desynchronization between the images and the movement of the seat, which ends up triggering the first signs of seasickness in me. Fortunately, I didn't vomit, but I felt really sick for the next 2 hours. It's an experience I'd recommend to anyone suffering from seasickness.

Although I've already crossed the English Channel several times and sailed the Transgascogne, this adventure will be my first transatlantic. It will be a first for me. As far as the rowing trials are concerned, I've mainly been training in Brest harbour. My crew member, Patrick Favre, took the boat off the coast of Portugal, from Lagos, to test conditions similar to those in the Atlantic. It was during this trip that we realized that the boat lacked stability. We therefore decided to return to the shipyard to make some modifications, and we hope to be able to test the boat again soon. The departure is scheduled for January, if all goes according to plan of course, otherwise it will be delayed. Personally, I can't wait. I've been working on this project for 3 years, and I can't wait to prove that Hervé was right in wanting to build a carbon boat. It will be a world first, because although some boats are partially made of carbon, there is as yet no boat entirely made of carbon for a solo crossing.

I also have a coach who manages my mental preparation. At the same time, I continue my work as a marine biologist at the Labocéa laboratory. I try to reconcile everything, which isn't always easy, but I'm lucky to have a manager who is also a sailor and understands my commitments. For physical preparation, I'm still lacking funding. I'm currently looking for funding, both for the new stability work and for this famous physical preparation, which is essential. In the meantime, I'm on my own. I'd tried indoor rowing for a while, but it was a bit depressing - I felt like a hamster in a wheel. So I diversified the sports I liked. I also do a lot of sailing. It's true that, basically, that's what makes me tick. I love being at sea.

I hear you're an expert sculler?

It's true! My father had a small fishing boat and taught me to sail from the age of 6. For him, it was essential that I mastered it. He was adamant that I should be able to scull the boat without any problems, a bit like learning to ride a bike. Today, it's a matter of course. I've passed on this knowledge to my children, who also go sailing. It's also practical in terms of safety when you're at sea. Sometimes the unexpected happens: engine breakdowns, lack of wind, but with these skills, you can get by. Sometimes, all you need is a bit of oar power to manage on your own!

/

/