Building the most powerful ship in the Baltic Sea

At 17 e in the 19th century, Sweden was an important European power. King Gustav II Adolf, nicknamed the Lion of the North, signed a contract with the Dutch master carpenter Henrik Hybertsson and his associate Arendt de Groote, for the construction of 4 new ships. In the fleet, the Vasa will be the most powerful ship in the Baltic Sea, if not in the world.

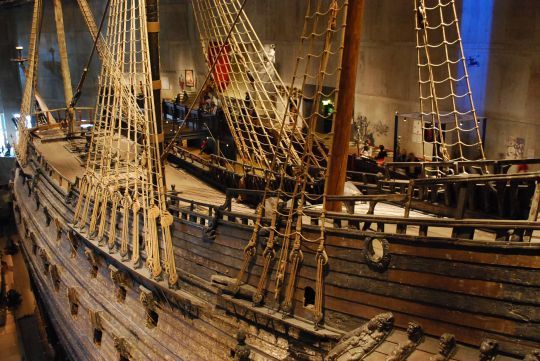

More than 400 people, carpenters, joiners, sculptors, painters and other craftsmen are busy building the boat. She is 69 m long overall, and more than 59 m high, from the keel to the top of the main mast. The ship weighed more than 1,200 tons once its 10 sails were rigged, carried 64 cannons and 120 tons of ballast. Hundreds of sculptures adorn her deck and hull.

The keel was laid at the end of the winter of 1626 at Skeppsgarden, the Stockholm shipyard in charge of the construction. Henrik Hybertsson fell ill and entrusted the end of the project to his assistant Hein Jakobsson and died barely a year later. He will never see his boat leave the Swedish port

A first alarm bell

Work continued for another year and the ship was prepared for its first voyage in the summer of 1628. One day, while 30 men were on board and wandering around the deck, the ship rolled alarmingly. The captain supervising the construction of the Vasa, Söfring Hansson, alerted Vice-Admiral Klas Fleming, who decided to stop the preparation of the ship for fear of seeing it sink at the quay. But the pressure from the king to launch the voyage was such that the Vasa undertook its first and only voyage a few months later.

A departure without return

On August 10, 1628, the huge ship left the quay of Château Tre Kronor under a salvo of cannons with 150 crew members on board. 1 mile further, still in sight of the shipyard where she was born, the gales shook the ship's mature body. The Vasa tilted to port under the gusts and water gushed out of the open ports. In a few minutes, the ship disappeared, taking with it 30 to 50 of the crew members, under the eyes of thousands of inhabitants who witnessed the scene.

Poorly thought-out construction plans

The king was warned and an investigation was launched. The ship's officers claimed their innocence. As for the builders, they explained that they had followed the plan approved by the king. The experts' report showed that the hull was too small to support the huge rig. The blame fell on the architect, Henrik Hybertsson, who had not been able to find the right proportions. Unfortunately, he had been dead for a year and could no longer be punished.

At 17 e in the 19th century, stability calculations did not yet exist. It turns out that the ship's center of gravity was too high above the waterline, its rigging being too heavy and imposing. It could not right itself when the gale made it heel.

The Vasaeuros must be saved

Numerous attempts were made to refloat the ship over the years. However, the ship was firmly embedded in the mud of the harbor. Between 1663 and 1665, 35 years after the sinking, a team of divers led by Albrecht von Treileben and Andreas Peckell managed to raise almost all of Vasa's cannons. They used the diver's bell, a recently developed invention that allowed them to reach the ship and extract the cannons, which were sold abroad.

In 1920, two brothers from Oskarshamn, Simon and Leonard Olschanski, requested permission to salvage pieces of wreckage from the Stockholm harbor between Beckholmen, where the Vasa was located, and Tegelviken. They planned to blow up the wrecks to recover black oak, a waterlogged wood, highly prized in Sweden for Art Deco furniture. But the authorities refused.

5 years to refloat the ship

Anders Franzén, a fuel engineer, has been interested in the wrecks of the Stockholm archipelago since his childhood. During the summers of 1954 and 1956, he located the Vasa thanks to documents dating from the 17th century e century. He used grappling hooks that he swung from a motorboat to find the wreck. On August 25, he was searching with the diver Per Edvin Fälting, in front of Beckholmen Island, when his grapples finally caught the wreck.

The refloating started in the autumn of 1957. 6 tunnels were dug under the ship to run steel cables, connected to two pontoons which were used to lift the ship. On August 20, 1959, the pumps started and the Vasa was freed from the mud. The ship was lifted and moved under the surface of the water in 18 steps. In September, the ship was located at a depth of 17 m near the island of Kastellholmen. The divers will spend another year and a half preparing the ship for the final lift.

On April 24, 1961, the ship was raised from the bottom, along with 14,000 wooden pieces. Everything was kept separate, before being reintegrated into the various parts as they were removed.

On February 16, 1962, the ship was ready for public display at the newly built Vasa Shipyard. Visitors could view the ship while conservators, carpenters and other technicians worked on its restoration. In 1962, 439,300 people bought a ticket to see the wooden work of art rise from the water.

Keeping a wooden ship of 1200 tons

Rebuilding and preserving a mighty 17th century warship is an enormous challenge. As waterlogged wood dries and the moisture it contains evaporates, it shrinks and cracks. To maintain the integrity of the vessel, scientists use polyethylene glycol, PEG, to replace the water. Bulk objects are placed in large baths, while the ship's hull is sprayed 24 hours a day, using 500 nozzles and an elaborate pumping and filtering system. This treatment continued until 1979.

Likewise, drying takes time to prevent cracking. Over the next 10 years, the moisture content gradually decreases. It takes several decades for the vessel to fully stabilize.

Birth of the Vasa Museum

A museum dedicated to the ship and naval life of the 17th century e century was built in 1981. But too many visits increase the humidity of the room. Combined with the sulfur in the wood, it creates destructive acids. The Vasa is once again in danger. In 2004, a state-of-the-art climate control unit was installed to maintain a temperature of 18 to 20° and to study the functioning of the wood. Today, more than 98% of the ship's structure is original, including the masts and sails. It is the ship of the 17 e century the best preserved in the world.

In 2018, the museum is undertaking a 7-year effort to change the 4,000 rusted iron bolts. Now 8 tons lighter, these new corrosion-resistant steel bolts also reduce the risk of chemical reaction in the wood. Today, the Vasa is still being researched by experts from around the world.

/

/