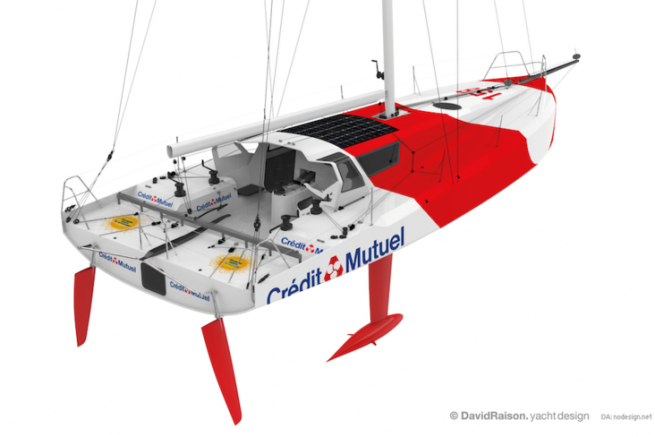

In the microcosm of ocean racing, we hear about scows that pulverize their opponents at certain speeds. These sailboats, so wide in bow, are astonishing and do not leave anyone indifferent, even unleashing passions about aesthetics. We will put this aspect aside and focus on the technique, because no matter what the skeptics like, we know that what performs always ends up being beautiful.

Being right before others

David Raison is a bold man. Almost 10 years ago, braving scepticism, he opened a breach by drawing an atypical racing hull, the scow. For those who have never seen it before, the scow looks a bit like a rusk with a sail. These hulls were very popular in the early 20th century on the American Great Lakes. These overpowered sleds were already on familiar terms with the 20kt on the schedule. I suggest you go to the bottom of the article to see a 1939 video featuring these spectacular sailboats.

David Raison had the brilliant intuition that these hulls could be adapted to offshore racing. As a visionary and reckless architect, he experimented and validated this hull in the Mini class. He designed, built and won the mythical transatlantic race himself aboard the first ocean racing scow.

For a decade, his mini 6.50 protos, the Magnum and then the Maximum - its evolution - won all the races in the Mini class at the hands of various skippers, including Ian Lipinsky, confirming the clear architectural advantage.

Some gauges limit innovation

Faced with this tour de force and the increase in power, some classes such as the Imoca and class40 quickly put in place measurement rules limiting the possibility of drawing a pure scow. The authorities argue that this is to avoid making a large part of the existing fleet obsolete in the face of a new generation. This is a laudable objective.

But then, why allow foils on Imoca?? Some people think that the technical advantage would be less than with the forms of scows. What is certain is that it is easier to install foils on an existing boat than to transform the shape of a hull.

In any case, David Raison does not ask himself the question of the relevance of the brakes set up by the classes, he wonders how to adapt his hulls to the gauge constraints. Indeed, according to him, the rules limit the freedom of drawing, but do not prevent us from getting closer to the scow effect. Moreover, he designed for Ian Lipinsky a Class40 which despite the gauge restrictions is almost a scow.

Would scouting be the best bateau??

David Raison explains some of the interests of a scout. "In ocean racing, we try to increase the power of our boats to go faster at all speeds. It means being able to wear more canvas, without having more cottage. In other words, we're trying to get more power into the hull. With scow we are everywhere at the maximum width, so we have a higher power, which surpasses the largest drag. In most cases, they are faster boats."

An inevitable evolution towards scouting?

Over the past two decades, architects have constantly flared the hulls to gain power. First, they widened the bridges by extending the main beam to the transom.

Then, faced with gauge limits on deck widths, the architects found a way to widen the waterline without widening the deck: draw much wider hulls and "cut as short as possible" all unnecessary dead works.

It was the reappearance and generalization of bilges. And after having proved their worth on all racing boats, these developments have also conquered cruise ships.

Today, a new generation of ocean racing boats is emerging and this nose is particularly remarkable, the scows.

Undeniable advantages

Indeed, it seems that we are at the end of the concept of power gain by the rear forms and David Raison explains the limits of this trend: "The problem is that by increasing the width at the back of the boats they become real triangles whose tip, the bow, tends to sink into the water at the lodge. Moreover, still at the gite, the keel axis is no longer really in the axis of the submerged hull. It's not ideal in terms of drag."

But we cannot help but think of the passage at sea of such a large bow. What does David think about it Raison?? "Actually, it doesn't do much good to have the bow in the water, I prefer it to be above it. The displaced water must go somewhere and rather than sending it to the sides, it goes underneath. With scow, you can send this power back under the hull and no longer have the bow sinking into the water."

On boats that often glide, it is necessary to change paradigm and think in terms of drag. What are the other advantages of these scow? hulls? "At high speed downwind, we want to raise the boats to limit the brakes. On scows, even at high speed the decks remain dry unlike current boats. In addition to the discomfort of sea conditions that can affect performance, when you take 500 kg of sea water from the deck at the bottom of the wave, it's a guaranteed deceleration."

The images of Imoca literally underwater speak for themselves. So this shape of hull must allow a higher average speed downwind.

And what about the power of carène?? "With the scow shape we are wider so more powerful, even if there are a few more brakes the power gain prevails. We gain 10 to 15% more righting torque, and that's considerable."

So when will we see the Imoca's measurement rules open up, and when will we see front cabins as wide as the squares of our sailboats at croisière?? sailboats from croisière? So when will we see the Imoca's measurement rules open up, and when will we see front cabins as wide as the squares of our sailboats at croisière??

Video de scow sur les Grands Lacs Americains en 1939 :