The law of the sea is governed by a myriad of texts and conventions. The law of rescue at sea is more lightly regulated, mainly by two texts. The 1974 SOLAS (Safety Of Life At Sea) Convention on the one hand, and the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the other.

Legal obligations

What does the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea require of us?

Article 98 of the Act provides that :

- Each State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag to ensure that, so far as is practicable without serious risk to the ship, the crew or the passengers :

- He assists anyone found in, peril at sea..

- It shall come to the assistance of persons in distress as soon as possible if it is informed that they are in need of assistance, insofar as it may reasonably be expected to do so

[...]

- All coastal States shall facilitate the establishment and operation of a permanent, adequate and effective search and rescue service to ensure maritime and aviation safety and, where appropriate, cooperate with their neighbours in regional arrangements to this end. "

In other words, as soon as a mariner becomes aware of a person's distress at sea, he is under a legal obligation to promptly go to the persons in danger and render assistance.

Common sense and brotherhood above all

As is the case in the Vendée Globe, it is obviously not necessary for a race direction to order one sailor to go to the rescue of another in order for the latter to do so. Common sense at sea, the brotherhood of the people at sea is enough for this initiative to be taken without questioning the risks that may be involved.

Counter-examples exist

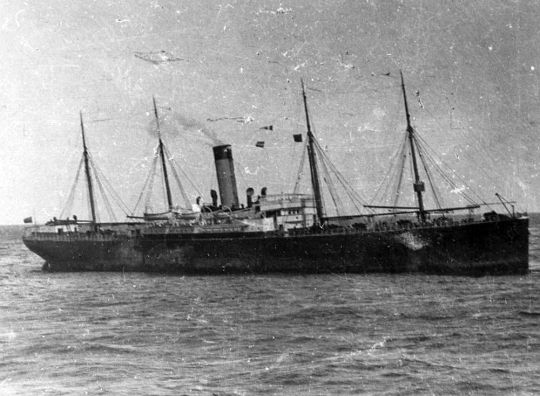

It is also because some, driven by other more personal or commercial interests, do not respond or pretend not to hear distress calls from other buildings that it was necessary to design these regulations. The best known is undoubtedly the case of the Californian, who is said to have been able to assist the Titanic when it sank in the middle of the Atlantic in 1912.

A race within a race

However, the fact of assisting another navigator, whether it is a legal or moral obligation or a requirement of a race direction, represents a race within the race. All the more so when the life raft has been struck. It is the meteorologists' extensive knowledge of currents and winds on the one hand, and on the other hand, the engineers' knowledge of liferaft drifting on the other, that makes it possible, based on the liferaft's launching area, to calculate, from hour to hour, the estimated position of the liferaft's life-saving appliance.

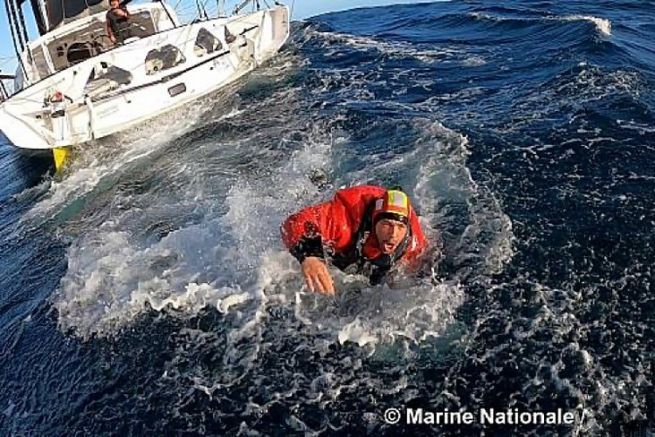

They do it with Swiss precision. Jean Le Cam was 1.5 miles from Kevin Escoffier when he spotted his raft and Kevin Escoffier will have travelled only 7.05 miles from the point where his beacon was triggered to the point where it was recovered by Jean Le Cam.

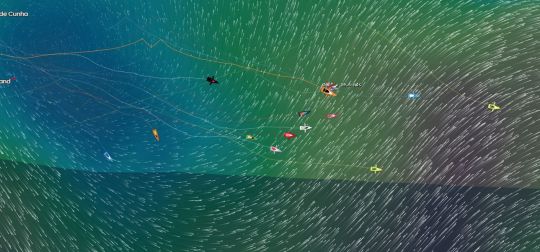

The report to the mapping of this rescue is rich in lessons learned. At 1430 hours (Paris time), when he triggered his beacon, the skipper of PRB was experiencing winds of 22 knots blowing from 246°.

At 1900, it passed 229° at 23 knots, then stabilised at around 206° at 0300 on 1 December. It was therefore a north-northeasterly wind that brought the navigator to the point where he was picked up on Yes We Cam, north-northwest of the place where he triggered his beacon ( Place of activation of the escoffier beacon S40° 55' 0'' E9° 15' 0'' Browser recovery location S40° 48' 7'' E9° 13' 0''), by the combined effects of wind and current drift.

Global Collaboration

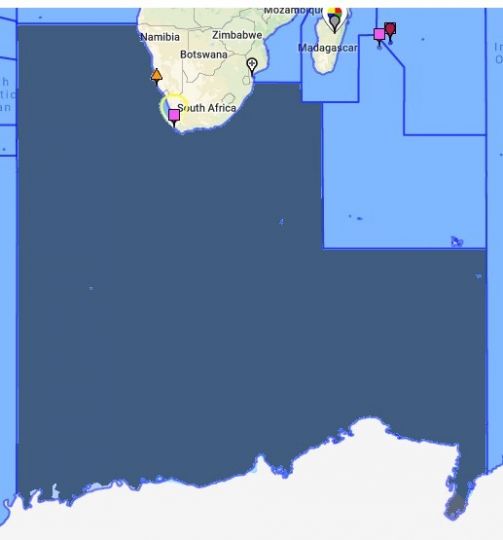

The authority responsible for organizing this rescue was the MRCC in Cape Town, South Africa, whose authority extends from Namibia to Mozambique, along the southern cape of Africa in the North, to Antarctica in the South.

When Escoffier's EPIRB beacon was triggered, the call was received by soldiers from CROSS Gris-Nez (France), which is part of the SaR system ( Search and Rescue ) worldwide. It was quickly forwarded to the authorities in South Africa, the manager of the area. It is in this capacity that this country is responsible for the organization of relief efforts in the area. The staff of the centre in France is therefore at the disposal of the remote authority to study the means that may be available on the spot, if necessary. In the same way, moreover, as all SaR member countries. The South African rescuers will, in particular, have contacted the US Army to check the possible presence of a building in the vicinity of the trigger zone. The same applies to any Navy vessels potentially in the vicinity. Throughout the operation, the CROSS military will have been in contact with the Race Direction every 10 minutes to keep the information channels open and up to date, both up and down.

The earth leads the way

Functionally, the skippers are remotely controlled from land, by the race direction (which allows them to exchange in French with people they already know) to get to the zone. All this is managed by the local rescue authorities (MRCCs for Maritime Rescue Coordination Centres such as CROSS in France) who make sure that they deploy the necessary means and only them, so as not to create a situation in which the rescue organisation would become uncontrollable. It is easy to imagine the impossibility of succeeding in a rescue if, for example, two boats are, at the same time, trying to approach the raft.

Desynchronize arrivals on site

For this reason, diversions are never ordered simultaneously. In the case of the 2020 Vendée Globe operation, Jean Le Cam was first of all diverted to go to the zone (he was the closest), then Yannick Bestaven and Boris Herrmann were also called in to complete the search. Finally, Sébastien Simon will be sent on site. A zone thus squared by 4 boats, arriving at different times. These diversion instructions will have been issued by the MRCC in Cape Town.

Need for coordination

The strategy of a single organizer (CROSS in France) of the actions is the only one that is efficient, it allows monopolizing the indispensable actors and them alone, maximizing the chances of success of the operation whose central objective is, let us recall, to preserve the life of the person in danger on the water. This is the reason why, as a yachtsman, we must not under any circumstances intervene in a disaster without notifying the authorities (canal 16), except to ensure that we do not disturb the action already underway.