Committed for several years to raising environmental and ecological awareness in the world of ocean racing, the La Vague collective has joined forces with Véronique and François Sarano of the Longitude 181 association, the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW France) and WWF France to provide answers to the questions raised by sailors, yachtsmen and observers about collisions between boats and cetaceans. With the Ultim trimarans conceding several collisions with UFOs, possibly whales, on the Arkea Ultim Challenge round-the-world race, the harmful interactions of ever-faster sailing boats on marine wildlife are back in the spotlight. In 12 questions, the authors set out their arguments and possible solutions.

Can ocean racing slow down? Do the evolution of boats and mentalities go hand in hand? Here are 12 points from La Vague.

"An omerta, really?"

If there wasn't an omerta, teams would talk about it openly, and not try to hide the distribution of images. Off the record, in other past races, teams have admitted to finding a piece of cetacean on a keel sail, or even a cetacean embedded in a foil. Since we want to keep a clean image, and sponsors don't want to be associated with that image, we don't talk about it: so there's an omerta.

"There have always been collisions and there always will be"

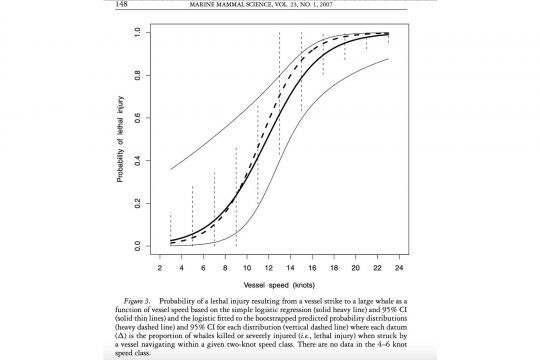

In the past, there were fewer collisions because boats were slower and raked less surface area. Studies on commercial vessels indicate that between 10 and 15 knots of speed, the probability of killing cetaceans increases dramatically (Vanderlaan & Taggart, 2007). Work is underway to adapt these predictions to racing yachts.

The surface area covered by foils is a problem shared by several classes of racing boats (mainly Ultimates and IMOCAs). For example, if we compare a 2023 Ultim trimaran with a 2015 Ultim trimaran, this surface area has been multiplied by 5, as foils are getting bigger and bigger.

"Cetaceans can hear for miles and anticipate boats"

Whales have been living in the ocean for millions of years, yet the advent of fast sailing and motor boats is relatively recent. As a result, they have not had the time to evolve and adapt to these new threats.

So no, foilers are so fast that cetaceans don't have a chance to see or hear them coming.

"Technology will solve the problem

It's a total headlong rush. Waiting for a new technology to solve a problem created by the first technology is a deleterious spiral. The Oscar radar (designed to detect floating objects) is currently being developed, and may help with certain solutions, but it takes time and will never be 100% effective. Results are very limited at high speeds for detecting a nearby submerged object or animal. It would simply be simpler to slow boats down.

As for pingers, their repellent effect is not guaranteed, according to bio-acoustics specialists. What's more, a pinger can act differently from one species to another.

They also reflect an anthropocentric vision of the world, as if the sea belonged solely to humans. We rake the whales' living space with gigantic razor blades. Adding pingers would mean shouting loudly while continuing to rake their living space with these razor blades. Is this really a desirable solution?

"It's not offshore racing that kills the most whales"

A classic argument for inaction, it's called whataboutism. There are worse things elsewhere, so it's not up to me to change. Among cetaceans, every individual counts. Some species are still in serious danger of extinction.

With the number of boats on the water constantly on the rise, increased noise pollution disrupting their movements, ocean acidification, chemical pollution, dwindling food resources and overfishing, it's easy to understand that anthropogenic pressure is terrible for cetaceans. Everything must be done, everywhere and at every level, to protect these species.

Collisions with ships are the leading source of unnatural cetacean mortality, yet they are almost invisible: most of the time, the animals' bodies sink to the bottom of the ocean. The media coverage of ocean racing, and the visibility of accidents between racing yachts and marine animals, helps us to realize the scale of the phenomenon. The 60,000 cargo ships that ply the oceans are responsible for the death of many animals and the rarefaction of certain species. We can also draw inspiration from the solutions deployed in New Zealand and North America, where limiting the speed of commercial vessels has saved several whale populations from extinction.

"Can the skippers see if the collision was with a cetacean?"

Obviously, no skipper, sponsor or race organizer wants to have a collision. It shatters an animal's life, it stops a race.

Cockpits are increasingly closed. And very often, it's only after the impact, by looking at the wake, that we can possibly understand the origin of the impact. The racing organizations now make it compulsory to report any collision or encounter with a cetacean. But as I said earlier, nobody wants to be associated with these tragedies. On the other hand, an expert examination when the boat comes out of the water could help to establish the nature of the collision. Pieces of skin are sometimes found, while in other cases, splinters and damage to the boat may indicate the nature of the objects or organisms struck

"There is more risk of collision with macro-waste than with cetaceans"

Although absolute figures are difficult to obtain, it seems that the vast majority of collisions at sea are with marine animals, including cetaceans. Scientific observations point in this direction, and La Vague's sailors make the same observation in their sailing experiences. It's rare to come across macro-waste such as containers or logs in the middle of the ocean. In fact, we often hear of sailors encountering whales, but never containers.

And again, if speed wasn't so high and boats were sturdier, hitting a piece of wood shouldn't break a boat.

"If we listen to the ecologists, ocean racing has to stop, let us dream!"

How about reversing the paradigm? What if our dream is to still have whales in the ocean? It's these fast-moving boats that bother us. One person's freedom ends where another's begins. And we humans are going much too far against the freedom of life of ocean species.

"We have to stop picking on ocean racing and skippers"

Because they are in the media, skippers and races have a moral responsibility to be honest and transparent. It's up to the public and sponsors to judge whether ocean racing is on the right track.

Can you imagine a Paris-Dakar with 30% of the participants killing elephants and giraffes on the way? That would be inconceivable. The difference is that things are less visible at sea.

Our society is evolving, growing, and today in all areas (ecology, feminism, social), certain behaviors are no longer accepted.

In calling for transparency, we are not attacking any particular team or skipper. It's the entire ocean racing community that is collectively responsible for these collisions.

"There are plenty of whales already, one more or one less won't change the face of the world."

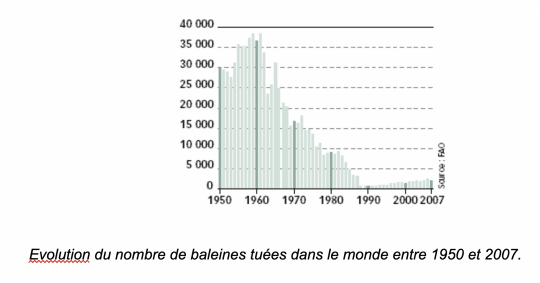

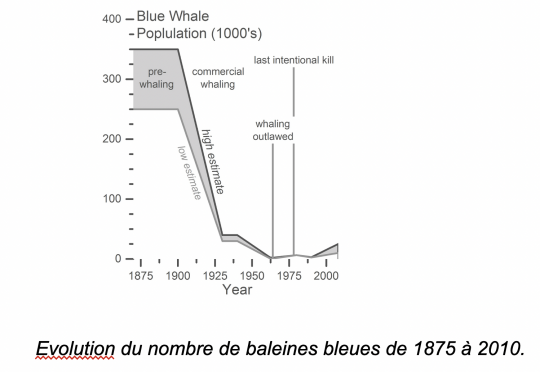

Whale populations are gradually returning to their natural levels, after being virtually eradicated by whaling in the early 20th century. The situation in the 1990s was very worrying.

Whales, some species of which are protected and whose destruction is forbidden by law, are our allies in the fight against global warming: a whale sequesters 33 tonnes of CO2 per year over its average 60-year lifespan, equivalent to 2 million tonnes of CO21. Despite being the largest marine mammal, whales are connected to microscopic plankton, and the fragile balance of the food chain cannot function without them. Whales are also highly intelligent, with advanced means of communication and transmission.

Thanks to the ecosystem services they provide, the value of a whale is estimated at 2 million dollars. While the idea of putting a value on the life and existence of a living being is questionable, it can raise awareness.

And above all, who are we to arrogate to ourselves a right of life or death over whales?

"The Arkea Ultim Challenge - Brest has set up exclusion zones in places where there are high concentrations of cetaceans"

This is a positive initiative. However, protection zones can only reduce the risk probabilistically on certain segments of the route.

The race organizers have deployed all available technological solutions to reduce collisions with marine organisms.

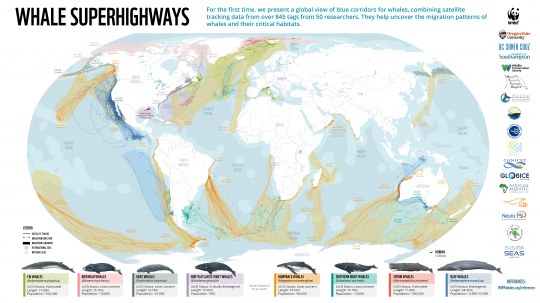

But as we can see, that's not enough. Some whales migrate up from the poles to tropical waters during the winter, so they necessarily cross race zones. There is no such thing as "whale passages" between protected areas.

On a round-the-world sail, you're bound to come across these migratory routes several times, and we're only just beginning to understand them better.

"What do you propose?"

Sailing today on these yachts, ultimate or otherwise, and at these speeds, in the habitat of cetaceans and other large marine animals, is like playing Russian roulette. It's no longer sport. The primary cause of these collisions is the race to the cult of "always more": always faster, always bigger.

The solutions are simple, for ocean racing: limiting speed, limiting the size of foils and sailboats. Public admiration forces us to be responsible, to live up to the image of courage and humility embodied by sailors. To do this, we need to put an end to the omerta, and become aware of the scale of the problem. Our sport is only a game, a form of entertainment, and does not justify harming marine animals.

We demand transparency from the racing teams, and that from now on they provide themselves with the means to systematically determine the origin of collisions.