Characteristics of a junk sail

- Mast(s) are self-supporting

Unlike Bermudan rigging, which is heavily guyed with enormous compressive forces on the mast and standing rigging, junk rigging masts are self-supporting and work like fishing rods or Laser or cat-boat masts. The mast works by bending and absorbing shocks or gusts. The sail is not blocked by the shrouds, and can be broad-sailed at downwind speeds. - It's a one-third sail

The sail is suspended from a yard that extends out in front of the mast. The rocambeau is replaced by a common maneuver called the cravate, which brings the yard to the mast. - A fully battened sail

The sail is divided into independent panels held together by battens. Each batten is attached to the mast by a batten strap. Forces on the sail are transmitted directly to the mast by the batten straps. - Each batten is connected to the listening system

Unlike a Bermudan rig, the boom plays no special role - it's just another batten. Each batten is connected to the sheeting system, either directly or via a more or less complex pantory system linking several battens. Forces are distributed along the entire length of the leech, and the sail's twist is perfectly controlled. The forces on the sail are distributed between the various panels. - Canvas and slats are held in place by Lazy Jacks

Lazy Jacks, which have become a standard feature on Bermuda rigs, originate from junk rigging, where they have been used for hundreds of years. When the sail is reduced or lowered, the canvas, held in place by the battens, stows itself in the Lazy Jacks.

But what are the advantages of junk rigging?

- It's an easy, reassuring rig.

The sail is often made up of 5 to 7 battens, each equipped with a sheet, connected to the others by a network that brings them together to form a single sheet in the cockpit. Tension is thus distributed over the entire sail. The leech is maintained during tacking and gybing. The sail does not flap in the wind, and changes tack smoothly.

With its low center of sail, a junk-rigged yacht doesn't heel much, so we reduce sail before the liston is in the water. - Manoeuvres as simple as on an Optimist.

With no headsail and no standing rigging, maneuvering is as simple as on an Optimist.

To tack upwind, push the tiller in and wait for the sail to set on the other tack.

To gybe, you pull in the tiller, the sail comes under the false tack and, as the leech is held all the way, the sail will pass in one go, once straight under the false tack, to find itself virtually unstuck on the crosswind under the other tack. All that's left to do is lower the sail under the new tack to get back on course.

- Lack of effort.

The multiplicity of sheets and battens distributes forces throughout the sail, which never feels "forced". The luff and leech are not strained. A junk sail always works smoothly. A self-supporting rig works by bending, like a fishing rod. - Canopy adaptation is instantaneous.

When the wind picks up, reefing simply involves letting go of the halyard, and lowering one or more sail panels into the lazy-jacks. Each panel is delimited by a batten, so a 5-batten sail can be reefed 5 times. It's not even necessary to reduce entire panels. Once the sail has been reefed, all that's left to do is to take up the slack again. Next, but without haste, we take up the cravat to bring the yard back towards the mast.

When the wind drops, the reverse operation is just as simple. Release the tie and ease the sheet a little. Take up the halyard, sheet and tie, and you're done! Either of these manoeuvres usually takes well under a minute. And best of all, it's all done from the cockpit, without even changing course!

The ease with which you can reduce or increase the sail area means you always have the right sail area for the conditions at hand. You can go from the power of a spinnaker to the safety of a storm sail in a matter of seconds. You no longer have to preventively reduce sail area or sail under canvas because the wind has weakened.

You no longer have to work on the sail's power with the halyard, the foot, the sheet, the clew, the cunningham... All you have to do is adjust the sail area instantly to get the best sail for the time.

When modifying a Bermudan-rigged boat into a junk, we take the area of the mainsail and genoa as the reference area. This is increased by 30% to establish the surface area of the junk sail: this gives a power margin for light airs. - Sail longevity.

Imagine a tear in the mainsail of a Bermuda rig. It immediately renders the sail unusable.

As a junk sail is divided into several panels bounded by battens, a tear in one panel does not affect the rest of the sail, which continues to be usable. We've seen junks with tattered sails continue to sail.

When you have a tear on a junk sail, it doesn't spread. We simply patch it with a piece of Insigna (or Grey Tape) at the next port of call.

When you break a batten, it's extremely easy to attach it to the batten above or below, leaving you with a permanent reef. A splint can also be attached to the batten using a gaff, for example. - Easy to install.

With less stress to bear than Bermuda sails, today's junk sails are made of lightweight fabric. Today's battens are mostly made of aluminum on larger boats, and of small-section wood on smaller ones. The sails are not stowed in a track on the mast, but slide freely along it. The light weight of these sails and the absence of friction make winches virtually unnecessary.

The mast is self-supporting, so forget about shrouds, cap shrouds, spreaders, turnbuckles and chainplates... and the dismasting associated with breaking one of these elements. All ropes are textile, and adjustments are simple to make.

- An economical rig.

As mentioned above, the self-supporting mast requires none of the expensive fittings that go with shrouds. Nor is there any need for winches, genoa furlers or multiple headsails.

The sail, which is subject to less stress and can remain operable even after it has been torn, can be made from low-cost canvas. The fabrics most often used are awning fabrics (Sunbrella type), which are appreciated for their resistance to ultra-violet rays rather than for their mechanical properties. Repairs are never expensive.

One penniless skipper even made a junk sail out of weed-proof fabric for green spaces. He made battens with two cleats on each side of the canvas, screwed together. All in one day! - Power downwind.

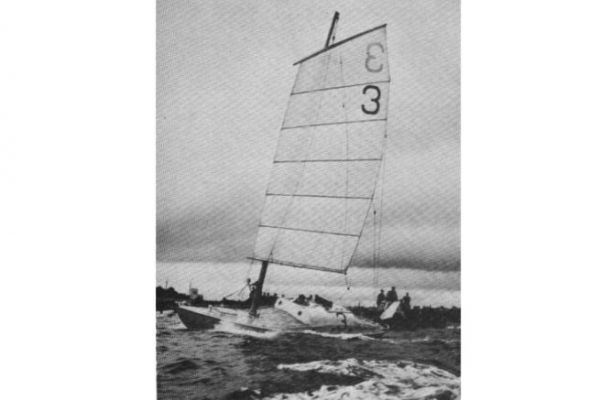

Easy reefing means you can carry a large sail at all times. The absence of shrouds and spreaders allows the sail to be overhung up to 90° from the boat's axis in downwind conditions, exploiting its full strength and equivalent to the power of a spinnaker, without the disadvantages associated with the latter. - Performance even upwind.

For the initiated, junk rigging has a reputation for limited upwind performance.

This is historically true, as the flat sail and soft battens result in a low-powered sail with a very shallow draft. What's more, junk rigs are often found on cruising boats that are very typical, heavy, with a shallow draft, long keels and even twin keels. These rigs do not favor upwind performance.

Even if counter-examples do exist, and we now know how to build junk rigs that perform well upwind. On the other hand, as soon as you drop a little, the sail area and low center of sail result in an overpowering rig with moderate heel. On hulls that don't glide, we reduce without slowing down, when the helm becomes hard because the boat has reached its hull speed and "stuffs" into its bow wave. These boats remain very lively downwind, even in light airs.

/

/