For centuries, yachtsmen and sailors have braved the seas, but shipwrecks are an ever-present reality. The history of lifeboats and lifesaving societies dates back to the 18th century, when ingenious minds began designing craft to save lives in peril.

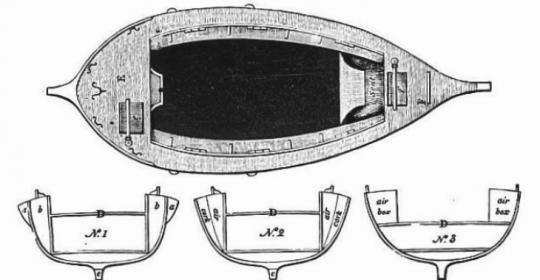

L' '' Unimmergible boat '', an experimental canoe

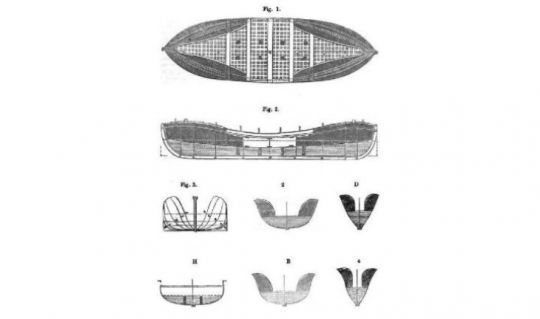

In 1784, English inventor Lionel Lukin began experimenting with a technique to make a 6.1 m Norwegian yawl unsinkable. He incorporated air pockets into watertight bulkheads, using cork and other lightweight materials in the structure. An iron keel adds weight and helps maintain stability. After testing his alterations in the Thames, he patented his method of building small boats that wouldn't sink, even when filled with water.

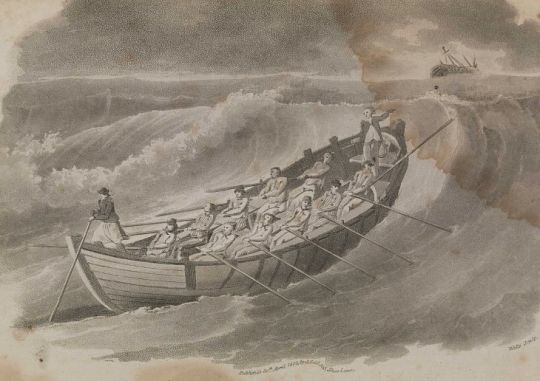

Tragedy as a driver of innovation

Since 1785, only smoke boxes have been used to revive asphyxiated shipwreck victims at customs posts near ports and waterways. A period book tells us the contents of a smoke box: '' This box must contain the following items: two flannel rubbers; a woollen capâeuros¯; a woollen blanketâeuros¯; two bottles of camphorated brandy, animated with fluorine alkali, or volatile spirit of ammoniac salt; a pewter beaker; a mouth cannula, with its skin pipeâeuros¯; a small tinned iron spoon; a bottle of fluorine alkaliâeuros¯; a box containing several packets of emmetic, three grains eachâeuros¯; the body of the fumigatory machineâeuros¯; a single-blade bellows, to be fitted to the machine; four rolls of smoking tobacco, fifteen decagrams (half an ounce) eachâeuros¯; tinder, a lighter and a box of matches; feathers to tickle the inside of the nose and throat; two bleeding strips .'' This medical invention, designed to save drowning victims by inserting a bellows and a small amount of tobacco into the rectum of the dying person, would then act as a defibrillator. At the time, respected physicians such as René-Antoine de Réaumur were firm believers in this method.

Faced with somewhat dubious rescue resources and an upsurge in devastating shipwrecks, awareness has grown of the need to invest in more effective marine rescue resources.

Following the sinking of the Adventure in 1789, in which the entire crew perished, a lifesaving competition was launched. In 1790, Henry Greathead presented his Original, a model that proved more effective than Lukin's. Measuring 8.5 meters in length, the Original could accommodate twelve people, for whom cork jackets were provided. Its main quality is that it is unsinkable, thanks to an interior cork lining and the addition of a cork fender belt. This design considerably increases the boat's buoyancy, enabling it to right itself quickly after an overturn. The Original has a curved keel and a higher silhouette at the bow than at the stern, making it highly maneuverable around its center. When full of water, a third of each end remains out of the water, enabling it to continue on its way without sinking. It is propelled by ten short oars, better suited to rough seas than long ones. Steered by oar rather than rudder, it can move in either direction. After proving its worth on the Tyne in England, the Original is designated the first specialized rescue boat. Thirty-one other replicas are built.

Self-righting canoes

At the same time, William Wouldhave, another inventor, takes part in the lifeboat design competition alongside Henry Greathead. His idea was to create a self-righting boat made of copper, with cork for buoyancy. His design was not approved by the judging committee.

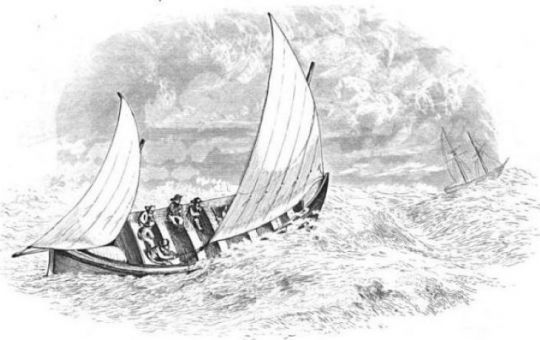

In the middle of the 18th century, several towns in the UK had different models of lifeboat. Some were equipped with a self-righting mechanism, and all had oars. In 1850, the Duke of Northumberland organized a competition to design a lifeboat capable of using sails in addition to oars, to extend its range. No fewer than 280 entries were submitted, with James Beeching's judged to be the best. So in 1851, with the help of James Peake, he designed the self-righting Beeching-Peake SR lifeboat, which became the standard model operated by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution around the coasts of the UK and Ireland between the 1850s and 1890s.

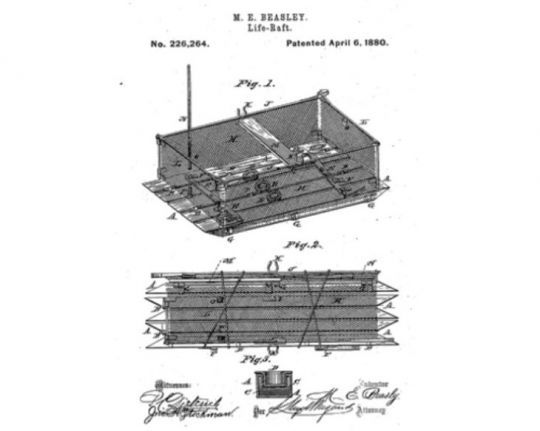

Around the same time, in 1880, Maria Beasley patented a compact, safe, easy-to-use and fireproof lifeboat. Beasley's folding lifeboats were used on the Titanic in 1912, when 4 were installed in addition to the 14 rigid lifeboats.

The years that followed saw the advent of numerous lifeboat models, gradually incorporating combustion engines. Today, several models are preserved and displayed in coastal rescue stations. Among them is the Aimée-Hilda, an unsinkable, self-righting lifeboat designed by renowned yachting architect Eugène Cornu, and built by the Jouët shipyard in Sartrouville in 1949.

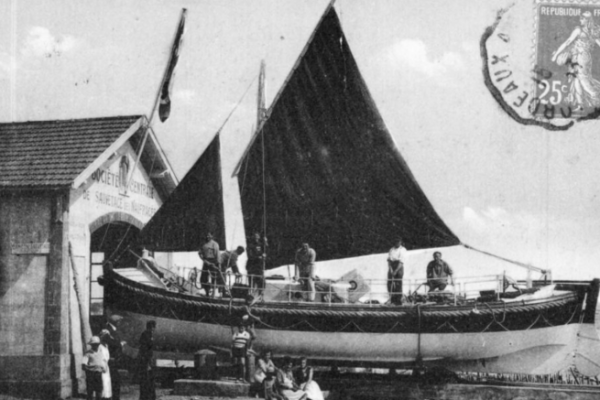

The emergence of rescue companies

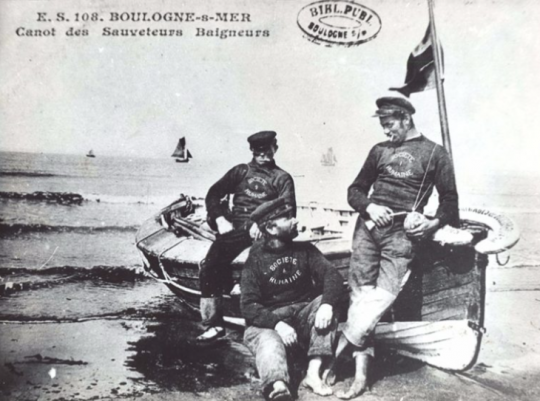

The 19th century saw the birth of industrialization. As maritime traffic increased, so did the number of accidents and shipwrecks. A few terrible shipwrecks made some humanists realize that it was time to move on from the role of grieving spectator to that of active rescuer. Lifesaving societies were born, financed mainly by donations and legacies. 1824 saw the creation of the ''Royal Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck'' in the UK; 1825, the ''Société Humaine des Naufragés de Boulogne-sur-Mer'', followed by that of Le Havre the same year; 1834, the Société Humaine de Dunkerque...

In 1834, the physician Calixte-Auguste de Godde de Liancourt founded the "Société Internationale des Naufragés", which set up rescue centers in several ports of the French monarchy, as well as in the rest of the world. It can also be found under other names: "Société Générale des Naufragés dans l'Intérêt de toutes les Nations", "Société Générale des Naufrages et de l'Union des Nations", or "Société Générale Internationale des Naufrages". By 1841, there were more than 150 international establishments.

The activities of the "Société Internationale des Naufragés" came to an end in 1841, following the creation in 1838 of the "Société Centrale des Naufragés", a rival institution set up at the instigation of André Castera, Administrator of the French Navy. This centralization marked the beginning of more efficient coordination of rescue operations at sea. In 1967, the latter merged with the "Société des Hospitaliers sauveteurs bretons" to form the "Société nationale de sauvetage en mer" (SNSM). This merger consolidated resources and optimized rescue efforts across France. Today, the SNSM heads a fleet of over 785 nautical resources, including 41 all-weather boats, 35 1st class launches, 75 2nd class launches, 42 light launches, 90 motorized watercraft (jet skis) and 473 inflatable boats, including 192 RIBs.

Volunteering is the cornerstone on which the SNSM's social missions are based: preserving human life at sea and on the coast, civil protection operations and raising public awareness of the dangers at sea. What if you too were to consider joining the orange family of Sauveteurs en Mer?

/

/