Jean-François Joubert, a native of the Léon region, met the owner's son. It was his father, Doctor Jacques Perron, who ordered the construction of this boat from the Le Got shipyard in Plouguerneau in 1962. The surgeon wanted a boat for cruising. So he ordered one with a deckhouse and, above all, one that was larger than the classic goémoniers. Indeed, the open canoes used to collect seaweed were usually between 5.50 and 6.50 m long. The Reder Mor 6 measures 7.80 m.

Seaweed harvesting consists of gathering seaweed under the sea. In the past, this seaweed, which once ashore was transformed into blocks in ovens, was then delivered to factories on the mainland to extract iodine (for pharmaceutical use in particular).

To be weighted down, these seaweed boats took on board pebbles, which they threw back into the sea, replacing them with seaweed as they fished. No pebbles on the Reder Mor 6, but a piece of cast iron bolted under the keel.

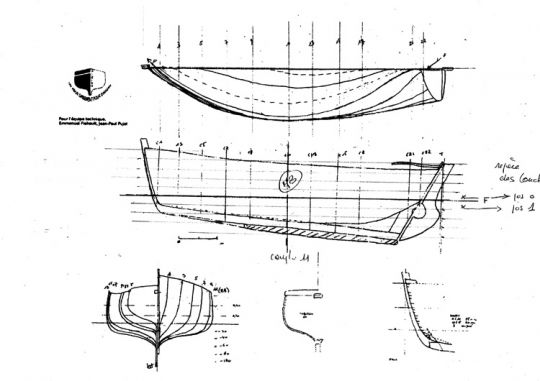

All that remains of the original is the keel, ballast, top of the stem and 5 spars... everything else is new, rebuilt as it was then, using solid wood with mahogany and oak planking and iroko keel.

Emmanuel Flahault, president of the association Un Vieux Gréement pour Damgan, presents the Reder Mor 6 renovation project

On February 6, 2015, the Reder Mor 6 arrived at the Penerf shipyard in very poor condition. Why did you decide to restore her?

Emmanuel Flahault: Yann Réveillant, the association's first president, initiated the project. He was able to unite around him a small group of passionate volunteers, convinced of the importance of saving this boat. The Reder Mor 6 was acquired and transported to Damgan-Penerf. It seemed unthinkable to us to leave such an important part of the local maritime heritage abandoned. And let's face it, the human and technical adventure involved in the restoration was simply irresistible.

The first year was devoted to structuring the project: we had to set up the association, prepare grant applications, ask for quotes, devise a mode of operation, and find suitable premises and the necessary machinery. It all required a great deal of effort and organization.

The shipyard was open one day a week, on Thursdays. A professional marine carpenter, paid by the day, was regularly on site. Volunteers took charge of supplies and purchases, and played an active part in every stage of the restoration.

Three years of restoration, plus the search for funding: you're tenacious! What were the most critical aspects of the project?

Initially, when I was appointed site manager, I envisaged a more modest project, with a reduced budget and an estimated work duration of between one and a half and two years. But very quickly, we realized that the scale of the restoration was far greater than anticipated. In the end, only a few original parts were preserved: the keel, five spars, the bitt, the top of the stem, the porpoise, the fittings and the rigging.

The overall budget was ?145,000, a daunting figure. Fortunately, the Chairman and the Board of Directors were fully mobilized to secure the financing. For our part, we all jumped in with gusto. The use of volunteers enabled us to reduce costs by around ?40,000, which was far from negligible.

On the site, work was carried out in a pleasant atmosphere. On the other hand, taking part in various local events, particularly in Damgan, sometimes proved to be more demanding. Catering, refreshment stands, sales of by-products... these activities kept us very busy during the summer months.

The educational workshops were also very active: models, seamanship, and above all the activities carried out with schools. They were time-consuming, but reinforced our visibility â?" an essential element in obtaining funding. These exchanges with children were particularly important to us. Classes came regularly to visit the site, and for us, these moments of transmission were a great way of opening up to young people.

Today, the association has almost a hundred members. We also enjoy invaluable support from local businesses. The atmosphere oscillates between that of a group of friends and that of a team of experienced professionals. The vast majority of our members are retired.

But without our marine carpenter, François Blatrix, we would have been at a loss. He agreed to work with us, paid by the day, while giving us precise advice on the purchase of wood, screws, glues, sealants and tools. François had a perfect grasp of the spirit of our association: he knew how to encourage, reframe and pass on. Demanding and passionate, he was a remarkable professional.

His background spoke for itself: he had helped rebuild the Saint-Michel II replica of Jules Verne's ship, and was also in charge of the Forban du Bono of Our Lady of Béquérel and many other traditional boats. A sailor at heart, he loved to take to the sea aboard these old rigs.

/

/